Stretching has been a part of my workout routine for years. It seems like a natural, common-sense activity. I had always assumed it was playing an important role in my health and fitness. Recently, however, I was irritated to discover that many of the reasons I spend time stretching have been invalidated by science.

For example, I’ve always been told to stretch before exercising in order to reduce risk of injury. But a number of studies—including one that involved over 2 700 Vancouver joggers—have found no evidence that this works. In fact, some studies have found that stretching for more than 60 seconds can negatively impact your performance by temporarily reducing muscle strength. Stretching doesn’t even appear to reduce muscle soreness, whether it’s done before or after a workout.

But old habits die hard. As long-time stretching enthusiasts like me will be quick to point out, there is another reason to stretch: increased flexibility. Flexibility increases your range of motion by allowing you to extend your muscles farther than you would normally. This helps you to do things that less flexible people can’t. Besides, I’ve always assumed that flexibility is the result of having healthier, more resilient, and more supple muscles.

Annoyingly, scientists disagree.

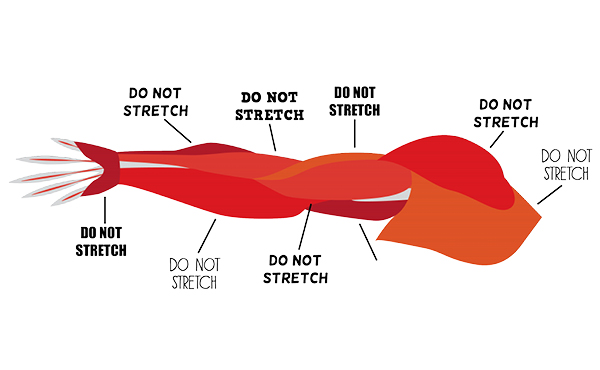

It is true that chronic stretching can increase flexibility—at least in some cases. But evidence is mounting that increased flexibility may not reflect a physical change in your muscles. Instead, the science suggests that flexible people are simply able to tolerate longer stretches than inflexible people. In other words, when you stretch you are modifying your sensory apparatus, not changing your muscles.

That’s not to equate flexibility with pain tolerance. The limit of your flexibility is very real and you can’t just push past it with machismo. Nonetheless, it’s a limit that appears to be neurological, as opposed to mechanical in nature.

If that’s true many of us may have to re-evaluate the benefits of flexibility. Indeed, for all I can tell, a greater range of motion is the only benefit flexibility confers. And while this may be desirable in certain situations, it’s not clear to me that having a greater than normal range of motion is an overly important aspect of fitness.

So does all this mean that stretching is a complete waste of time? Maybe. But, somehow I doubt that I will ever abandon it altogether. Besides, I have one reason to stretch that has yet to be exploded by science: I enjoy it. It just feels good. And, until the day it’s discovered that stretching is downright unhealthy, that’s the only reason I really need.

Eventually, I might even forgive the nosy scientists who have robbed me of my comforting illusions about stretching. After all, it’s probably for the best. Those of us who enjoy stretching can keep on stretching, and those of us who don’t can opt out in good conscience.