As we come back from reading break, let’s be real: for how many students was it actually a real, stress-free “break,” and for how many was it a much-needed few days to procrastinate, panic about, and catch up on all of the assignments (not to mention sleep) that you have been meaning to get around to this semester?

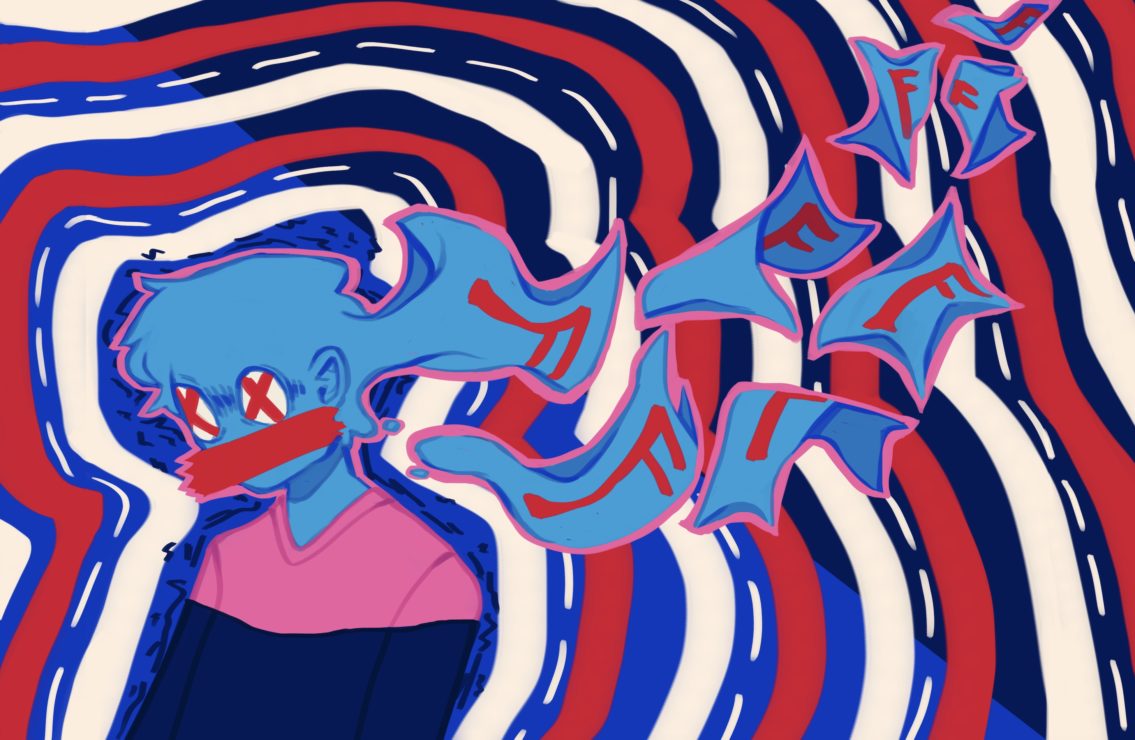

As students, it’s normal for us to joke about drowning in work and not sleeping to finish assignments. Whether it’s labs in Engineering or readings in Sociology, statistics show that the vast majority of students at UVic will feel overwhelmed at some point this semester — and we all know that the work keeps piling and piling up if you can’t keep up. This kind of consistent workload and pressure wears on students’ mental health, and students face the choice of continuing to tackle that ever-growing pile or putting their work aside to take care of their mental state.

With reading break come and gone, it seems timely to look at student mental health and how it could actually be improved. It seems to us that the operative word in the phrase “reading break” is “reading” not “break,” and we need the opposite. After all, if students are burnt out and working on their off time, is reading break really a break?

A study by the National College Health Assessment reported that 70 per cent of students at UVic reported feeling overwhelming anxiety within the last year. 90 per cent felt overwhelmed by the sheer volume of tasks they had to complete.

Although we are lucky to have excellent mental health resources on campus, like the Peer Support Centre and Counselling Services, many students are still mentally ill. While supports like this are absolutely helpful, there are still root causes of stress that they simply can’t get at.

To finish a degree “on time” (read: in four years) most students have to take five courses per semester. On paper, this can look manageable, but doing well in a university course requires significantly more time than approximately 15 hours a week sitting in a lecture hall. Professors frequently recommend that students spend three hours studying for every hour spent in class, turning students’ course load into 15 hours more per week than the minimum requirement for a full-time job.

On top of school, many students also face financial pressures. Many students have to support themselves while they get their degrees, and often have one or more jobs. Timewise, this turns what is already a full-time job into something resembling the work week of a high-powered executive, except that instead of making bank, students go into debt.

On average, Canadian students pay $4 939 a year for a bachelor’s degree — one of the highest figures among Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries. A third of the 35 OECD countries don’t charge anything for domestic tuition. The degrees in Canada also take longer to earn compared to those in some countries, adding further mental and financial strain. In the UK and Australia, a bachelor’s degree takes just three years.

On our campus and in our country, success is often correlated with your ability to work harder, longer, and later. Not having time, being too tired, or even being physically or mentally ill is not considered an excuse for poor performance.

Reading break is a much-needed breath of air, but a vast array of personal and financial circumstances mean that it’s not a breath that all of us get to take.

Some companies have been implementing programs that suggests that there may be more productivity in shortened work weeks. In a pilot study released last week, Microsoft tried out a four-day work week. Their productivity increased by 40 per cent. Last year, a firm in New Zealand implemented a four-day work week — while paying employees for five work days — with positive results.

What if success as students (and as employees) was correlated with our ability to generate creative outcomes and innovative solutions? What if we took more breaks and did less overall, but produced better quality results? The world would probably be better off.

Although some lucky (and often wealthy) students are perfectly able to cope with tight deadlines and increasing financial pressures, most of us are overwhelmed. The alarming rates of declining mental health and an overwhelming demand for mental health services at universities should be a wake up call regarding workload and balance, but instead it’s being treated with band-aid solutions.

Reading break is a much-needed breath of air, but a vast array of personal and financial circumstances mean that it’s not a breath that all of us get to take. What we really need to do is look at how much it takes out of a person to get a degree, and adjust university requirements so that students can keep up with everything expected of them. Telling students to take a break in a society that aligns breaks with failure is more than hypocritical — it’s harmful. When you’re drowning in assignments and need to pay rent, that one breath of air is not enough.