Before modern AI technology, ancient philosophers mythologized about creating intelligent life

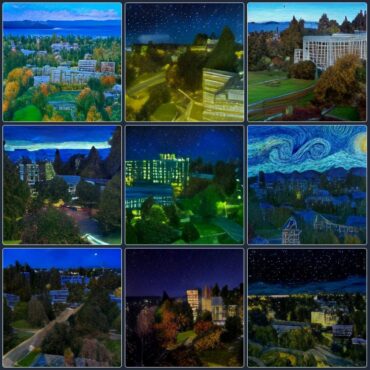

Computer-generated art from the sentence “University of Victoria from above in the style of Picasso’s Starry Night” (DALL-E), provided by Jonas Buro.

Since the dawn of antiquity, humankind has pondered on creating intelligent life. We are captivated by the idea that we could bring into the world an artificial intelligence that surpasses our own.

The holy grail of modern computer science research is to invent such an entity, known as artificial general intelligence. Computer scientists speculate that this critical moment of creation, known in the literature as the singularity, would create a positive feedback loop in which the entity rapidly improves itself. If kept under human control, this creation has the potential to be the last invention we ever need to make, potentially ushering in a new age of prosperity for our species. Sundar Pichai, CEO of Google, speculates that this would fundamentally alter the human experience more so than fire or electricity.

But, is this AI utopia even attainable, or is it just wishful thinking by a creature with an inflated God complex? How did we even come to imagine AI in this way?

The thinkers of old — although lacking in the means to formalize — let alone build such intelligence, philosophized about creation at great length. In ancient Greece, myths were told which describe such AIs. At the time, these stories fell purely into the realm of absurdity, but in our day and age are increasingly within reach.

For instance, Daedalus, a mythical Greek inventor and architect, crafted living bronze sculptures which exhibited human-like behaviour and emotions. These so-called automatons, which had minds of their own, were the subject of debate by Greek scholars. Similarly to some modern artificial intelligence ethicists, they stressed that such robots must always remain under human control, lest they band together and revolt against us.

Aristotle, the first to formulate laws governing the rational part of the mind, also showed an interest in these machines. He speculated in Politics that the only condition that would rid the world of slavery is the introduction of intelligent automata which relieve humanity of tedious work.

Many other civilizations, such as the ancient Egyptians, had their own stories and ideas about automatons. These olden myths and their analyses staked out concepts surrounding artificial intelligence, planting the seed of AI in the mind of man long ago, but it wasn’t until much later that humanity developed the tools and methods of reasoning which might allow it to sprout.

Armed with concepts from mathematics and the first programmable digital computers, the field of modern AI research was born in Dartmouth in the 1950s.

U.S. researchers interested in the study of intelligence congregated for a much anticipated two-month workshop, laying the foundations for perhaps humanity’s greatest vision. Building on the conjecture that “every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can be in principle so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it,” John McCarthy invited a diverse group of cutting edge research scientists spanning fields such as complexity theory, neural networks, learning machines, and computational science to partake in an event which would radically impact the entire scientific community.

This gathering, among other things, hoped to address the implications of a fascinating trend; evidence was starting to mount that computing power was doubling about every two years, a phenomenon later coined as Moore’s Law. This trend was what computer scientists had been waiting for: computational hardware power had begun its rapid ascent, promising greater access to faster computational resources for their many algorithms and ideas. Finally, the opportunity had come to put to the test the many theories which had accumulated over the centuries.

Although visionary and influential, the conference did not deliver immediate game-changing results. The stars hadn’t yet aligned; computing power was still very much in its infancy, with CPUs clocking in on the megahertz scale and having less memory available than the equivalent of a modern text document.

It would take several plagued decades wrought with over-promising, under-delivering, funding droughts, and fundamental shifts in approach to transform the budding research area into what it is today — a multi-billion dollar endeavour.

Although we still have yet to create a general artificial intelligence, we have made incredible leaps forward in narrow artificial intelligence. The goal of narrow AI is to complete a single or small group of tasks which require some degree of intelligence, such as language translation or image recognition.

These narrow AIs are embedded within our society at every level, from healthcare applications, to recommendation systems on social media, to national defence. The world as we know it is being shaped by this accelerating technology. The increasing computational power and availability of digital information in this age of big data has allowed one particular model, the artificial neural network, to flourish. Loosely based on the synaptic connections in our brains, these networks allow computers to recognize patterns and solve problems.

It remains to be seen whether these models are sufficient to take AI to the next level, or if a new innovation will pave the way. Either way, computer scientists, such as those at Canada’s national AI institutes, are continuing to strive for what we have always pondered — can we create artificial life?