Exhibition at Open Space features Indigenous artists’ relationships with land and land defence

According to Eli Hirtle, curator of the LAND BACK exhibition currently at Open Space, the chosen title is a “rallying cry.” The phrase — and the exhibition — are about putting unceded territory back into Indigenous control. The diverse installations explore this sentiment and its personal resonance. Each piece is evocative and demands time and thoughtful contemplation.

LAND BACK features work by artists Nicole Neidhardt, Lacie Burning, Chandra Melting Tallow, and Whess Harman, as well as a collaborative mural exploring the importance of this land to the Lekwungen community. The exhibition, on until mid-January, takes place on unceded Lekwungen territory at Open Space gallery in downtown Victoria.

Hirtle, who is also a multidisciplinary artist of Nêhiyaw and European descent, says activism is part of everything he does. When actions in solidarity with the Wet’suwet’en erupted in January, Hirtle was deeply affected. In 2013, he went to the Unist’ot’en camp and made a film — a pivotal experience in his life. He developed a strong connection to the place, and also realized the potential of art to ignite something deep within people. LAND BACK was sparked by the events earlier this year, but the fuel had been there for years.

Due to challenges brought on by COVID-19, there were moments when Hirtle was unsure if the exhibition could still happen. In the end, the opening was staggered throughout October and November to limit numbers. Hirtle explained that a dynamic opening had the added advantage of highlighting each artist, and also created a parallel to the ebb and flow of protests, where bodies and resources are constantly in flux.

Diné (Navajo) multidisciplinary artist Nicole Neidhardt’s installation is entitled “Beam Me Up, Asdzą́ą́ Anilí.” It’s a “Diné Transporter Pad” made of mirror mylar featuring hand-cut designs. Lately, Neidhardt has been delving into Indigenous Futurisms, which are embedded in hope, and thinking about “time travelling matriarchs and land protectors, because … we really need them right now.” Neidhardt’s installation features a portrait of her ancestor Asdzą́ą́ Anilí, who, among many other things, was an important land protector. She acts as a guide “helping other land protectors come into our temporal plane,” says Neidhardt, “but she’s also present.”

The viewer can step inside the transporter pad and onto its circular base. When they do so they become surrounded by vibrating, glittering mylar. The shimmering effect is reminiscent of the visuals used in Star Trek, according to Neidhart. The base itself is made from red earth that Neidhardt collected from her home territory and drove up to Victoria from Arizona. It was a long way to travel, but she says it was “worth it to be able to be able to presence the land in the gallery space.”

She sees the earth itself “as a time machine, because it holds so many of our stories, and our ancestors.”

Mohawk interdisciplinary artist Lacie Burning’s work features a series of photographs, and a camouflage jacket sewn shut with meticulous stitches. One image depicts a network of leaves, tree branches, and camouflage print. Camouflage is often present in land defence occupations and protests, which has prompted Burning to ask “What does the camouflage do for us? What does it do for the trees, for which it is imitating?” These questions inform and deepen the viewer’s engagement with the series and bring to mind the actual bodies involved in land defence.

According to Burning’s description, the pieces look “closely at the act of engaging with land defence tactics and desire for a future embedded in peace.” Burning grew up on Six Nations of the Grand River Reserve, not far from where an ongoing battle for land sovereignty, referred to as 1492 Land Back Lane, is taking place.

Chandra Melting Tallow is an interdisciplinary artist of mixed ancestry from the Siksika Nation. Their piece is entitled “IIKAAKIMAT,” meaning “try hard,” which they explain is an important Blackfoot sentiment. Their spiritual and surreal installation features four heads of long black hair with 216 red prayer ties in them, each one holding a specific prayer. In front of these, mouldings of Melting Tallow’s hands tenderly hold strips of red fabric. Long strands of white material adorned with bells float on either side.

