Sometimes I wish that I could go to university without taking any classes. Although this ultimately defeats the purpose, it seems that my dedication to my coursework takes me away from the endless amount of other things I could be doing at this very institution. One of these is perusing the University of Victoria’s Special Collections.

These collections, housed in the Mearns Centre for Learning, are nothing short of phenomenal. An eclectic array of items call that basement room home. I came across the collections innocently enough while Googling UVic before classes started. What initially caught my eye was a signed photo of the “laureate of American lowlife” author Charles Bukowski, which I sent to my great friend and fellow journalist Alec Salloum back in Regina, a big fan of his.

Holding that photo and seeing the scrawl of the man whom Alec had introduced me to was existential and just so real. Staring at his physical penmanship before me was more intimate than any videos or quotes. That same hand wrote Ham on Rye.

Knowing that I had to explore more there, I journeyed to the collections to meet with Heather Dean, the Associate Dean of the Special Collections. Dean, an alumnus of this university, explained that the archives are extremely broad, consisting of rare printed material, private archives, personal papers, and more, some items even dating back to 2000 BC.

This collection, Dean highlighted, has been improved by working with the University of Victoria faculty to enrich the reservoir of material available to students (and the public): “[W]e worked with Dr. Aaron Devor, who’s in Sociology, and we have what’s believed to be the world’s largest collection of transgender archives, and that’s something we never anticipated.” Dean also pointed to the large amount of anarchist materials gathered through working with Dr. Allan Antliff, an Art History and Visual Studies professor.

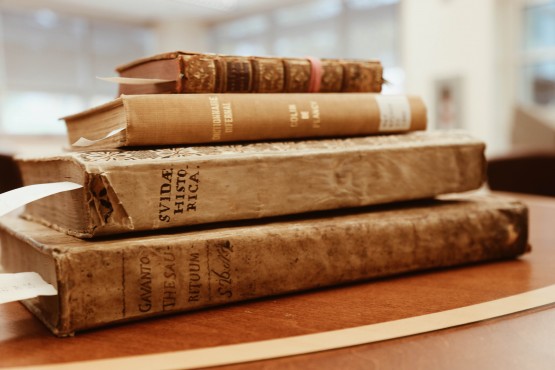

Some classes are using the resource to further experiential learning; that is, education outside of the classroom and (over-priced) textbooks. “We have a lot of classes now that come and meet in special collections, where students get to work with medieval manuscripts or they get to work with a cuneiform tablet, and they get that hands-on experience of working with an actual artefact,” Dean said. Even if your class doesn’t visit them, Dean encourages students to make use of the archives for their own assignments, which will provide an extra dimension to an essay or presentation.

More importantly though, these archives are worth visiting simply for personal intellectual nourishment. Dean generously gave me a tour, and she showed me their current W.B. Yeats display, a lawyer’s wig (what decisions were made while the judge donned that wig?), a map laying out the original architectural plan of our beautiful campus, the aforementioned cuneiform tablet, a prisoner’s armband (B2268) that Peggy Abkhazi was forced to wear under Japanese internment in Shanghai from 1943–45, and just one box out of eighty holding English author John Betjeman’s papers (a collection unmatched in the world) . . . In other words, it was a global sensory overload.

Libraries have always been a special place for me, ever since my mother took my brother and I to get books as children. This explains my reaction of fear, confusion, and pain when I first learned of book burnings at a young age — literally the fascist and medieval act of destroying knowledge. I’m glad to report that I was washed over with exactly the opposite kind of emotions during my tour. It’s no exaggeration to say that the work of archivists and librarians like Dean is the inverse of that detestable behaviour: it is immensely democratic, and offers us a deeper understanding of our existence by collecting and preserving for us elements of this world that would vanish otherwise.

Think of all the things that were never archived but lost, destroyed, or purged. Why have you yet to visit this room preserving a significant portion of the human condition?