As city works to end park sheltering, aid workers and volunteers raise concerns about conditions in parks

In recent months, as shelter space has been limited by the COVID-19 pandemic and encampments in parks have grown, homelessness has become a particularly hot topic in Victoria. As winter approaches and demand for solutions increases, the city has both announced a plan to provide housing and tightened bylaw enforcement.

In October, the City of Victoria announced a plan to find shelter for 200 unhoused people living in parks by the end of 2020. On Nov. 12, city council voted to approve a plan put forward by Mayor Lisa Helps and City Councillor Jeremy Loveday to end 24/7 sheltering in parks by March 31, 2021. In the motion, Helps and Loveday expressed confidence that housing initiatives will make this possible.

In Helps’s weekly emails sent out to people who write in to the mayor and posted on her blog, Helps has outlined a bevy of initiatives intended to find housing and other supports for those experiencing homelessness.

Sixty new units of affordable housing in Langford and View Royal are expected to free up spaces in shelters, supportive housing, and in city-owned motels. Twenty-four units, managed by Our Place in View Royal, will be specifically for the unhoused community who have experienced incarceration and addiction.

The city, in partnership with BC Housing and Island Health, will be providing 110 housing supplements for those who are able to enter into the private market and free up spaces in supportive housing units. However, Helps reports that only seven private market units were available this November to people moving out of supportive housing, calling the outreach to landlords and property management companies a “massive” challenge.

There are often compounding issues facing those on the streets, such as a lack of mental health support and drug addictions, which make it difficult for them to rejoin the tough renting market in Victoria.

However, since September, Helps says that they have been able to house an additional 24 people, and that 11 more are moving out of city supports into the private market.

The city’s plan comes after the suspension of a bylaw that restricted unhoused people from maintaining their tents or temporary structures from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m., referred to as the “7-to-7 bylaw,” in light of the pandemic. The city and its citizens have since spent considerable effort shunting the unhoused community between different sites: Topaz, Pandora, Centennial Square, and lately, Beacon Hill Park and Central Park.

In 2020, the city will have spent $1.4 million managing sheltering in parks. Millions more in funding are promised by provincial and federal governments to protect and provide for some of the most vulnerable in society.

Despite the influx of promises and funding, not everyone is happy with the city’s progress. Thea Hinks, an aid worker with SOLID, a drug support and advocacy organization, who also spends much of her free time doing outreach, says that while she views the city’s housing plan as progressive and positive, she’ll believe the city’s promises when she sees action.

“There’s been no movement whatsoever,” Hinks told the Martlet. “You don’t see really any of these agencies out there plucking anybody off [the street] or doing anything.”

Beyond a lack of action on housing, Hinks is concerned about increased activity from bylaw officers.

Hinks says that in recent weeks, bylaw officers have been more active in confiscating the belongings of unhoused people. While bylaw has a mandate to remove any abandoned tents or other items, the suspension of the 7-to-7 bylaw is supposed to grant unhoused community members a degree of protection from confiscation. Hinks says that it’s obvious if a tent site has been abandoned, and that if bylaw officers are unsure whether a site is occupied, they should contact Hinks or another aid worker.

The Martlet reached out to the City of Victoria for comment, but did not receive a response by the time of publication.

For many unhoused individuals, being on the street is traumatic enough. Hinks says that unnecessary confiscations by bylaw only adds to this trauma. Additionally, due to supply chain shortages and higher demand, there are very few replacement tents and blankets available in Victoria.

“All these folks that have lost their tents have nothing,” Hinks said. “We can’t even help.”

In order to retrieve their belongings, people have to contact bylaw officers and tell them what was taken and on which day. Hinks says this is difficult for the many unhoused people who don’t have a phone and often don’t know what day of the week it is.

Another issue that Hinks says she has noticed in recent weeks is a gradual tightening of the rules and regulations on where unhoused residents of Beacon Hill can shelter. In the fall, campers in the park were moved by bylaw away from environmentally sensitive areas of the park. Since then, Hinks says that the space open to camping has increasingly dwindled.

A sign posted around the park shows the limited areas in which people are permitted to shelter. According to the city’s website, temporary shelters are not to be placed within four metres of prohibited areas such as sports fields, community gardens, footpaths, cemeteries, and boulevards. Additionally, shelters must be kept eight metres away from playgrounds and fifty metres away from school property.

“They’re so small now, these little green patches [where people can camp],” said Hinks. “They’re shading in areas where they used to be apparently allowed to camp but they’re apparently not allowed to anymore.”

Besides figuring out where they are allowed to camp and what rules they are supposed to follow while awaiting the city’s promised housing, Victoria’s unhoused community faces another problem: where to shower. With COVID-19 closures and restrictions on recreation centres and other public indoor showers, many have not had a proper shower in months. With the winter coming, having a place to get warm and clean is becoming even more important.

Our Place has showers open to the public seven days a week, but many of the unhoused are fearful of walking that far away and leaving their belongings behind. While there are showers already at Beacon Hill, there is nobody to run them as aid organizations and volunteers lack either the funds or the means to run them. Hinks says the main issue is the cost of liability insurance.

“It has to be [Victoria Cool Aid Society] or Our Place or [Portland Hotel Society], a service provider like that,” she said. “No one wants to take it on.”

