UVic’s inclusive Walk of Silence

Content warning: This article contains description of the 1989 École Polytechnique massacre

On Dec. 6, 1989, 25-year-old Marc Lépine entered a classroom at École Polytechnique in Montreal with a hunting rifle. He ordered the male engineering students from the room, gathered the women together, and opened fire. After leaving that classroom, he roamed through the halls, the cafeteria, and another classroom, separating female students from their male colleagues and shooting to kill. By the time Lépine turned his gun on himself 20 minutes later, 14 women were dead and another 10 were injured. Four men were unintentionally injured.

The Montreal Massacre was one of the worst mass shootings in Canadian history, and also one of our country’s most infamous examples of gender-based violence.

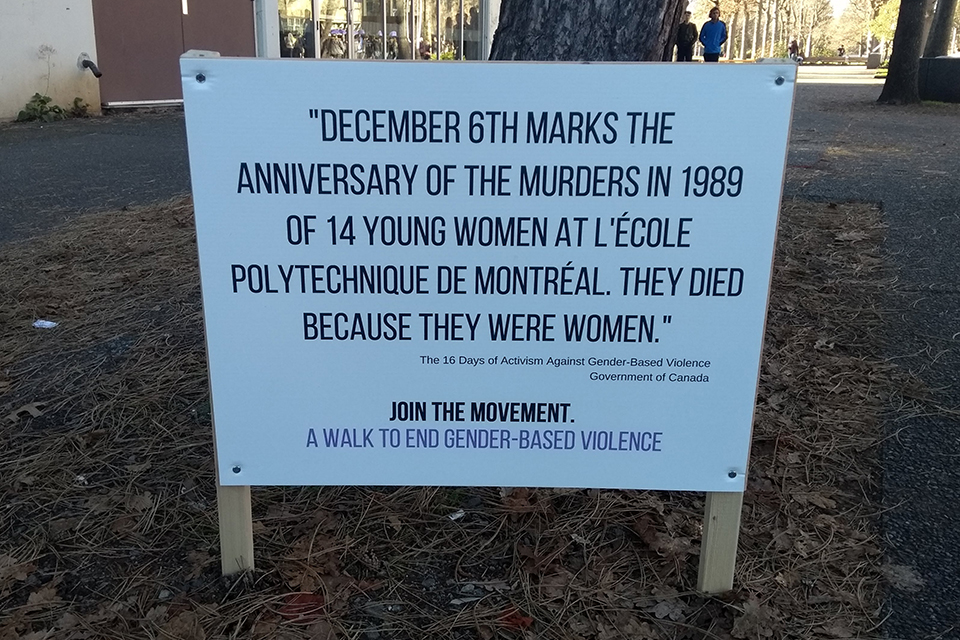

On Dec. 4, 2019, 30 years after the slaughter, people of all genders gathered in front of the University of Victoria’s Student Union Building (SUB) to acknowledge gender-based violence in all its forms. Although it coincides with the National Day of Remembrance and Action on Violence Against Women, which occurs on Dec. 6, in memory of the Montreal Massacre, the UVic event is broader in scope.

“We have intentionally broadened the focus of this day to include all gender-based violence, not only that against women and girls, in recognition that trans and gender non-conforming/non-binary people encounter disproportionate rates of sexualized violence and we need to work in solidarity to address the different forms of violence together,” said Leah Shumka, a Sexualized Violence Education and Prevention Coordinator in UVic’s Equity and Human Rights Office (EQHR).

Every year, EQHR and student advocacy groups collaborate to host the event. Classes were cancelled between 11:30 and 12:30 to allow students to participate.

The event, emceed by Serena Bhandar of the Anti-Violence Project (AVP), began with a territory acknowledgement by Gary Sam of the Songhees Nation and included several speakers. Vice-President Academic and Provost Valerie Kuehne spoke about programs at UVic that combat gender-based violence and support survivors. Acting Dean of Engineering Peter Wild discussed his faculty’s commitment to addressing gender-based violence. Billy Yu, who works with AVP’s Men’s Circle, spoke about the need to unlearn toxic masculinity. The 2019 City of Victoria Youth Poet Laureate, Aziza Moqia Sealey-Qaylow shared one of her poems. From the gathering place outside the SUB, the crowd set off on a Walk of Silence around the quad. Following the walk, participants gathered in the SUB’s Upper Lounge for hot drinks and art activities.

“Our silent Walk to End Gender-Based Violence is an important moment to commemorate past events, and reflect on the steps each of us can take to actively work to end gender based violence,” Shumka said. “When we walk, we show our solidarity to end violence in all its forms on people based on their sex and gender.”

The tragedy at École Polytechnique is remembered throughout Canada, but especially in engineering faculties.

“I feel that if we don’t [commemorate the Montreal Massacre], there is the risk that people will forget about it,” said Charlene Hewitt, an administrative officer in the engineering undergraduate office who has been participating in this event since 2010. “I like that the walk now covers all gender-based violence, and so it’s more inclusive.”

Hewitt feels that the inclusivity offers greater support to more people. “A lot of it is about support and coping,” she said.

In 1989, the media portrayed Lépine as a madman and the female engineering students simply as bodies in his way, rather than specific targets. Police refused to release his suicide note, which Lépine had pinned to his body, saying that it could inspire copycats. But, the Montreal Massacre was not the random act that 1989 Quebec wanted to believe it was.

Lépine’s note revealed that he had “decided to send the feminists, who have always ruined my life, to their Maker.” The note also included a list of names and phone numbers of 19 women deemed by Lépine to be feminists — women he wanted to kill. According to the note, “the lack of time (because I started too late) … allowed these radical feminists to survive.”

Francine Pelletier, in 1989 a feminist activist and columnist for the Montreal newspaper La Presse, was one of the women on Lépine’s hit list. 30 years later, in an article published by CBC, she commented on how the massacre of students at École Polytechnique has been treated as an episode of the violence that women have always endured — and how the reality is more complicated.

In the late 1980s, women’s rights were increasingly pushed to the fore, and Quebec was no exception. In 1988, a landmark Supreme Court ruling determined that denying women access to abortions is a violation of women’s Charter rights. It was also a time of backlash from men who blamed women, especially feminists, for their perceived misfortunes. In this environment, Lépine became what Pelletier calls a trailblazer for “incels” who blame women for their “involuntary celibacy.”

“Lépine instinctively knew that the more liberated women became, the less likely they would choose a man like him: angry, reactionary and forlorn,” said Pelletier. “Feminists were not so much taking up his space [at École Polytechnique] as denying him the emotional and sexual companionship he craved.”

For Pelletier, the Montreal Massacre wasn’t simply an act of violence against women, but part of a war on feminism that she believes is still ongoing, and that centres around men’s access to women’s bodies.

“How,” Pelletier asked, “could we not have seen that there would be a price to pay for feminism?”