A Climate Disaster Project feature series

The stories in this series were shared as part of the Climate Disaster Project (CDP), an international collaboration of post-secondary and media partners coordinated through UVic’s writing department. Students in CDP classes learn trauma-informed techniques for interviewing and working with survivors of disasters from wildfires to floods to extreme heat. Before they take that work into the community, these students interview each other, sharing their own experiences with climate change and what they think they can be done about it. These are some of their stories.

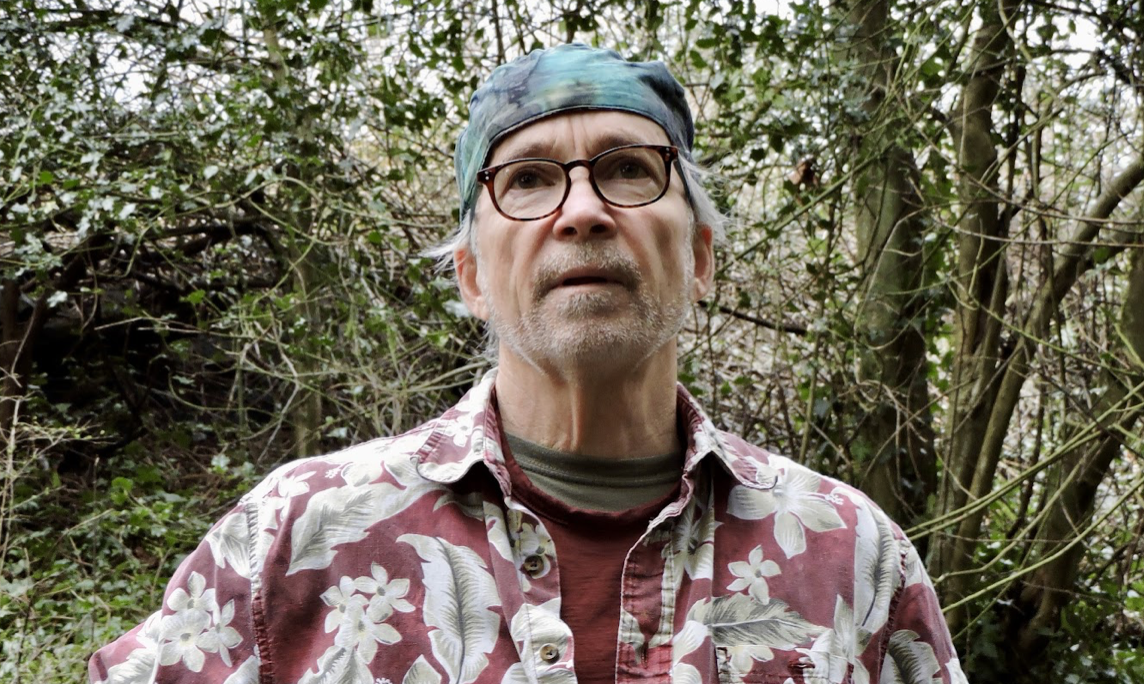

Paul Monfette, photo by Naomi Duska

Victoria, Canada, Pacific Northwest Wildfires

Growing up in the 1960s, Paul spent time in Toronto and on their uncle’s farm in Quebec. There, they climbed trees, got to know the pigs and chickens and the surrounding wilds. ‘I’ll always remember lying on a cow when I was sick one time. It was wonderful,’ says Paul, describing nature as ‘one of the saving graces for me.’ Paul just completed their bachelors degree in writing at the University of Victoria. They were recently involved in the Fairy Creek blockades, protesting the logging of old growth forests.

My first experience of the degradation of man towards nature was as a tree planter back circa 1980 to 85. At times, it would feel like I was being sucked into the earth by the spirits of the killed trees, that often were left lying strewn about, like a bunch of corpses, and then bulldozed into piles to be burned. It was like Mordor you know. It was the dark lord. And then I would plant to the edge of the clear cut and wander into the old growth. And the night and day experience was so profound, just wandering one hundred feet into the mossy, damp, lush world that was there.

Then, the first year of the fires: the smoke was every day, for a long time. The sun on the Island was obscured. I drove to the Kootenays to do a retreat. And I heard people with respiratory problems really struggling. The smoke was so thick, it was hard to breathe. It felt once again, like it was apocalyptic. There was the sense of doom. And I was like, okay, this is real.

Some in my community take strong action and are inspiring for me. I take some strong action myself and hopefully inspire others. I think that’s the way it works. We’re on fire. And people catch fire from your fire.

I have a friend who’s a super activist. She’s one of the first organizers of Fairy Creek. She’s also a theatre person. And she said, ‘Okay, I know you’re nervous.’ I had been involved in logging blockades before. People’s trauma gets stirred up. It gets reactivated. So it’s challenging. I tend to want to not be so front and centre. But she knew she’d get me involved if we co-created a play to perform in front of a rally. So I got to play John Horgan. Another guy had a real chainsaw going without a chain, and we were cutting down the trees in front of City Hall. It looked real because we had sawdust, and the two chainsaws running. I’m playing Horgan who’s doing a dance, cheering on the trees being cut down.

Then there was a march to take place, blocking the street. We were walking down blocking all the traffic. I was handed the bullhorn by someone because he thought I looked like a good person, fairly respectable. It’d be good PR to have me leading the march. So there I go from being nervous about my too over-involvement, to leading the march, kind of walking back and forth.

With the chants going, ‘Hey, hey, ho, ho, John Horgan’s got to go,’ I’m just totally over the waterfall. And it was completely fine. I was worried I’d probably be on the news because I’m friends with people who are like, ‘Why would you want to be with the extreme fringe?’ At that point I kind of radicalized myself more, and then started not caring. You know, if you want to unfriend me, unfriend me. I don’t care.

Here’s what’s important to me. I’m going to post about Fairy Creek and whatever on Facebook and try and get people involved. And I might have lost some friends over that. I need to be the voice for those that cannot stand for themselves, like the trees and the lichen, and all of the animals. They don’t have a voice. Because, you know, when I was a kid, I kind of promised the animals that I would look after them.

It’s almost like the people are holding your breath, and closing your eyes and saying, ‘There’s no climate change, there’s no climate change.’ To have a forum and a format, somewhat, to talk about it, to say how I’m being affected, to be emotional, to cry is to be empowered.

We might be powerless. At least when you’re being frontline activists, you’re actually taking matters into your own hands. You’re taking action. Your conscience becomes free. And that’s what’s important. Things might not change. But to do something, to take action, is to be free from victimhood.