Recently, a group of volunteers, including carpenter Craig Turney, built two showers for the unhoused of Beacon Hill Park. The group’s intention was to have the unhoused run the showers themselves. However, when volunteers arrived at the park to install the showers, they found the park’s water turned off, including to a hand washing station set up by the city. The city says that the group lacked the necessary permits to install the showers.

In an emailed statement to the Martlet, the City of Victoria’s Head of Engagement Bill Eisenhauer says that the city cannot allow unauthorized structures to be built, especially when they include gas-fired combustibles.

On Nov. 16, the group successfully installed the showers without permission from bylaw officers or the city. The group says that they hope the showers will remain in Beacon Hill “until a more sustainable solution is in place.” Shortly after installation, Victoria bylaw officers marked the showers for removal.

Eisenhauer also said that the city has reached out to the group several times to offer assistance and to connect them with other community service organizations, but that each time the offer has been refused.

“Since first learning about this group’s work, we have reached out several times to offer to assist with possible solutions or to help connect them with possible community service organization[s],” said Eisenhauer. “They have simply declined to work with us.”

Besides liability concerns, the city says that the provision of amenities violates the conditions of the trust that occupies the park.

Turney says that if the city is so worried about the provision of amenities, then bylaw officers should be removing other amenities already provided to the park such as needle drop boxes, hand washing stations, and garbage cans. He says that showering is, and should be, a human right.

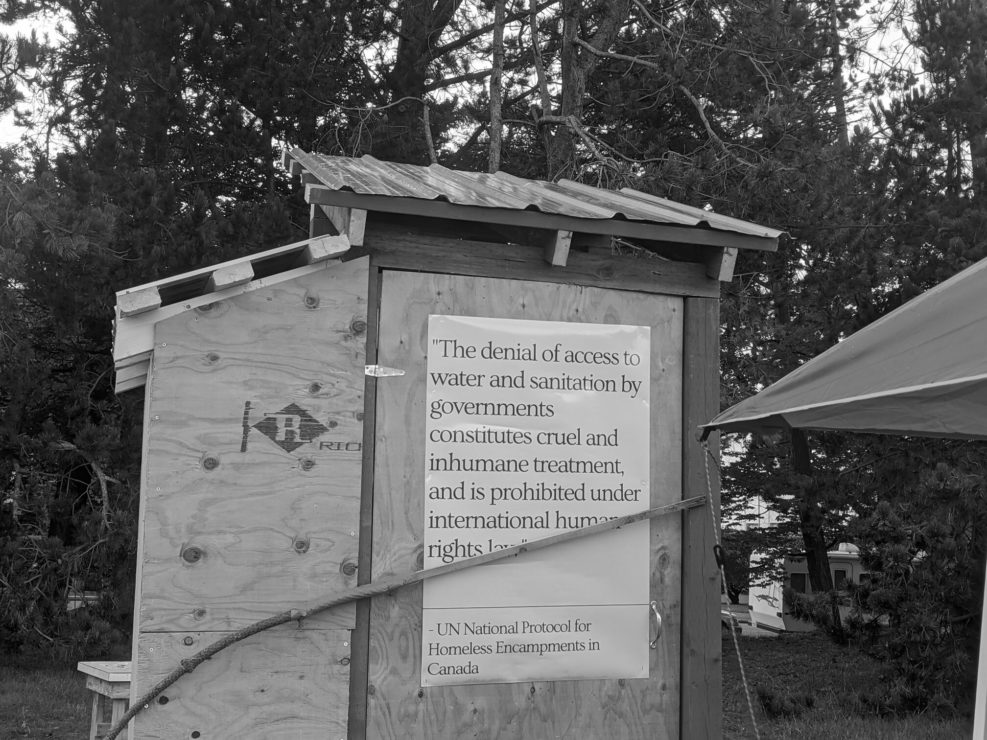

“There are higher laws, you know, like [UN National Protocol for Homeless Encampments in Canada] and basic human rights,” said Turney.

The protocol says that “the denial of access to water and sanitation by governments constitutes cruel and inhumane treatment, and is prohibited under international human rights law.”

On Nov. 20, bylaw officers, police, and a contracted demolition crew came into the park and took the Community Care Tent, which provided supplies and support to park residents, and the showers. Everything was loaded onto trucks by the demolition crew, as about 15 unhoused people and supporters looked on. One person was arrested during an altercation with police but was released shortly after.

Turney was not made aware that the showers were being impounded on Nov. 20. Shortly afterwards, Turney went to the police station to get the showers back from the impound lot. He has partnered with a local church to store them until they can find an amicable solution with the city.

Turney has been in communication with the City of Victoria alongside unhoused people and other advocates. Although they are currently applying for a grant to have the showers and care tent funded, he says the bureaucratic red tape is making it difficult to get people the support they immediately need.

“Every day that we’re going through this process is a day that people don’t have access to [basic needs],” Turney said. “To me, the emphasis is on displacement. If the city is not providing services, at the very least they can allow people to stay where they are.”

Hinks says that unless the city housing or shelters are found, Victoria’s unhoused community is in for a hard winter.

“Someone’s gonna die from exposure,” said Hinks.

Regardless of the issues currently facing Victoria’s homeless population, Hinks says that the solution is supportive housing. Whether the city’s self-imposed deadlines will be successful is another matter, but Hinks believes that housing can’t come quick enough.