Three individuals are telling the stories of Victoria’s street community, as well as their own, in a mutual healing process

It’s 2006. Documentary filmmaker Krista Loughton sits in a coffee shop across from a Victoria drop-in centre. She is there to document the lives of four members of Victoria’s homeless community. She doesn’t realize yet that this attempt to portray the effects of poverty, trauma, and drug addiction will become a personal journey. When the documentary is released in 2015, Loughton will have formed lifelong friendships and discovered some of the roots of her own trauma through the project.

Fast forward to 2017. Another filmmaker, Cory Resilient, is moving from shelter to shelter across southern Vancouver Island. Some nights he is fortunate and finds a bed or a mat on a gymnasium floor. Other nights he ends up on a park bench.* In an attempt to break the stigma he faces on a regular basis, Resilience begins documenting his daily tribulations.

Let’s take one more jump in time to fall 2020. Amidst a global pandemic, Ross Turchyn is living under a tree in Beacon Hill Park, 20 feet away from a decoy tent he set up in response to incidents of abuse and robbery. Instead of getting discouraged about his circumstances, the Canadian Armed Forces veteran and psychology graduate is in the process of starting a YouTube channel and a website to document the lives of those living in the park.

This is the story of three individuals. Each from different backgrounds. Each with different life experiences. Despite their differences, they are connected through their determination to to document the voices of people who are often marginalized, and through the healing this process has brought each of them.

Loughton, Resilient, and Turchyn spoke to the Martlet about their work, lives, and hopes for the future. As homelessness becomes an increasingly polarized issue, the filmmakers are among the few highlighting the voices of the unhoused.

Recovery through friendship

Ever since she can remember, Loughton wanted to help. Born in Brandon, Manitoba, Loughton visited Harare, Zimbabwe at the age of 19, where her father worked for a social development agency. The poverty she witnessed made a lasting impression.

“I went from small-town Manitoba to a country where [a majority] of the population were sleeping on dirt floors and bare ground,” Loughton says. “I couldn’t get over that.”

Since then, Loughton hoped to help alleviate poverty and initially planned to return to Africa. Eventually, after moving to the West Coast and seeing the homelessness crisis, Loughton saw her opportunity.

“I moved out to the West Coast and realized, you know, I don’t need to go back to Africa to help people, all I need to do is go downtown,” says Loughton.

In 2006, Loughton heard about Our Place, a local drop-in centre which provides free showers, meals, clothing, counselling and outreach services. Loughton went down to check out the centre and see how she could help.

Over time she met four regulars to the drop-in centre: Stan Hunter, Karen Montgrand, Eddie Golko, and Dawnellda Gauthier. Hunter, Montgrand, Golko, and Gauthier all had spent decades on the street due to trauma and mental illness. All had turned to drugs or alcohol as coping mechanisms and become addicted.

Hunter, Gauthier, and Golko all were able to get housing in the new Our Place facility while Montgrand remained on the street bouncing from shelter to shelter.

Loughton began documenting their daily lives in 2008 — after two years a close bond had formed between Loughton, Hunter, Montgrand, Golko, and Gauthier. The documentary of her and her four friends was titled “Us and Them” and was released in December 2015. Since then, Loughton has toured promoting her film and advocating solutions for homelessness.

The Indigenous teachings of the Medicine Wheel play a key part in the film. After receiving permission from Chief Phil Lane Jr. of the Dakota and Chickasaw Nations, Loughton borrowed the techniques of the Medicine Wheel in an attempt to help the others with the trauma of their past.

Loughton had been introduced to the wheel years earlier by an Indigenous woman who gave her a copy of a book on the topic. Although she was aware of her non-Indigenous roots and was hesitant to borrow from another culture, Lane’s blessing gave her the strength to move forward with something that she felt worked.

Loughton says that if she were making this film in 2020 instead of 2008, she would not have used the medicine wheel in her documentary because of the current political climate and her own recognition of her non-Indigenous roots. Despite this, Loughton says she has voiced these concerns to Indigenous elders who said that her use of the medicine wheel was done respectfully and for the right reasons.

Over the next year, Loughton documented the group’s recovery process using the medicine wheel and their friendship.

Through a collective effort, the group began improving. Hunter got clean and acquired a job as a taxi driver. Gauthier worked on getting well enough to see her children. Golko aimed to get off methadone. Montgrand made a concerted effort to quit drinking.

In November 2009, Hunter passed away from pancreatic cancer. Afterwards, the healing process for the other three stalled. Loughton sought the advice of childhood and development trauma specialist Dr. Gabor Maté to see how she could better help her friends. Unexpectedly, she also gained a deeper understanding of her own trauma and drive.

