CFUV host Aldo Nazarko shares his experience at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

Provided photo by Aldo Nazarko.

There are few moments in history that are so iconic they become synonymous with their own day in the calendar.

Sept. 11, 2001 is burned into the memory of those across the world for the terrorist attacks on the Pentagon and World Trade Center in New York. May 8, 1945 is celebrated as the end of World War Two in Europe, while Nov. 9, 1989 is remembered as the day the Berlin Wall came crashing down.

Aldo Nazarko vividly remembers the day he witnessed history. It was hot, humid, and over half a century ago, but he remembers it because he was terribly dehydrated and was offered a spot on a picnic blanket in the shade.

“I was there by about 7 a.m.,” he says. His face breaks into a warm, ear-to-ear smile — the type you’d expect to see on an elegant 80-year-old storyteller. “I’m curious by nature.”

Provided photo by Aldo Nazarko.

The sweltering heat made sweat stick to his shirt, and he used a handkerchief to shield his head. Temperatures were soaring over 30 degrees Celsius, and he was standing among some 250 000 thousand civil rights supporters just steps from the Lincoln Memorial in Washington D.C.

Nazarko was travelling alone. He was in his mid-twenties in a foreign country, only years removed from immigrating to Canada as a refugee from Occupied Italy at the conclusion of WWII.

“Around eight, the busses started arriving and it was endless. It was endless,” Nazarko repeats, emphasizing the sea of people arriving at the U.S. capital to watch the now famous “I have a Dream” speech by Martin Luther King Jr.

“The first thing people getting off the busses did was set up little picnic spots and have breakfast. I was invited to join one group and they gave me a sandwich. It was fantastic.”

The day was Aug. 28, 1963, and Nazarko knew something big was brewing.

A ROADTRIP THROUGH THE PAST

Nazarko is a man with many stories to tell. Having lived eight full decades, he radiates both wisdom and a youthful exuberance that not many people his age do.

Before settling in Canada, Nazarko and his family fled the town of Rijeka (formerly known as Fiume) in present day Croatia for fears of living under a Yugoslavian-communist regime. They settled in Thunder Bay, Ontario for eight years, before moving to the west coast in 1967.

Since 2002, Nazarko has hosted a radio show called “Off the Beaten Track” on CFUV, and last August he released a book titled A River of Oranges, which chronicles his family history of immigrating to Canada after WWII.

When I first meet Nazarko, there’s something about him that reminds me of my grandpa. Maybe it’s the white tufts of hair behind his ear, the hazel-brown eyes, or the plump nose that makes me wonder if we’re related.

He wears a dark blue sweatshirt and beige khakis, just as my grandpa always would, and we walk stride for stride to a table on the main floor of the SUB.

We sit down, and Nazarko clears his throat before diving into his narrative.

“My start is four years before [MLK’s “I have a Dream speech”] in 1959. Three of us just finished high school, and we decided to go down to the Gulf for warmth.”

That summer, Nazarko and two high school friends would embark on a road trip south of the border from their hometown of Thunder Bay to the Gulf Coast of the United States, evenly splitting the hours of driving three ways.

“We drove down Highway 61 straight through, the three of us taking turns driving. That was a few years before Bryan Adams’ track Summer of 1969,” he remembers. “We drove through the entire south, just about. Starting from Missouri, Mississippi, Arkansas, Louisiana, and … we just saw the life as it was. We heard about segregation before on T.V. coverage, but to see for ourselves, this division… it was just horrible.”

In the South, the washrooms were segregated, so too were lunch counters, restaurants, and even water fountains.

“Water fountains. Oh yes, you couldn’t drink from the same water fountain. There were white and coloured… It sounds so uncivilized. Something that belongs in the 12th century maybe, but not in the 20th.”

It was on that trip that Nazarko realized the magnitude of the racial divide engulfing the United States. He admits to watching the events unfold on the news beforehand, but it’s one thing to see racial segregation on a screen versus observing it in person.

Over 50 years later, Nazarko recalls one startling example in a restaurant the trio stopped at just outside Birmingham, Alabama.

“On the way home, the three of us drove through Alabama — it was stifling hot in the middle of the afternoon. Just outside of Birmingham, we stopped at a roadside tavern for a cold beer. We entered, and it didn’t take long for us to notice that we were the only white customers,” says Nazarko.

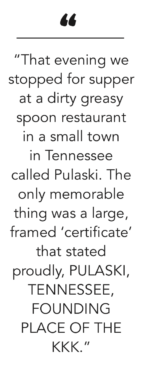

“That evening we stopped for supper at a dirty greasy spoon restaurant in a small town in Tennessee called Pulaski. The only memorable thing, aside from the awful food and the filthy washroom, was a large, framed ‘certificate’ that stated proudly, PULASKI, TENNESSEE, FOUNDING PLACE OF THE KKK.”

Once he returned home from his journey, Nazarko became fascinated with social activism. In the summer of 1963, his uncle was going to pick up his son (who had spent the summer with his aunt in Virginia) and Nazarko asked to tag along.

The duo took a bus from Toronto to Virginia, and on that overnight trip they stopped in Pennsylvania.

“We stopped … somewhere in Pennsylvania. I picked up a newspaper and it talked about the upcoming march [the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom]. I was like, ‘oh, this is a gift’, so I just told my uncle to go ahead and I stopped off in Washington.”

Nazarko smiles, and extends his hands outwards like he was flipping through that same newspaper on the summer day in 1963. The events may have happened 59 years ago, but he remembers each detail like it was yesterday.

