A short history of our country’s drug control and its impacts

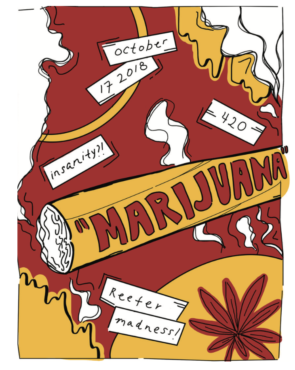

Illustration by Alyssa Savage, Graphics Contributor.

“Marihuana is that drug — a violent narcotic — an unspeakable scourge — The Real Public Enemy Number One! Its first effect is sudden violent, uncontrollable laughter; then come dangerous hallucinations — space expands, time slows down, almost stands still . . . . fixed ideas come next, conjuring up monstrous extravagances — followed by emotional disturbances, the total inability to direct thoughts, the loss of all power to resist physical emotions… leading finally to acts of shocking violence… ending often in incurable insanity.”

–Reefer Madness, 1936

Weed, ganja, pot, Mary Jane, marijuana… Cannabis goes by many names.

What many people aren’t aware of is that the various colloquial names for cannabis were shaped by racialized discourse and propaganda. Many of these words were coined in the 1900s and they’ve permeated our language and cultural understandings of the drug to this day.

“One thing that most people don’t know about the history was that Canada was a leader in drug control,” says UVic professor and drug policy researcher Susan Boyd.

“The United States didn’t federally criminalize cannabis until 1937 with the Federal Marijuana Tax Act. We criminalized cannabis in 1923.”

Boyd — who volunteered in 2016 with the federal government Task Force on Marijuana Legalization and Regulation — says that cannabis consumption in Canada was not even a common practice in the early 1900s.

“When we look at the history of cannabis criminalization, it’s quite interesting because really, in Canada, Canadians had no experience with the smoking of cannabis. They had no knowledge about the drug.”

“What we did have [were] some elixirs and tonics by the early 1900s,” says Boyd.

“Our earliest drug legislation was very race-based and white Canadians didn’t see our early drug legislation—like our Opium Act of 1908 — as directed at them.”

Cannabis and opium were not initially illegal — in fact, you didn’t even need a prescription for them. But attitudes about drugs began to change as the smoking of drugs became part of mainstream propaganda campaigns designed to racialize discourse surrounding their consumption.

“Our earliest drug legislation was very race-based and white Canadians didn’t see our early drug legislation — like our Opium Act of 1908—as directed at them,” says Boyd.

Following a race-riot in Vancouver in 1908 — which partly stemmed from white labourers and politicians discriminating against Japanese and Chinese labourers — Mackenzie King, who was the Minister of Labour at that time, was sent to B.C. to address the situation. Following his visit, King recommended the suppression of opium consumption. Canada’s first piece of drug legislation, the Opium Act, evolved as a direct response to that race-riot in 1908, says Boyd.

With very little discussion, cannabis was later added to this Act, she says.

“Cannabis had already been conflated with the ‘dangerous’ smoking of opium and cocaine and so we didn’t really differentiate between these plant-based substances.”

Looking back at newspapers from the 1920s and 1930s, there are countless headlines underlining the horrors of cannabis.

Meanwhile, politicians like Emily Murphy, the first female magistrate of Canada, wrote articles “associating these plant-based drugs with danger, criminality, harm — but also associating them with people of colour,” says Boyd.

Anti-drug educational campaigns also began popping up across Canada around the same time, and these campaigns were also racially-biased, which contributed to the exclusion of Chinese people from entering, living, or working in Canada. Looking back at newspapers from the 1920s and 1930s, there are countless headlines underlining the horrors of cannabis.

“Reefer Madness headlines associat[ed] cannabis with violence, Mexican Americans, black men in the U.S., and [portrayed] white youth [as] being vulnerable to these evil dealers and going insane or murdering people if they used cannabis,” says Boyd.

“So you can really see that in Canada, it was following the criminalization of cannabis that we really stepped up on the rhetoric about the dangers of cannabis with no evidence whatsoever.”

