In 2007 the term ‘financial crisis’ found its way into the headlines when the first U.S. banks started to struggle. Since then it seems as if it has never left the front page. U.S. debts, Greece’s financial ruin, the EU’s struggle in general, the downgrading of financial creditworthiness for companies and entire countries — these topics are still in the news on a daily basis, but how long will they stay there?

“Five years into the crisis: What lies ahead?” asked UVic’s Faculty of Social Sciences in a panel on Nov. 21. Five experts answered: Dr. Amy Verdun, professor and chair of political science at UVic; Dr. Paul Schure, associate professor of economics at UVic; Dr. Basma Majerb, assistant professor at the Gustavon School of Business; Dr. Adriaan Schout, deputy director of research at the Netherlands Institute for International Relations; and Tony Cage, director of PSP Investments and Sky Investment Counsel.

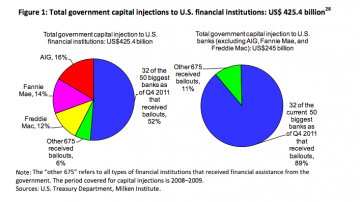

The panel addressed several topics regarding the financial crisis and shared interesting facts about what had happened. Majerb, for example, discussed the concept of banks “too big to fail” and its consequences: 89 per cent of the U.S.’s Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), which is for the purchase of distressed assets, funded 32 big banks in the U.S. The rest, 11 per cent, went to 675 smaller institutions.

However, the focus of the panel was mostly on the future and what lies ahead. “Oh, it’s going to be a turbulent time,” said Verdun to the Martlet after the panel. “We’re not over the hill. We had to decide what was the title of this panel; we chose ‘Five years into the crisis.’ We might actually be looking at a decade. Some people say above a decade, but we don’t want to be quite so negative. So, we’re just saying that we’ve had our difficult five years and we’re not completely over the hump.”

During the panel, high youth unemployment rates as a result of the financial crisis were mentioned, especially those in some European countries. In October 2012 Eurostat, the statistical office of the EU, presented harmonised unemployment rates for EU countries. Currently, the 27 members of the EU (EU27) have an average unemployment rate of 10.7 per cent and this number is on a rising trend. Since last fall, it has increased by nearly one per cent. The unemployment rate for young people is especially dramatic: currently the youth unemployment rate in the EU27 is 23.4 per cent. In a few European countries it is higher than 50 per cent, such as in Greece (57 per cent in August 2012) and in Spain (55.9 per cent).

In comparison, the U.S.—also hit quite hard by the financial crisis—currently has a general unemployment rate of 7.9 per cent and a youth unemployment rate of 16 per cent according to Eurostat. Canada’s unemployment rate was not given by Eurostat. Unemployment rates from different sources are not easy to compare; it depends on which groups of not employed people are included. Using a different source would only add confusion.

According to Verdun the recent struggle of the EU has to do with a government structure that doesn’t allow it to react quickly. Even though the EU is working on an overarching federal structure, it is still important to keep in mind that this union is the first of its kind — democratic body of independent states.

“I’m optimistic that the EU will solve the crisis as it is. It might be a very healthy crisis, actually, because the EU consists of really semi-failed states or completely failed states. And the EU can only flourish if the countries individually are strong enough,” said Schout to the Martlet after the panel.

“Now, the EU needs a strong internal market. So, it is actually very healthy that we now see these countries like Italy, and also France mind you, really need to reform, because otherwise the EU will not have enough of an industrial base to grow and be prosperous. So, maybe we’re laying the basis of a much more competitive EU.”

At the G20 summit in Los Cabos, Mexico, 40 countries decided to contribute money to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in support of Europe. They collected US$450 billion and Canada wasn’t one of the contributors. Whether the bailout plan will work or not, Canada’s refusal to join in might tarnish its reputation.

“Canada is naive to think that a major European crisis is something that Canada would just ignore,” says Verdun.She adds that governments in general should pay more attention to the people at the weaker end of society.