The apparent absence of class distinction is a peculiar feature of university life. Socioeconomic class is something we dislike discussing yet remain fascinated by. Daniel Craig’s rebooted James Bond is compelling in part because he assumes a rugged working-class air while absolutely dominating in a world characterized by opulence. Prior to his 2008 election, Barack Obama relied on a narrative that highlighted his racial identity as much as his struggles to find success in the American middle-class. In our politics and our entertainment it is clear that we love an underdog and disdain entitlement.

Yet, somehow, discussions related to socioeconomic class fall outside the purview of students. Part of this can attributed to students’ justifiable wish to avoid long-winded monologues inflected by Marxian or Occupy Wall Street-type rhetoric. ‘Class dialogue’ in the university setting tends to be awkward, one-dimensional and didactic, characterized by over-eagerness that either shames or romanticizes a particular group of people. The subtleties are lost in favour of heavy-handed value judgments. Additionally, talking about ‘class-struggle’—real or not—is sort of going to harsh your buzz in just about any situation. However, there are huge swathes of the world—probably the majority—where class is simply accepted as a daily truth. Everything from dialect to your taste in tracksuit bottoms to your neighbourhood to your parents determines who you are and where you’re going in life.

In Canada, class distinction is undeniable but isn’t inescapable either. However, class continues to be a very real dimension of personal identity, alongside other factors like ethnic background, gender identity, or sexual orientation. It’s difficult to acknowledge class distinction in university because the distinction between individuals isn’t obvious: students from any background think that Breaking Bad kicks ass, and have an abiding love-hate relationship with tequila night. Tastes and preferences in the 21st century overlap, irrespective of one’s background.

Moreover, Canada has a strangely egalitarian attitude in which wealth is ostensibly only a measure of one’s finances, not an indicator of snobbishness. Generational wealth is simply not part of our social milieu. Once upon a time, the general perception was that a wealthy adult would have cultivated a taste for wine and opera. Or similar, a working-class person would be more of a beer-drinker and soap-opera-watcher. Today, these kinds of assumptions are totally unreliable. People now have access to virtually all of the world’s art and academia, past and present. In the past they would have been limited to the culture associated with their own particular region and class.

Despite overlapping tastes, individuals from low-income and relatively high-income backgrounds do have different cultural references and sensibilities, and don’t live in substantially the same way. Class distinction in university is more or less an issue of slanted outcomes and consequences. Most of us have at least several wealthy friends who flunked out in first year and are now working for their Dad’s accounting firm, earning more than an average entry-level lawyer on Bay Street (and without any of the presumable debt).

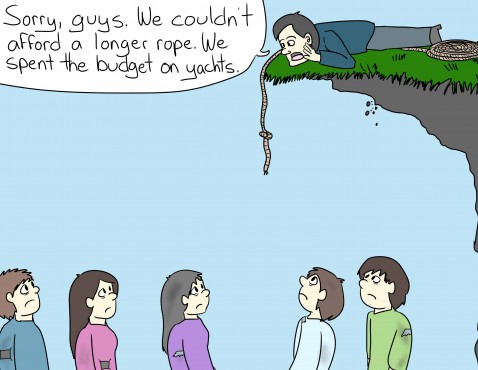

Clearly they’re the exception, not the rule; however that safety net (or the absence of one) truly does set individuals apart from one another. The choices we make, our willingness to question, take risks, or conform, and our knowledge of what’s available to us in the world, are all partly contingent on how much money we have. The wealthy aren’t bad people or somehow morally inferior because they have easier access to opportunity; but their charm and lifestyle are things that they can afford to have. Conversely, being on the opposite end of the spectrum doesn’t indicate a natural propensity for hard work and thriftiness.

Additionally, a marked divide in perspectives tends to exist between low-income and high-income individuals. Generally, the affluent have a greater tolerance for difference and a predilection for effecting change (necessary or not). To paraphrase frat-lit writer Tucker Max: Try testing your moral resolve in a crucible of suffocating debt. Want to accept that prestigious unpaid internship or go traveling indefinitely? How about volunteer for beach cleanup or park conservation for a year? Too bad—we’re still in a down economy and the interest payments on your student debt are accumulating. Moreover, pipeline companies in Alberta are offering $45 000–50 000 a year starting salaries for general degrees. Which decision would you make?

The middle class tried to bridge the most extreme gaps between the lower and higher end of the socioeconomic spectrum—at least in principle. Aspiring to be or remain middle-class was reasonable; now it’s becoming impossible. Either you make the sacrifice to insinuate yourself into the shrinking elite, or resign yourself to something lower than you feel you may deserve.

As the financial security of ‘middle-class-ness’ erodes, middle-class identity seems increasingly and unsettlingly obsessed with political correctness and adhering to the ‘right’ values. In recent history, being middle-class meant a good education and the promise of a better future for one’s children—not moral affectations. It meant retaining some independence, while operating in a society that works on someone else’s terms, having a slightly stronger say. Increasingly, it equates to being stuck between worlds, enjoying neither the solidarity of the so-called working classes, nor the financial independence, autonomy and authority of the upper classes.

It’s unreasonable and unfair to demand that the wealthy give up their station in life or feel guilty simply because they have what everyone else wants. Nonetheless, the bitterness and disillusionment expressed by those struggling is real, and shouldn’t be ignored in a university or in Canada.