U.S. Supreme Court ruled AWF liable for copyright infringement, sparking debate about commercialism vs. creation

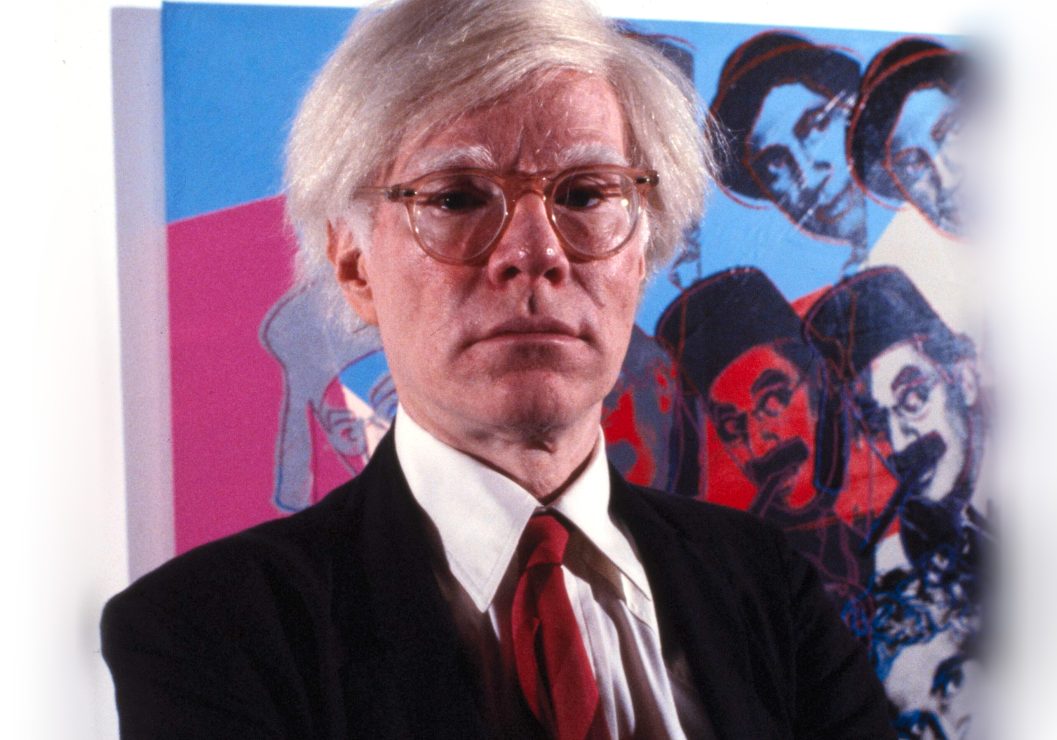

Photo by Bernard Gotfryd.

On May 18, 2023, the U.S. Supreme Court delivered a landmark ruling against the Andy Warhol Foundation (AWF) in a copyright case brought by photographer Lynn Goldsmith. The court ruled 7 to 2 in Goldsmith’s favour, adding in their summary, “Original works, like those of other photographers, are entitled to copyright protection, even against famous artists.”

This may feel like a triumphant win in a David and Goliath battle: a progressive rock‘n’roll photographer takes on a 20th-century titan and wins. However, it has sparked debate among critics and commentators on whether this ruling could have wide-ranging repercussions for creative development.

The case addressed a licensing issue made in 2016 by the AWF, who sold rights for Warhol’s “Orange Prince” to Conde Nast Publications. Warhol, who passed away in 1987, created the silk screen as part of a series of portraits based on a 1981 photographic portrait by Goldsmith. Goldsmith initially permitted use of her image, which Warhol adapted for Vanity Fair magazine in 1984. Yet, the photographer alleged that she only became aware Warhol had also produced other prints using her photo when Vanity Fair put “Orange Prince” on the cover.

Nobody denied that Warhol used Goldsmith’s photograph — that is obvious when one puts the two images side by side. Rather, at the core of this debate is the Fair Use doctrine. This doctrine allows the licensing of copyright material for limited purposes such as parody, criticism, or commentary. Fair Use enables us to watch movies or television clips in the classroom, read book extracts and quotations in reviews, or even enjoy YouTube commentators that make use of other creators’ copyright material.

Warhol’s lawyers argued that Warhol’s work was “transformative,” infusing the image with a new meaning or message. Goldsmith captured a young singer on the precipice of international stardom, which she would later refer to as a “portrait of vulnerability.” On the other hand, the foundation says, Warhol’s image is cropped and coloured, with a “flat, impersonal, disembodied, mask-like appearance.”

The court that ruled against the AWF seemed to prioritize the commercial purposes of the work over this interpretation. The AWF sold their image as an illustration for a magazine, directly competing in the marketplace of music photographers such as Goldsmith. The court’s decision said that because both images were used to illustrate special editions dedicated to Prince, they serve “substantially the same purpose.”

However, from an artistic lens, you could argue differently. If Vanity Fair wanted to profile Prince with a candid, inscrutable Goldsmith photograph as their illustration, they could have approached Goldsmith directly. However, the choice of a bold, graphic Warhol print sends a different message about the tribulations and dehumanizing nature of fame-obsessed culture.

Recently, another case made it to federal court in New York that demonstrates the need to allow adaptation and re-use in creative work. British singer-songwriter Ed Sheeran emerged triumphant when Marvin Gaye’s estate holders accused him of copying the soul classic “Let’s Get It On” in the 2014 ballad, “Thinking Out Loud.”

Sheeran played his guitar in front of the court, to demonstrate how common the four-chord progression was. Sheeran’s lawyer, Irene Farkas argued that “no one owns basic musical building blocks.” If artists could monopolize these elements, many of the hits we know today may not exist.

This points to a broader problem with the Goldsmith ruling. Art does not exist in a vacuum and many artists rely or draw upon what has come before to create their work. New York Times critic Adam Liptak, discussing the case on The Daily podcast said, “It’s important to create some space for artists to make use of earlier works.”

Appropriation art, which samples existing images, products, and materials to create art, is a part of a modernist tradition that raises questions about how we define art itself. It’s a part of the tradition that artists as respected as Georges Braque or Salvador Dali made use of.

Resource-rich foundations like the AWF and famous singers like Sheeran may have the means to go to bat on issues like this. However, a ruling against fair use could leave less financially successful artists open to litigation; even make them fearful of creation in the first place.

Justice Elena Kagan, writing the dissent alongside Justice John Roberts, said that the results of the case “will impede new art and music and literature. It will thwart the expression of new ideas and the attainment of new knowledge. It will make our world poorer.” Kagan and Roberts’ statements may seem hyperbolic, but the sentiment remains that this could have knock-on effects in other cases. How this ruling may affect future interpretations of the law and filter down through lower courts remains to be seen.