As an infant, Loughton’s mom was ill and her dad was always working. At the age of three, her parents divorced. Since childhood, Loughton felt an inexplicable sadness, but helping other people made it feel productive. Through talking to Maté, Loughton learned that in order to help others she also needs to help herself.

Over the following years, Loughton continued to support Montgrand, Gauthier, and Golko with this new mindset.

Golko is still working to get off methadone but has reconnected with family and is stably housed. Montgrand got sober in 2015 with help from Chief Phil Lane Jr., and has been given her own Indigenous name, which means “walks in the wind woman” and found stable housing. Montgrand is now stably housed as well. Gauthier died in 2011, but Loughton says although Gauthier’s death made her sad, their friendship made her a stronger person.

As for Loughton, she says that she is still working on her own healing and that her journey isn’t yet complete.

“We make friends with our depression,” she says. “I respect it.”

She remains in contact with Golko and Montgrand, who are still continuing with their own journeys to recovery.

Recovery through resilience

Resilient is more than an alias for Cory Resilient — it’s a summary of his life to this point.

Resilient was born in Ontario. In his childhood, Resilient’s mother and step dad would fight with each other and sometimes assault Resilient. At school, he was always tired because his parent’s arguments would keep him awake at night. His anger towards his parents would often manifest in violent outbursts against classmates.

When he was a teenager, Resilient ran away to live with his dad, who had gotten out of prison after serving a 10-year sentence for armed robbery. His dad initially was a breath of fresh air and took care of Resilient. He made sure Resilient did his school work, got to bed on time, and did all the other things a dad is supposed to do.

Eventually, however, Resilient’s dad fell back into old patterns of crime and drug addiction. After his wife left him, Resilient’s dad set up their apartment as a crack cocaine lab and had Resilient facilitate deliveries and pickups. Resilient says he was taught to use a gun, both to protect himself, and to threaten drug dealers. This life impacted Resilient significantly — he gained a juvenile detention record, fell behind in his education, and began to forget there were other ways of living.

When Resilient was 15, his dad went to jail for three years and Resilient was forced to fend for himself. At 18, Resilient himself was arrested and imprisoned. While he was in jail, his dad was admitted to the ICU with pneumonia and died without Resilient being able to see him.

Now on his own, Resilient found himself homeless. After seeing the effects of drugs and alcohol on his parents and friends, Resilient swore to not use substance use as a coping mechanism. Despite this, he found getting a job difficult.

“I found out pretty quickly how hard it was to try to get a job when you have a criminal record,” Resilient says. “Society looks at you differently.”

Unfortunately, childhood trauma caught up to him. Devastation and depression were affecting his daily functioning and eventually he was fired from his job. After being able to afford an apartment for a bit, Resilient was back on the street.*

Eventually, he moved to the West Coast, hoping for a fresh start. Resilient says he spent time moving from shelter to shelter, and even spent time living in Beacon Hill Park.

In 2017, Resilient started a YouTube channel to document his experience living on the street. He hoped that a first-hand point of view would help reduce the stigma around homelessness and show his struggles. Resilient says that he wanted to show people the systems that kept him down.

“[People say] ‘you think the world’s out to get you,’” says Resilient. “But when you grow up like that, and you realize that you’re at a disadvantage, the world really is against you.”

In 2019, Resilient was able to secure a room at Anawim House, which provides supportive housing for those who are not using drugs or alcohol and need to work through trauma. He has lived there for a year now and is focusing on recovery and supporting others. He has a job with the Experience Project, which documents the lives of those living on the street, as a program developer and speaker. He also eventually hopes to transition out of assisted housing and into a place he can call his own.

But for now it is all about continuing to be resilient and showing others that there is a way out.

“I’m not going to be defeated by this system, or society, or this view, or the stigma, and I’m going to be resilient, and I’m going to defeat the system,” says Resilient. “I’m going to overcome homelessness, and then I’m going to stand in the face of society and the system and tell them the truth.”

Recovery through strength

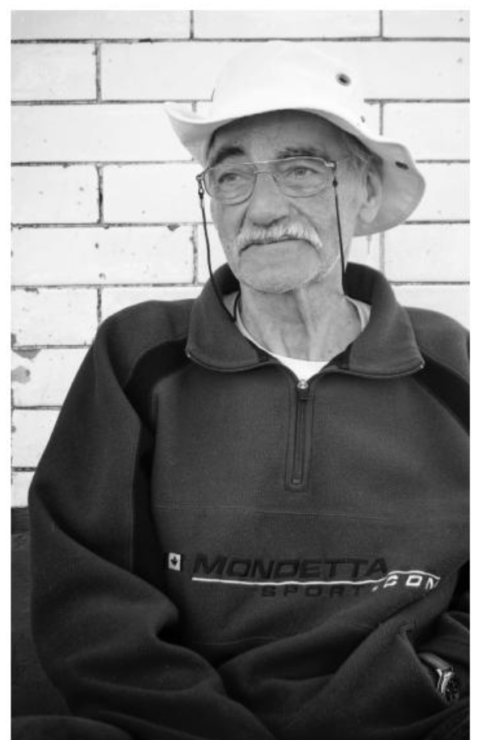

Ross Turchyn seems like an old uncle who would like nothing more than to explain his favourite book to you. He is affable and quick to laugh. He also says “totally” at the end of every sentence, like a Californian surfer. Turchyn is also homeless.

