The trail on the journey between the MacLaurin building end of the quad and the Engineering building is as eccentric as routes between classes go. It seems like a trek through the wilderness, except it’s less than 100 metres long. Like most places on the UVic campus, there is history there. The woods that the path cuts through might not exist if not for a student protest that camped out in the trees there 10 years ago.

This patch of Douglas fir forest is called Cunningham Woods. In late December 2002, part of the woods was cut down to make way for the new Medical Sciences building. This had been a controversial issue for months and the sudden clear-cut spurred the passion of a rotating group of a hundred students who set up platforms in a Cunningham Woods arbutus tree. They refused to leave until the university made a guarantee that the remaining forested areas on campus would not be cleared for further development.

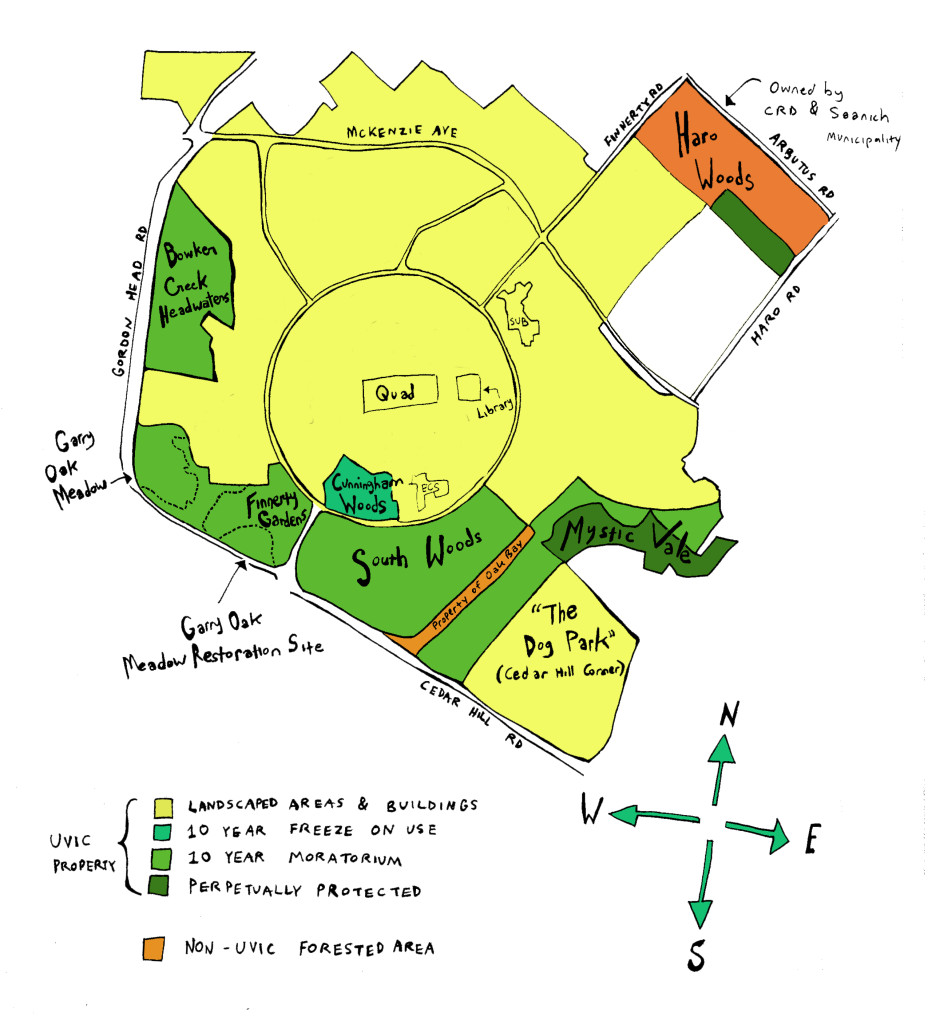

UVic’s current campus plan was being drafted at the time. Under public pressure, the planning committee met the demands of the activists by including a 10-year ban on development in five areas: Bowker Creek Headwaters, the Garry Oak Meadow, South Woods, and Cunningham Woods. These were added to the perpetually protected-status areas of central Mystic Vale and Haro Woods.

