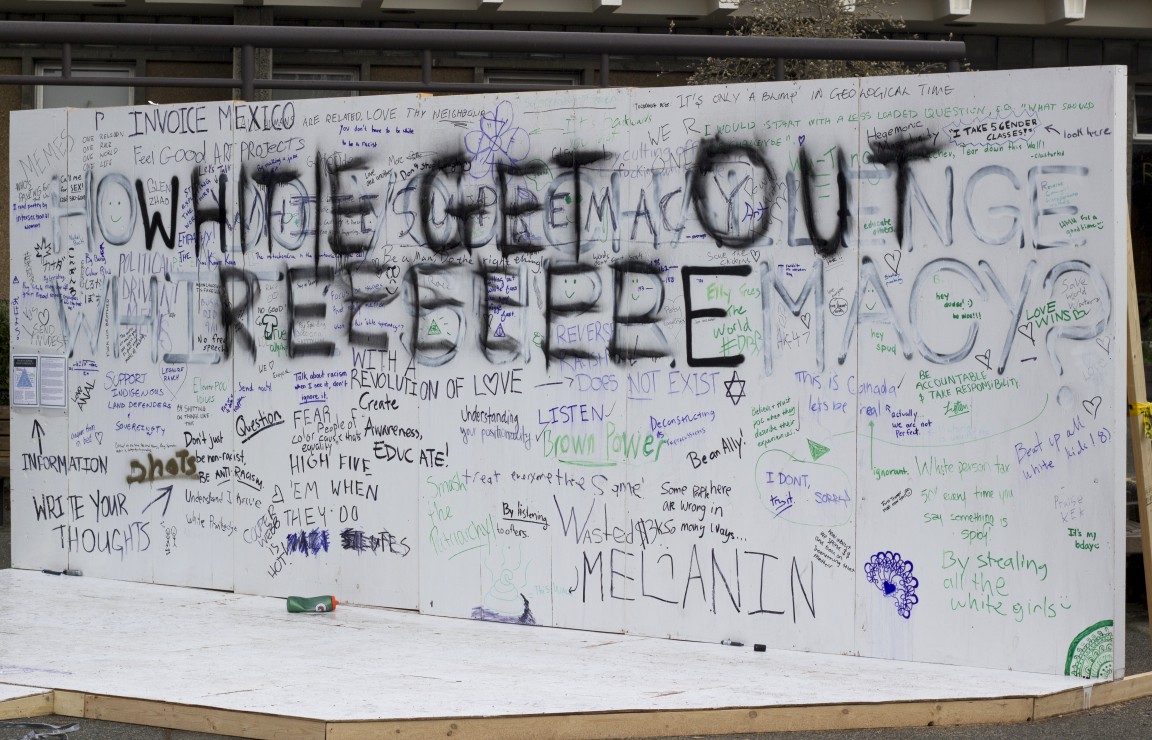

“Ironic” racism like this message scrawled on the Third Space art project proved that some UVic students can’t deal with the issue of racism on campus. Photo by Myles Sauer, Editor-in-Chief

If you were around campus last week, you likely saw or heard about the art project spearheaded by the Third Space: a wall, painted in stark white, with black lettering that posed the question, “How do you challenge white supremacy?” The project offered a blank slate for students to voice their thoughts in writing, and while the question could be read as pretty loaded, it succeeded in sparking discussion.

Students spoke face to face outside the SUB, on social media, and even on the wall itself. But it was the content of that discussion that drew the most attention, as anonymous trolls decided to use their voice in a way that was immature, destructive, and ultimately proving the point of the whole operation.

Conversations about race tend to make a lot of people uncomfortable, and for good reason: Canada doesn’t have the greatest track record when it comes to dealing with minorities, considering how often we gloss over the various atrocities in our history books. Public education hasn’t done the best job teaching young students about things like residential schools (though that’s now starting to change, albeit slowly), or the head tax, or the abysmal conditions that most people who live on reserves experience day in and day out. People aren’t exposed to the issues enough growing up, and as a result, it creates a misconception that racial discrimination just “doesn’t exist here.”

But let’s take a minute: how many of you heard about the escalating violence on campus that many Indigenous students experienced following the Native Students Union/Undergraduates of Political Science snafu of last year? How many of you knew about a UVic instructor who openly posted transphobic and Islamophobic content on a blog in 2015? Or that some instructors refuse to address transgender people by their proper names, or use their proper pronouns? Those all happened here on this campus, but unless you live those experiences of marginalization, it’s easy to fall into the trap of thinking those experiences don’t exist.

Contrary to what some of the wall’s detractors argued, white supremacy is not always draped in a white hood and obsessed with burning crosses. White supremacy is implicit. It’s systemic. It’s stitched into our social fabric and rendered invisible by the power structures that demand it be so. And it goes beyond individual instances of discrimination and manifests as something far more malignant.

The swastikas, the written assertions of “white power” and that “reverse racism is real,” and all the rest, are messages that support the fundamental structures of white supremacy as they operate latently in our everyday lives. Decrying the project by pointing out Canada’s diversity, or moaning about how you don’t like the way you’re being engaged in conversation, is privilege at its finest, and fails to recognize how this problem permeates our culture at every level.

Making people feel uneasy in a place where they don’t normally have to think about these things, where they’re not confronted by them day in and day out, is exactly the point of the Third Space’s project. For marginalized people on campus, this discomfort reflects their daily lived experiences. And what this project has shown above all is that when the shoe’s on the other foot, many people can’t take the heat.