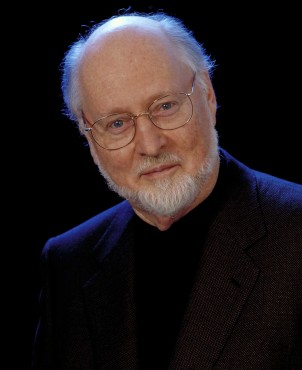

Renowned composer John Williams returns for the seventh instalment of the Star Wars franchise, The Force Awakens. Photo provided via Wookieepedia

When the first teaser trailer for The Force Awakens premiered last November, it didn’t take much to get me excited. The promise of new stories and adventures in the galaxy I’ve grown to love is reason enough, and the first peek at alien worlds and unfamiliar characters mixed with classic imagery reimagined for a new generation was gravy.

But what stirred my emotions when watching that teaser one year ago wasn’t what I saw. It was what I heard. John Williams, mastermind behind the score of Star Wars and so many other classic films, was bringing his signature style to the galaxy far, far away once again, and as the Millennium Falcon roared on screen with the fanfare blaring, I was floored.

For many like myself, John Williams is Star Wars. His work is intrinsically linked with the series at large, thanks in part to memorable themes that have taken over the cultural zeitgeist, and his ability to tell a story through the music itself.

It’d be easy for me to wax poetic about Williams on my own, but to lend some expertise to this article, I spoke with Anita Bonkowski, an instructor at the UVic School of Music. According to Bonkowski, Williams’s compositions are based in the classic film score tradition of the 1930s, which is characterized by an “extensive use of music . . . using the full range of the orchestra,” and the establishment of themes and moods through leitmotifs (a musical theme that represents a character or idea) and “thematic transformation.” Bonkowski says this style of composition, influenced by Richard Wagner and opera, fell out of vogue in the ‘50s, but Williams brought it back into prominence for A New Hope in 1977.

[pullquote]Willams’s work is intrinsically linked with the series at large, thanks in part to memorable themes that have taken over the cultural zeitgeist, and his ability to tell a story through the music itself. [/pullquote]

Williams borrowed from other 20th-century influences as well. For example, elements of Gustav Holst’s seven-part suite, The Planets, made their way into Star Wars; in particular, Bonkowski notes that the final notes of “Mars, the Bringer of War” forms the basis of the accompaniment to the destruction of the Death Star. Elements of Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring were also used in “The Dune Sea of Tatooine.” (Unrelated to Star Wars, but I had a friend in high school that insisted Williams’s theme for the first Superman film was ripped wholesale from Holst. Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, I would say.)

You may not know what a leitmotif is, but I guarantee you’d recognize one in the context of Star Wars. “The Imperial March (Vader’s Theme)” is one; “The Force Theme” (otherwise known as “Binary Sunset” in A New Hope) is another. I could go on — “Princess Leia’s Theme,” “Yoda’s Theme,” etc. These pieces are all instantly recognizable, and Williams draws on them throughout the six films (and, I assume, in The Force Awakens), tweaking and adjusting them to embellish and underscore what’s presented on screen.

A perfect example of Williams’s use of recalling previous themes to support the story is “Anakin’s Theme,” from The Phantom Menace. Williams relies heavily on woodwind and stringed instruments in the arrangement, and the melody captures the naivety, hope, and longing that are associated with the young protagonist. But listen closely, and you’ll notice that Williams ends the theme’s melody line with a familiar set of notes from the “Imperial March.” It’s subtle, and you’d miss it if you weren’t paying attention, but this aural callback to the original theme reminds us that as innocent as Anakin is in The Phantom Menace, his path will take a dark turn in the future.

But some of my favourite parts of Williams’s score aren’t the themes at all. In fact, they’re one-offs, written for a particular scene and never used again. One example is “The Asteroid Field” from The Empire Strikes Back, which, surprise, plays during the Millennium Falcon’s escape through an asteroid field (not very subtle, Williams). The piece is Williams condensed into four minutes: prominent brass, kinetic energy, and just so damn exciting.

Another personal fav is “The Battle of Hoth,” a 14-minute medley that encompasses the entire opening action sequence of Empire. Four minutes in, a combination of lumbering percussion and thudding piano signal the arrival of the Empire’s towering AT-AT walkers; they’re immediately followed by low brass, acting as a war horn for the coming battle. Perhaps it was endless hours playing Star Wars: Shadows of the Empire on my Nintendo 64 as a kid, but the opening notes of this musical accompaniment have been carved into my psyche, and never fail to stir that same feeling of excitement.

Jump ahead to Return of the Jedi, and we find Williams flexing his muscle a little more, using choral voices for the first time in the series. These are used primarily in scenes featuring the Emperor, and are downright eerie. While Vader’s theme is bold and powerful (like the character himself), the Emperor’s theme is seductive and low-key, capturing his role in the film perfectly.

Indeed, Return of the Jedi’s best scene (and my favourite of the saga, bar none), wherein Luke Skywalker unleashes his anger in an attack on Vader after the Sith lord threatens to turn Princess Leia to the dark side, is accompanied by straining strings and a harrowing chorus; it’s a bit of an outlier amongst the original trilogy’s compositions (Williams leaned hard on choirs for the prequels), but it captures the raw emotion and heartbreak that comes with watching Luke give into his darker impulses. I love it, and I watch the film in anticipation of that scene each and every time.

I’ve hardly touched on the prequel trilogy, which saw a more contemporary Williams branch out in his writing. One might say (and I think I will) that the prequel trilogy’s score, like the films themselves, have a different flavour to them. They simultaneously carve their own path while honouring what came before, with the odd theme from the original trilogy making an appearance.

I’ll be thrilled to see The Force Awakens, and part of that is knowing, regardless of how the saga unfolds on screen, that Williams’s accompaniment will offer a sense of new blended with a reverence for the old. The music of these films is like comfort food; memorable, reliable, and evocative of a time when good triumphed over evil, when heroes overcame the villains (okay, so not exactly like comfort food).

The opening crawl — and Star Wars fanfare — can’t start soon enough.

Editor’s note: It’s one thing to read about all of this; it’s another thing entirely to actually listen. If you have no idea what I’m talking about in this article, I’ve made a handy Spotify playlist just for you.