“IIKAAKIMAT” also explores how people with physical disabilities can’t always participate in front-line activism and reflects on other ways to contribute. Melting Tallow recognizes their own role as creative and spiritual. They explain that it is important for them to work to “dismantle internalized ableism that is perpetuated by western society, which can undermine the different roles that people have within these kinds of movements.” They add that during the protests in February, there were many calls for prayer, which were integral to the actions, and provided an opportunity to participate.

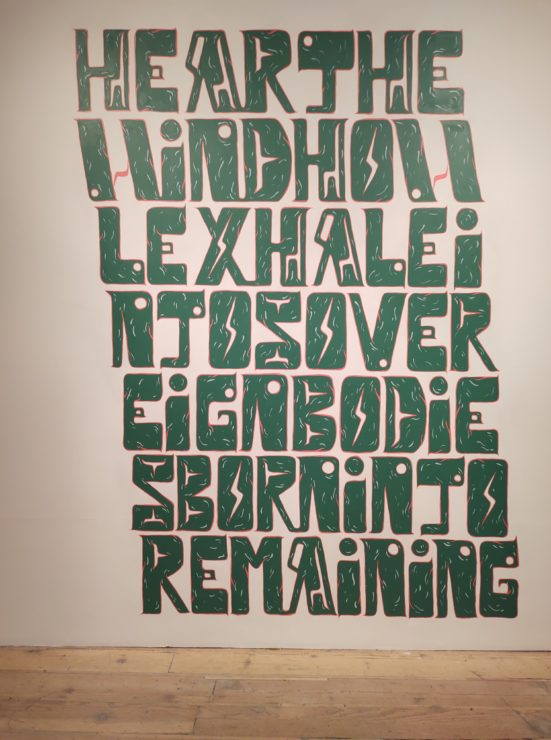

Whess Harman is a Carrier Wit’at multidisciplinary artist and curator. For the exhibition, they created a text-based installation entitled “Body as Vessel/Body as Blockade.” It’s incredibly difficult to explain the importance of their involvement with the land, Harmansays, and it’s “really emotional.” Their piece is about this untranslatable feeling.

The text uses specific forms, including Split Us, to indicate that an Indigenous person is speaking, and Harman says it “requires a certain amount of labour to read it.” They explain that’s kind of how they feel about questions regarding their connection with the land and land defence. Harman adds that they typically don’t read out the words to people. This piece requires the viewer to slow down and put in the work to understand what is being said — a sentiment that extends to the other work in this exhibition, and far beyond.

Harman’s home community is adjacent to Wet’suwet’en territory, and they explain that events in February hit hard because of the personal connection. Actively engaging in protests means facing the looming threat of violence, but for Harman it feels like the least they can do.

Harman says it can be “hard not to be cynical.” On their birthday this year, they watched friends getting arrested and held hostage for hours. Nevertheless, they do feel hopeful when they’re at protests, mostly because of the deep connection shared with other protesters.

“It’s a more interesting story to be hopeful than to be totally crushed down and demoralized by something,” says Harman.

The Lekwungen Youth “Unity” mural featured in the exhibition was created by five Lekwungen youth, Neidhardt, and Brianna Bear, a community knowledge keeper and artist from the Songhees/Lekwungen Nation. Due to COVID-19, the mural making process had to be adapted. Care packages, including art supplies, were sent out to Lekwungen youth, and Neidhardt and Bear incorporated the contributed designs into the final mural. The mural depicts the place where “the underwater world meets the surface,” says Neidhardt.

A film by Bear and Hirtle, Lekwungen: Place to Smoke Herring, also plays as visitors ascend the stairs to enter the exhibit, reminding them where they are: Lekwungen territory. Hirtle notes that it’s incredibly important to ground the exhibition on the land where it takes place.

LAND BACK leaves the viewer with a lot to think about.

“All the works in the gallery … contain sorrow,” says Hirtle, “… but they also contain strength and hope.”

He adds that art can be rejuvenating, and it’s an important part of resistance, because “it can create a dialogue outside of the mainstream.” Among other things, this exhibition allows space to imagine better futures.

LAND BACK is at Open Space until Jan. 16, 2021, and can also be viewed online.