A HISTORY OF SEGREGATION IN THE U.S.

Segregation laws in the States had been in place since the 19th century, with the first steps coming in the form of the ‘Black Codes’ — a set of restrictive laws that limited the freedom of African Americans to ensure cheap labour after the abolition of slavery.

In 1865, after wondering what to do with the some four million newly-freed slaves following the Civil War, a collection of state and municipal rules called the “Jim Crow laws” segregated everything from schools to public parks, primarily in southern states. There were separate waiting rooms for white people and black people. In 1915, Oklahoma became the first state to segregate public phone booths.

In 1865, devout white followers of the Jim Crow laws decided to form their own group to wreak havoc on the lives of black people — including vandalizing black schools and forming groups to violently hunt down black people at night. They were called the Klu Klux Klan (KKK).

During the Black Code period, the legal system was extremely biased against black people — with ex-Confederate soldiers often working as judges and police officers, ensuring minorities fell victim to harsh racial policies.

Provided photo by Aldo Nazarko.

Protests — and riots — began to occur in the wake of brutal mistreatment.

Famously, in 1955 in Montgomery, Alabama, Rosa Parks refused to give up her bus seat to a group of white passengers, and sparked a bus boycott across the city. At the same time, a little-known minister named Martin Luther King Jr. helped organize the official Montgomery Bus Boycott.

A believer in non-violent movements, King demanded that black people deserve fair treatment and courtesy, and that seating on busses should be designated on a first-come-first-serve basis.

This protest helped elevate the status of King as a national hero for civil rights, and in 1963 King helped form another powerful protest — the Birmingham Campaign. A series of lunch counter sit-ins, marches in downtown streets, and boycotts in protest of the segregation laws helped bring attention to King’s cause. The events quickly turned violent and garnered the attention of then-President John F. Kennedy.

The movement sparked Kennedy to say, “the events in Birmingham … have so increased the cries for equality that no city or state or legislate body can prudently choose to ignore them.”

The momentum was building for another protest, and later that year King would help form the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom — the stage where he delivered the “I have a Dream” speech.

Through the efforts of King and his many followers and organizers, the Civil Rights Act was signed in 1964 which slowly outlawed segregation in the U.S.

A DAY TO REMEMBER

Nazarko looks to his left, then slowly turns his head over his right shoulder and stands up. He points halfway down the SUB hallway, less than 200 meters from the table where we’re sitting at. He says that’s how close he was to Martin Luther King Jr., and countless other stars, on Aug. 28, 1963.

“All these celebrities were … involved. I was here (Nazarko points to himself in the chair) and about the distance from there (a few metres from his outstretched arm) they were all piling in. There was Marlon Brando, Burt Lancaster, Joanne Woodward — they were all there.”

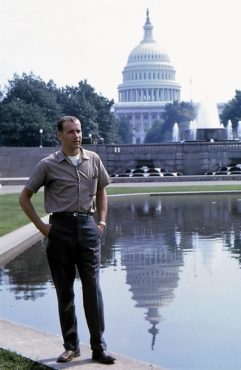

A young Nazarko stands in front of the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C. Provided photo by Aldo Nazarko.

Nazarko never thought he would become an activist, but after attending that march he found a passion for supporting causes he believed in. Since then, he’s been involved with the Occupy San Francisco movement, the ‘Walk In Her Shoes’ rally, and recently marched at the Women’s March in Victoria.

When asked what image he remembers most about the speech, Nazarko explains that the whole event was a great spectacle — not just the final speech by King, but the countless others that stood on stage beforehand.

“I think everybody realized this is something way out of the ordinary … It’s strange, they always focus on the ‘I have a Dream’ speech… but the first part of the [event] is just as fantastic as the end.”

“The other speech that made a huge impression was by the rabbi (Joachim Prinz, an immigrant from Nazi Germany, who linked his Jewish racial experience with the American African-American one). We were just in total silence listening to his speech.”

We begin to pack up from the table and go our separate ways, but I still have this nagging feeling that I’m looking at a picture-perfect image of my grandfather.

I remember being nervous while he drove me across Greater Vancouver to sports practices, but how he instantly calmed my nerves by turning down the music in his car and launching into a multi-layered story about his native homeland, Slovenia. My grandfather would always ensure I remembered my family heritage, and gave me souvenirs when he travelled back home.

I remember one Christmas when he gifted me hundreds of dollars in Croatian kuna from his latest trip to Europe. Flipping through the blue 50 kuna bills and brown 500 notes, I felt the weight in my hands drop and treasured the bills in my palms.

As I shut off my recorder and close my notebook, I tell Nazarko about how I visited Italy with my family a few years ago, and how we took a roadtrip to see my grandfather’s hometown of Bled, Slovenia.

Nazarko’s bright hazel eyes look up, and a smile slowly forms on his face.

“My mother was born in Fiume (Rijeka, Croatia), but her mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother were all born in Toplice, Slovenia (about an hour and a half drive from Bled). My family moved from Slovenia to Fiume in the 1880s.”

Nazarko is a never-ending encyclopedia of stories and facts — a walking, breathing piece of history. As we say goodbye, he pulls a souvenir from his pocket, and places it in my cupped hands. In my outstretched palm is a black and white button that reads ‘Washington March on Freedom, Aug. 28, 1963.’

The aftermath of the March on Washington. August 28, 1963. Provided photo by Aldo Nazarko.