Not only does the plan include a development ban, it also supports the restoration of these ecosystems. It suggests that new buildings should be constructed on lawns or, preferably, parking lots. The Medical Sciences building was still constructed on part of what had been Cunningham Woods, but in tune with the new campus plan, the Engineering/Computer Science building was put on a parking lot. The five wild areas are still around, and ecosystem restoration is an ongoing process in all of them.

This brings us to the present. The 2003 campus plan is about to expire, and so will the development moratoriums. A new generation of student environmentalists is beginning to advocate that, as part of the updated campus plan, the same areas that were given 10-year moratoriums should be permanently protected.

Why are UVic’s natural areas important? There are a lot of arguments.

The Garry Oak Meadow, in the words of the campus plan, is “a rare ecosystem that is critically threatened throughout its native habitat.” Here, the Garry Oak Meadow Restoration Project has been underway for several years as a partnership between UVic and community organizations. This is UVic’s part of a broader movement to restore Garry oak ecosystems throughout southern Vancouver Island.

The neighbouring Bowker Creek Headwaters is a wetland Douglas fir forest. One of two tributaries that lead into Bowker Creek begins here. From UVic and the other tributary at Cedar Hill Golf Course, the creek flows south and meets the sea at Oak Bay. It is the key waterway in the Bowker Creek watershed, but many don’t know it exists as a continuous stream, because it is mostly underground, buried in culverts underneath houses, roads, malls, and parking lots. The Bowker Creek Headwaters at UVic are especially significant considering that the municipalities of Saanich, Victoria, and Oak Bay have adopted a 100-year plan to uncover the stream wherever possible and restore the health of the watershed. Preserving areas like the headwaters that are already in a natural state is important to this plan. This forest also has a wider variety of bird species than anywhere on campus.

The outskirts of Mystic Vale are under a 10-year moratorium, while the centre is perpetually protected. The ravine is known for its beauty and is significant to the WSÁNEĆ people. Because of its biodiversity, it is the site of many research and restoration projects. South Woods arguably is especially valuable to the Biology and Environmental Studies departments and links the Garry Oak Meadow to Mystic Vale. Together, these areas form a green ring around half the campus. Connected corridors like this are important for wildlife that have an easier time surviving in wild areas that aren’t broken up by expanses of pavement.

According to Lexi Fisher, a fourth-year Environmental Studies, Geography, and Restoration of Natural Systems student, the biggest reason to preserve natural areas may be stormwater filtration. A study on campus natural systems in 2007 found that 23.5 per cent of the campus is covered by cement and other impervious surfaces.

“All that runoff water needs somewhere to go,” Fisher says. “In urbanized areas with a large amount of impervious surface, the water builds up and rushes over the landscape, picking up pollutants and other sediments.” This leads to erosion of stream banks and causes pollution to run into streams and make them uninhabitable to wildlife. In natural areas, this doesn’t happen, because water is filtered through the soil.

Many students choose to come to UVic because of its beautiful campus. To them, the university’s landscape and commitment to sustainability might be its most likeable features. The forest provides running trails. It is used for teaching and research in the field (and the field is directly outside the lecture hall). It also preserves plants and animals that are the subjects of Coast Salish traditional knowledge.

That said, many departments are in need of more space. Pressure for development will continue as UVic expands its capacity, and land may become an issue. The updating of the campus plan is scheduled to begin in late 2014. Meanwhile, Fisher thinks the goal is to “Let UVic know that the student body cares about the future of our green spaces.”

Currently the UVic Students’ Society is co-ordinating UVision, an initiative that organizer Matt Hammer describes as “an ongoing process to get students’ ideas on how to make a more sustainable campus and push for them to be included in UVic’s revised campus plan.”

“It started with a vibrant open house last January,” says Hammer, “and is going to be continuing this fall with more working groups and outreach. The campaign plan after that is still being worked out, but we’ll gather more and more momentum as we approach the actual campus plan review.” At UVision and elsewhere, UVic’s wild places are likely to be a topic of debate in the next year.

Emily Thiessen (Graphic)