What would have happened 20 years ago if British Columbia’s universities announced a plan to double tuition fees, slash grant programs, increase class sizes and cut back on lab and tutorial sessions all at once? Can you imagine the outrage if students were suddenly told to pay twice as much money for fewer services?

These changes did happen; they were just introduced piecemeal to a student population that renews itself every few years. Small annual tuition increases, unpublicized clawbacks of grant programs, and a cancelled seminar here or there produced new normals that were inherited each year by a fresh cohort of students. Most people have lost track of their overall impact, but over the past two decades a radical transformation to the nature of university education has taken place right beneath our noses.

Undergraduate tuition has gone from $3 000 per year to $6 000. That fact alone is cause for concern, but the price tag only tells part of the story. There have also been a whole slew of more insidious and perhaps more threatening changes that are effecting the very nature of teaching and learning in our post-secondary schools.

There are some students at UVic who have done their undergraduate, masters, and PhD programs in British Columbia and have experienced the changes to education first hand, but finding one who will talk about it on record is almost impossible. There is very little job security for TAs and sessional instructors and no real guarantee against academic harm for people who speak out against their departments.

“My department chair literally holds my career in his hands right now,” said one PhD student who asked to remain anonymous. “There is nothing in our collective bargaining agreement that protects me from being targeted if I speak out so there is no way I want to go on record.”

This person is a UVic lecturer who started his academic career in 2004 as a TA at another Canadian university. Back then, he led tutorials for first year courses that usually consisted of 10–12 students sitting in a circle sharing ideas about a book they had just read.

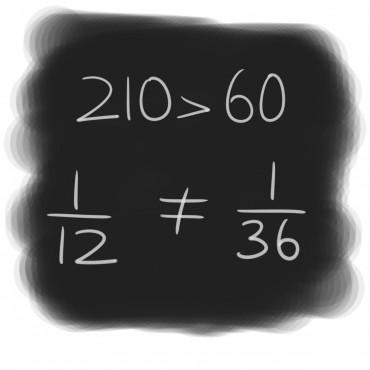

“We [teaching assistants] were hired for 210 hours per semester. That was enough to prepare for seminars, hold office hours, and give adequate feedback. Back then I was able to be good teacher.”

In 2014 he led similar first year seminars at UVic, except instead of 210 hours of work to teach a dozen students he was paid for 60 hours to teach three dozen—a third of the time to teach triple the students.

“I can honestly say that in 2014 I had to work twice as hard for less money.” He went on to state, “I know that many TAs are working for free now, and they won’t speak up because they are afraid of departmental politics. No one wants a bad reputation with the people they have to ask funding letters from, and there’s no job security.”

Worse still, he explained that the reduction in hours and increase in class sizes has made a dramatic difference in the quality of instruction. Teaching assistants at UVic are now being told not to provide feedback on student papers.

“We are told to make no editorial comments, no grammatical corrections, give no attention to actually teaching writing skills; students just get a mark and a one-line comment that says ‘See the Writing Centre’ if they didn’t do well.”

Levels of student engagement have changed too. Skyrocketing tuition fees and the obvious shortage of grants and loans are forcing many students to work full time while taking four or five classes per semester. The result is that they have less time for actual learning and university becomes an inconvenient pit stop in their careers rather than a fulfilling rite of passage.

“It’s clear to me that these problems aren’t unique to my department at one university,” said the TA I spoke with. “The same pattern is occurring at schools across the province. The only thing that seems to be growing is the number of senior administrators who make a quarter-million per year.”

The problem doesn’t just involve teaching assistants; universities are contracting out more and more teaching assignments to sessional instructors. Sessionals are paid a flat rate per course so their hourly wage depends on how much work they do.

“The first time I was a sessional I taught a 180-person lecture course, I love teaching and I cared about my students so I did my best to prepare for classes and create a good learning environment. I made about $9 hour. There is literally a disincentive to being a good teacher.”

Teaching assistants and sessionals at UVic are at the bargaining table negotiating new contracts right now. In the current political environment where every other public sector union has already caved to the BC Liberals’ austerity agenda, this union has an uphill battle to fight, but it’s a battle that has been won before in other provinces. The recent student revolt in Quebec and the decade of successful labour campaigns at York University in Toronto are evidence of the power that students and TA unions have to transform their societies.

Gordon O’Connor is the vice president of CUPE 4163. To find out more about their campaign, visit facebook/cupe4163.