Continued from the main story.

Despite the fear in the back of voters’ minds, optimism was evident. Three parties: National, Liberal and Libre took part in the primaries. This was the first time the country had moved away from their (mostly) bi-partisan system, traditionally involving the Liberal and National Parties. Around seven parties will take part in the election next November (that figure includes smaller parties not allowed to participate in the primary elections). The inclusion of Libre in the primaries is a major step in legitimizing the peaceful intention of the resistance movement.

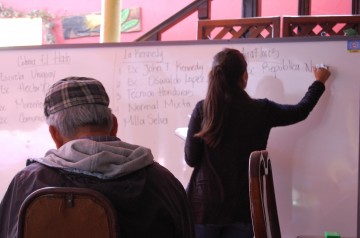

We got to the polls in Tegucigalpa on Nov. 18 in our blue t-shirts with Observadora Internationale Derechos de Humanos (International Human Rights Observer) in white text on the front. We had ID cards on lanyards from COFADEH, the coalition for the families of the disappeared, to identify and connect us to a local, respected organization. The polls opened early, and our delegation split into groups of three and arrived at our assigned voting stations around 7:30 a.m. My group went to Escuela Republica Nicaragua first. It was a small, one-storey building in a compound surrounded by a wall topped with razor wire. Inside, the classrooms were cheerful and looked like an average elementary school with students’ birthdays and facts about historical figures pinned on the walls.

We waited outside while the military got themselves organized with the party representatives inside the compound. The military was responsible for bringing the ballots to the parties. Some Libre candidates had expressed worry that this could result in fraud if the military decided to sabotage Libre’s chances by not bringing their ballots. As it turned out, ballots and election materials for all three parties arrived about one hour late.

We stood outside the school in the early morning sunshine, looking around the narrow street. A handful of people had arrived early and were waiting. They read our t-shirts and stared at us. I was mildly uncomfortable at first. Was there a level of arrogance in our presence as first-world observers?

We stood outside the school in the early morning sunshine, looking around the narrow street. A handful of people had arrived early and were waiting. They read our t-shirts and stared at us. I was mildly uncomfortable at first. Was there a level of arrogance in our presence as first-world observers?

Eventually, a woman approached us to introduce herself and ask us about what we were doing. She enthusiastically thanked us for taking an interest in her country’s elections, adding that she was afraid of fraud and wanted to the world to be aware of Honduras and the political situation. After that, people continued to introduce themselves to us, ask us questions and thank us for our presence. My apprehension abated. When the military finally opened the gates for voting to start, a group of people ushered us to the front of the line and demanded the soldiers let us in first so we could observe the process and fulfill our mandate.

Each party had their own tables to carry out the voting process. There were four ballots and corresponding boxes per party — people were voting for a presidential candidate, multiple congressional candidates, a mayoral candidate and internal leadership of the parties. Libre only had one presidential candidate — Xiomara Castro Zelaya — the wife of ousted president Manuel Zelaya. This was strategic on the part of the FNPR. With four internal currents in Libre representing various positions on the Left, they had chosen to only put forward one presidential candidate to unite the party. The kind of infighting that Libre avoided in the primaries was evident on election day as the National Party presidential candidate race sparked a fist-fight outside one of the polling stations we attended.

Voters filtered into the station, often standing around in small groups afterward to socialize with neighbours or chat with the observers. One of the Libre Party workers complained that the Liberal Party was trying to steal their voters by telling them they didn’t need to vote for a presidential candidate because Xiomara had already been chosen, so they may as well vote in the Liberal primary. This might have been a ploy to boost the poor showing at the Liberal Party polls. Most of our observers reported seeing the most voters at the National polls.

Though we were prepared to see violence, none of the observers reported any overt incidents of oppression. Some of the observers said identity cards that were needed to cast votes were not delivered in some areas. At another voting station, stairs made accessibility difficult for disabled voters. The ink that was applied to people’s fingers as proof of voting was very light in some locations, or simply rubbed off immediately after voting. The military met our groups with varying degrees of friendliness or aggression — one group was followed around by a soldier, but at one of the stations I visited, a uniformed, bashful teen with an automatic weapon tried out a few English words with me. Many of our group were interviewed by the press.

The most startling report from our group came from long-time activist Charlie Hinton, who spoke with a man identifying himself as a former member of Battalion 3-16. This soldier explained that death squads and torture were necessary tools in the political-military apparatus. According to Hinton, the man was proud of his work. Hinton’s full report of his interaction is printed in the Counterpunch newsletter.

At the counting station in the upscale Hotel Maya, the day after the primaries, one of the mayoral candidates approached us with tally forms from the vote count. He alleged fraud to skew the results in the favour of another candidate and showed us where the numbers of counted votes had been changed in pen. Some of the members of another party we spoke to, as well as a sociologist, suggested the final vote count for the Liberal Party had been inflated to make them look like a more viable challenger for the incumbent National Party than the upstart Libre Party.

The next day we visited the final vote-counting locations … click here for the photo essay.