Two groups of aspiring photographers really rile me up: the overly technical and the technophobic. The overly technical photographer knows all the settings and will argue endlessly about the benefits of 14-bit RAW capture or why brand A is better than brand B, but their images remain uninspired. The technophobe wants to make beautiful pictures, but they don’t care about the nuts and bolts. They might think that settings are just something that gets in the way of the creative process, and that people who care so much about metadata are just “measurebators” who forget the cardinal rule: it’s not the camera, it’s the photographer. These seemingly opposing camps have one thing in common, though: a fundamental misunderstanding about why technical knowledge is useful.

When I first started taking photos in Grade 11, I had a very technical approach. I quickly learned the relationship between shutter speed, aperture and ISO, how to trigger remote flashes and how to set the camera to all the different modes. I was brimming with facts, but in a whole year, I shot only one photo that I was proud of. It took me a while, but I finally realized I was trying to ace an English class by memorizing the dictionary instead of using the words I knew to craft a story.

Let me put this in the context of ISO. I knew that to keep digital noise (grain) under control, I should keep my ISO as low as possible, but a grain-free image isn’t necessarily a good one. In this shot, I deliberately kept my ISO at 800 in an attempt to lower noise, but I couldn’t freeze the action in front of me without using the pop-up flash. I was so bent on suppressing grain that I wasn’t paying attention to the scene in my viewfinder. The quality of light and capturing the decisive moment became secondary endeavours, and that should never be the case.

When I cover events now, particularly in restaurants and theatres, I prefer to use available light, so I have to embrace the grain that comes with uncomfortably high ISO settings. On the night of the 2012 US presidential election, I was wandering Felicita’s with a fast f/1.8 lens and my D300 set to ISO 3200. I used the light coming from television screens, cell phones and overhead pot lights to light my images, and though they’re quite grainy, they’re at least true to life. Of course I had to know what settings would work to make the images I wanted, but I didn’t let the dials and switches overwhelm me.

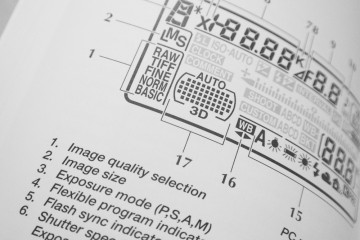

Dark clubs and theatres might test your knowledge of ISO, but when shooting sports, a deep understanding of how autofocus works is a great advantage. A strong sense of timing and composition is crucial, but if you forget to set your camera to track a moving player or if you’re unaware of what the optimal Dynamic AF setting is for sports (it’s 21-point dynamic for Nikon, by the way), that perfect punt will be out of focus. The technical deficiency would overwhelm the decisive moment. If your tool of expression befuddles you, how can you speak clearly?

Digital sensors can make practically noise-free images in the most challenging environments, but the conversations among photographers are as noisy as ever. The modern photographer has to keep up with technology like never before, and it’s easy to forget to contextualize the technical stuff. If you’re getting the results you crave without knowing a lick about apertures, great, but once you figure out that arcane menu setting or buy your first cheap f/1.8 lens, your horizons, like your aperture, can widen.