A headline from the Toronto Daily Star in 1938 reads: “Marijuana smoker seized with sudden craze to kill.”

One such headline from a 1938 Globe and Mail article stated : “Marijuana considered most vicious narcotic,” and goes on to claim within the article itself that marijuana is 10 times more powerful than cocaine. A similar headline from the Toronto Daily Star in the same year reads: “Marijuana smoker seized with sudden craze to kill.”

“These headlines really solidified ideas about cannabis without providing any…scientific evidence,” says Boyd. In truth, cannabis wasn’t even being used as much as headlines would suggest, she says.

“There was no epidemic at all.”

The late 1960s and early 1970s saw a major shift in North American culture and cannabis use, says Boyd.

“That’s the first time in history where cannabis use becomes popular, but what’s quite different from the past is that it was white, middle-class youths—and [the] not so youthful — who took up the smoking of cannabis.”

This surge in the prevalence of cannabis use among white youth stemmed from the counterculture movement both in and outside of Canada, and arrest records reflect the extent to which usage spiked. In 1960 there were only 21 arrests for possession of cannabis in all of Canada, while by 1972 there were over 50 000.

This shift caused quite an upset among largely middle class Canadian families. At that time, an offence involving criminalized drugs would result in life in prison.

Parents demanded change, and the federal government responded with the establishment of the Royal Commission on the Non-Medical Use of Drugs — commonly referred to as the LeDain Commission — in 1969. After conducting several studies, the LeDain Commission recommended that penalties for crimes involving cannabis be reduced.

“That was one of the first government reports that suggested that we really should repeal possession of cannabis [penalties],” says Boyd. “Later we had the Senate report in 2002 that said that we should legally regulate cannabis.”

“We don’t question that there’s a drug store on the street, we [just] assume those drugs are safe … and these drugs that are criminalized are not safe.”

When it comes to the validity of claims regarding extreme, cannabis-induced paranoia— such as those portrayed in propaganda films like Reefer Madness—“almost all research … can only prove association, not causation,” says Bridget Reidy, a family doctor who practices in Saanichton, B.C. Despite this fact, Reidy does believe that there is a need for further research into cannabis, especially when it comes to impaired driving and the effects of cannabis on mental health.

“No doubt there probably is a tendency to psychosis that can be exacerbated by [cannabis use]. That makes entire medical sense,” she says. “But did we see a spike in psychosis when marijuana became common in younger people? No.”

According to Boyd, public discourses shape our ideas about drugs.

“We don’t question that there’s a drug store on the street, we [just] assume those drugs are safe … and these drugs that are criminalized are not safe.”

“We need to look at…these arbitrary divides between legal and illegal drugs,” she says. “We should remember that cannabis…[is] an ancient plant and it was used historically for medicinal, spiritual, and recreational purposes.”

When it comes to changing the public opinion of cannabis, Boyd feels it comes down to normalizing the use of drugs.

“Canadians are a drug-consuming nation,” she says, and demonizing certain drugs over others doesn’t make us any safer.

“[We] need to pay close attention following Oct. 17 on who continues to be criminalized and whether or not it [negatively impacts] indigenous people, black people, youth, [and] cannabis activists.”

“What we need is just good information about each specific drug and that’s very hard to do when you have a drug control regime where you can’t even do necessary research.”

“Canada is the first G-7 nation to legally regulate cannabis at the federal level, and I think that’s quite important,” says Boyd.

However, she feels that we could go further and amend legislation to make the penalties more in line with the rules for tobacco and alcohol infractions.

“[We] need to pay close attention following Oct. 17 on who continues to be criminalized and whether or not it [negatively impacts] indigenous people, black people, youth, [and] cannabis activists who aren’t able to find a means into the legal market,” says Boyd.

“Those are the groups of people who — historically — have been negatively impacted by our drug control.”

Canada’s relationship with cannabis has been tumultuous. Although our opinions have certainly morphed since the 1930s, we still have a long way to go. With luck, Canada’s choice to legalize cannabis will be a step towards righting past wrongs and doing away with the Reefer Madness paranoia once and for all.