The veteran lives in a camouflaged tent in Beacon Hill Park not too far from the Children’s Farm. He has set up a decoy tent nearby to distract from his real tent in response to instances of robbery and abuse. He stocks the decoy tent with sleeping bags and blankets for those who need them.

Turchyn was born with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. Additionally, his abusive parents raised him to be a soldier which has left him dealing with residual trauma. During his time in the military, where he served as a reconnaissance soldier, he often confronted dangerous and traumatic situations.

After leaving the military, Turchyn went tree-planting, and estimates he planted around 560 000 trees over many years. Despite holding a degree in psychology, Turchyn’s disability leaves him unable to work. He has been on disability insurance for over 30 years, which he says gives him between $300-375 per month. In a city like Victoria, this barely covers the cost of food, never mind rent.

“Because you’re disabled, your life is a guarantee of pain,” says Turchyn.

However, he’s not letting his disability darken his outlook on life. He is looking to turn weakness into strength by training for his 2030 Olympic Games dreams where he wants to show the world what a disabled person can do.

Before that, however, Turchyn hopes to document what is happening around him in Beacon Hill Park. He says he plans to launch his own website and YouTube channel where he will document his life and those of his 135 or so neighbours.

“What’s going on in this park is a slideshow of what’s happening in Canada,” Turchyn said. “We’ve taken our tax cuts without pay raises for 30 years now, and this is the result.”

He says that he would like to have students get involved with his project and help him create a multimedia approach to storytelling.

Turchyn says he also hopes to create opportunities for some of his neighbours to get housing by setting up a GoFundMe page to hopefully get some of his friends off the streets.

For now though, he’s just focused on getting his website up and running, and on his Olympic training.

“For Canada, the biggest limitation of our ‘culture of the capable’ is understanding weakness.” Turchyn says. “I’m turning the tables on all that.”

Next steps

Through documenting their lives as well the lives of others dealing with trauma, tragedy, and homelessness, Loughton, Resilient, and Turchyn are some of the few members of the Victoria community providing a platform for those who so often are left without one. The documenting process has also served as a means of recovery for all of them. However, when they consider the bigger picture of their work, all three emphasize the need for wider change.

Loughton sees homelessness as stemming from colonization, trauma, disinvestment in social housing, deinstitutionalization of mental health facilities, and addiction. She says all of these must be addressed to solve homelessness.

“They go together, they’re one in the same,” says Loughton. “All the different systems that have created this aren’t working well enough.”

Loughton’s next film, tentatively titled “Home,” highlights these causes and advocates for a policy response. She also notes that colonization is particularly important to address since Indigenous people are so disproportionately affected by homelessness.

Loughton will also be showing virtual screenings of “Us and Them” between World Homeless Day on Oct. 10 to National Housing Day on Nov. 22 to draw attention to the continued prevalence of homelessness in Canada.

Resilient also sees homelessness as a societal issue. He says he’d like to see diversified supports and levels of social housing as well as a shift in public perception of homelessness.

“People can’t see why people cannot get out of homelessness,” he says. “They just blame it on the individual when they need to take a look at the system itself. And they need to take a look at the attitude of society.”

Resilient continues to document his daily experiences on his Youtube channel. Meanwhile, his website promotes his self-made documentary (available on his Youtube channel) as well as his upcoming film with VicNews which aims to show the human side of homelessness. Resilient is also continuing to work with the Existence Project as a speaker.

Lastly, Turchyn sees dehumanization as the fundamental problem..

“What we’re fighting … is dehumanization,” Turchyn says. “Human decency is just an equivalent social response, that’s all.”

Neither Turchyn’s GoFundMe page or website are up and running yet but he says he hopes to have everything ready before the end of the year. He is working with several other community members on the project and hopes to get more people involved.

However different they find the root causes of homelessness, Loughton, Resilient, and Turchyn say that they will continue to document the experiences of those living on the street in the hopes of fostering change.

*A previous version of this article stated that Resilient had one job, which allowed him to afford an apartment. Resilient has had multiple jobs. Another sentence indicated that he has slept in storefronts. This was incorrect.

These sentences have been corrected and we sincerely regret these errors.