With syphilis cases rising in B.C., researchers hope to further understand and eliminate the STI

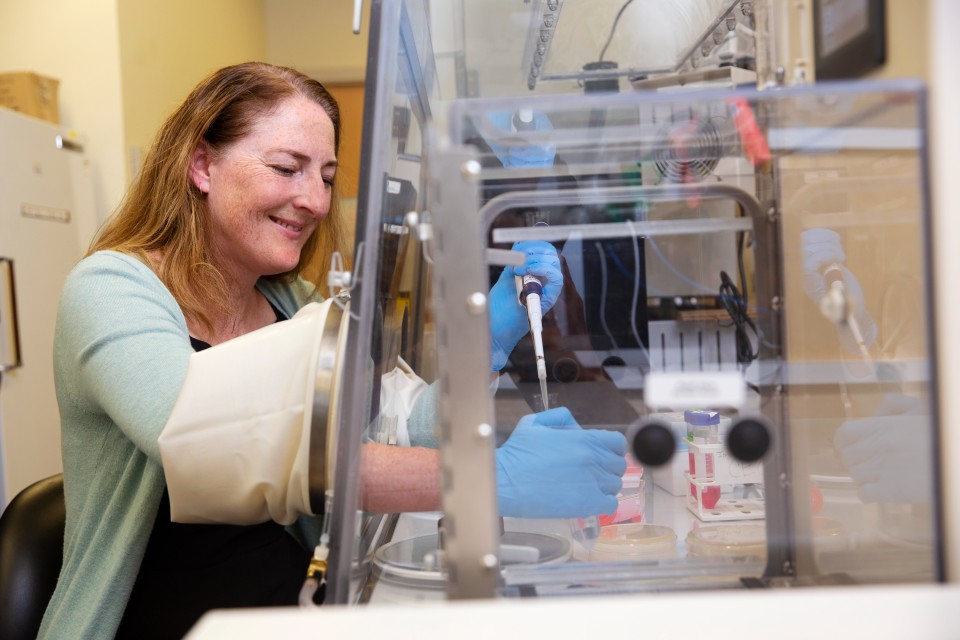

A University of Victoria microbiologist, Caroline Cameron, recently received an impressive 2 million US dollar grant from Open Philanthropy, a U.S.-based research and grant-making organization. This is the largest grant Open Philanthropy has ever given to a single Canadian university.

Cameron was granted these funds in order to help her research for developing a diagnostic test and establishing a vaccine for syphilis. After decades of declining cases, syphilis is on the rise again, with yearly global case numbers ranging in the millions.

The Cameron Laboratory is the only lab in Canada that is studying Treponema pallidum, the bacterium that causes syphilis. As Cameron explained in a press release with UVic, “So little is known about the bacterium that causes syphilis. If we want to eradicate the disease there is a lot of work to be done and to do it scientists need support from philanthropists, funding agencies and policy-makers.”

Syphilis is an infection that can be transfered via anal, vaginal, and oral sexual contact with a person who has a syphilis infection. It can also be transferred through skin-to-skin contact via syphilis lesions — small, often painless sores that tend to crop up on the genitals, anus, tongue, or lips, typically at the site of the disease’s first entry into the body.

Additionally, pregnant women can transmit syphilis to their unborn child. Passing syphilis on to unborn babies is often extremely dangerous for the baby, as untreated syphilis during pregnancy can lead to early birth, deafness, low birth weight, deformities, neurological issues, and even death.

When syphilis is caught early, it can be treated and cured with antibiotics. If the infection is left untreated, more serious damage to the brain, heart, and other organs can occur. It can be diagnosed with a blood test.

Many people believe syphilis is a disease from a bygone era, but the rates of syphilis in Canada have peaked for the first time in over thirty years. The rates of syphilis infections in Alberta are at their highest since 1948, and syphilis infections among women in B.C. between the ages of 15 and 49 have risen by almost 40 per cent between 2017 and 2018.

Why is syphilis on the rise again? There are numerous reasons this infection has been trending upwards. Some of these reasons could include lowered public health funding, which results in less public STI clinics and less sexual health resources, a lack of prenatal care for at-risk women who are unhoused or suffering from drug addiction, an increase in the use of dating apps which render the spread of STIs more difficult to monitor, and a decrease in the use of condoms.

Syphilis infections often have no symptoms, which is why in 2019, Provincial Health Officer Dr. Bonnie Henry and the BC Centre for Disease Control urged British Columbians to consult with their doctor about testing for STIs, especially for people who are pregnant or have a new sexual partner.

In a press release about the rising syphilis infections, Dr. Bonnie Henry explained that, “After seeing syphilis infections decrease for several years, rates of syphilis began to climb again earlier this decade … we need the public to be aware of the risk and to be proactive about testing and treatment.”

There are underlying determinants, such as structural oppressions that marginalized social groups endure, that make some people more at risk of contracting syphilis. For example, young Indigenous men who experience the ongoing effects of colonialism and these structural oppressions within the healthcare system have an increased risk of contracting syphilis.

Additionally, having a low income, living unhoused, or being incarcerated are associated with an increased risk for syphilis. Gay and bisexual men also tend to be at higher risk for syphilis due a range of social, economic, and structural factors, including homophobia in the healthcare system and access to health services.

Currently, syphilis testing has drawbacks as a test can struggle to differentiate between current and prior infections. Importantly, there is no vaccine to prevent a syphilis infection. Cameron’s team is working on understanding the bacterium that causes infection, which will help develop more compelling diagnostic tests and future vaccines.

The Cameron Laboratory’s goal is to find a way to finally snuff out an affliction that has impacted and killed humans for over 500 years. While this research is important regionally as syphilis cases continue to rise in B.C., Cameron’s research has global implications — syphilis has and still is the most devastating in low and middle-income countries.

As Open Philanthropy Scientific Research Program Officer Heather Youngs said in the UVic news release, “Developing effective diagnostic tests and a vaccine for syphilis could prevent hundreds of thousands of deaths.”