An Australian child’s exposure to baseball is limited.

“Growing up I thought there were just two teams in the bigs; the Yankees and the Red Sox,” a Queensland-born minor leaguer once told me, “‘cause that’s all they showed on T.V.”

Since age 11, I’ve been collecting scraps of baseball facts — most from American movies—which I weave into my patchwork of knowledge. I’m still sewing up holes.

The first baseball films I saw were The Sandlot and A League of Their Own. Then came the understanding that Joe DiMaggio was not just Marilyn Monroe’s husband but a Yankee, and Yankees suck.

Then there was Field of Dreams, the 1989 film based on the novel Shoeless Joe, written by W.P. Kinsella, that centres on Ray, a farmer who (inspired by a voice in his head) builds a baseball field, risking bankruptcy and ridicule in the process. Ray searches for author Terence Mann (based on the reclusive writer, J.D. Salinger), who he has decided is the voice behind the prophecy.

It speaks to Australian ball fans who know heart-driven madness well; those whose peers kindly peel themselves away from watching four-day televised cricket tests to say baseball is boring.

Field of Dreams reminds me of the small and very dedicated baseball community down under, who battle the odds to make room for a decidedly American sport.

And it’s working.

Baseballisms are slowing seeping into the Aussie lexicon, evident on the day my mother, who usually takes books over balls, said to me, “My accountant’s a ball fan — he has a bat.” That’s the kind of magic Kinsella wrote about: the magnetic appeal of baseball. It’s how the saying goes: if you build it, he will come.

Well over a decade into my fandom, my university agreed to send me abroad to study, supplying me a list of possible institutions that I’d quickly dismiss for simple reasons: University of Waterloo (too cold), University of Montana (too remote), Simon Fraser University (too ugly).

The University of Victoria was solidified as my first choice after I discovered that W.P. Kinsella was an alum, a Martlet staffer, and the author of Shoeless Joe. I remembered Ray’s search for Mann and truth, and it reminded me of my need to know more about Kinsella.

When I signed my acceptance letter to UVic in August 2016, I reminded myself to look up Kinsella when I reached Victoria. He died the next month, on Sept. 16, at age 81.

Now, when I return to work on my baseball patchwork, Kinsella is at the forefront of my mind as I try to stitch together why he had such a profound impact on my writing and how I see the game.

“He often said to me and others over thirty years that the game has no limits,” Willie Steele, Professor of English at Lipscomb University in Nashville, Tenn., wrote to me in an email. “There is no clock keeping time and no boundaries for how far someone can hit the ball.”

—————

“Kinsella spent nearly 20 years working jobs he absolutely hated in order to provide for his family, but he’d harboured aspirations of being a writer that entire time . . .

jobs like a teacher of Creative Writing at the University of Calgary,

which he dubbed ‘Desolate U'”

—————

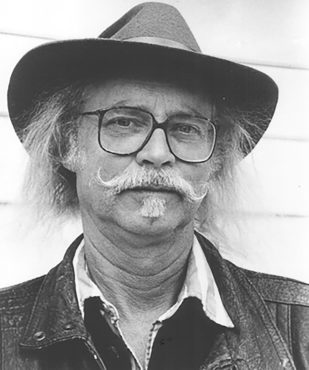

When I contacted Steele, Kinsella’s chief biographer and friend, he had just signed off on the manuscript to Going the Distance with Douglas & McIntyre, his second work on Kinsella, due for publication in 2018. Steele painted Kinsella as a man very much grounded in reality, especially when “compared to the warm-hearted characters in his stories.” He was the antithesis of idealistic Mom-jeaned Kevin Costner in Field of Dreams.

“Bill [Kinsella] was someone who often said he didn’t suffer fools gladly . . . he was very set in his beliefs and wasn’t easily convinced he was wrong about anything. Some of those who knew him for many years have said he was irascible, a curmudgeon, but I found him to be an engaging man who was driven to be a great storyteller,” Steele said.

Kinsella’s journey to acclaimed authordom wasn’t a fairytale either, but a piece-by-piece slog.

Born in Edmonton, Alberta in 1935, William ‘Bill’ Patrick Kinsella’s connection to baseball came through his father, who had a brief career in the minor leagues. William played baseball from age 10; however, he began to gravitate towards writing. At 14, he won a YMCA writing competition, though he was quickly dissuaded from the profession.

“There was a guidance counsellor in high school who discouraged Bill from pursuing writing as a full-time job, treating [it] more like a hobby,” said Steele. “Bill felt this advice led him into years of work he loathed before he decided to attend UVic. He’s spent nearly 20 years working jobs he absolutely hated in order to provide for his family, but he’d harboured aspirations of being a writer that entire time.”

These jobs included working as a civil servant, a salesman, a cab driver, a pizza-parlour manager, and a teacher of Creative Writing at the University of Calgary (which he dubbed “Desolate U”).

Canadian author and Martleteer, W.P. Kinsella. Provided photo by Barbara Turner

“For years, he’d tell people, including students at his former high school in Edmonton, that there was a special place in hell for that counsellor for discouraging a student from pursuing his passion,” said Steele.

Kinsella moved to B.C. in 1967 and earned a B.A. in Creative Writing from the University of Victoria at age 37. He studied under Derk Wynand, Leon Rooke, Alastair Watt, and Bill Valgardson.

“If not for Billy Valgardson helping him hone his craft at UVic in the early 1970s, Bill’s work may never have reached the wide audience it did,” said Steele.

During his time at UVic, Kinsella wrote for the Martlet and penned two features in 1972. His story, “Children of the Cartomancy,” is still on display in the newsroom.

“Bill very much appreciated his time at UVic and writing for the Martlet,” Steele said. “The work with the Martlet afforded him a chance to write a variety of styles and test material out on the audience on a regular basis.”

Until his death, Kinsella kept copies of the Martlet at his home.

At the conclusion of his career, Kinsella had written or co-written 28 books, one published posthumously. In 2015, he received the Order of Canada, and he is the only Canadian to win the Houghton-Mifflin Literary Award.

What, then, made Kinsella’s voice so profound in a sea of American baseball writers?

Kinsella used the magic of baseball language as a vehicle to talk about the hard parts of being human. His short stories, “Barefoot and Pregnant in Des Moines” and “The Baseball Spur,” are painful portraits of disintegrating marriages with baseball serving as a searing reminder of life as they imagined it to be.

Perhaps integral to his success was Kinsella’s aversion to statistical snobbery and play-by-play recalls that exclude the fans that still count on their fingers (myself included). What he captured were those baseball feelings: the searing emptiness of when the season ends and real life resumes. The first time one hears the crack of a wooden bat. The thrill of writing a blank check to baseball (and to writing).

Like a baseballed Alice Munro, Kinsella weaved seemingly insignificant details into his stories — a beehive hairdo, bacon and eggs every lunch — that only become meaningful upon the third or fourth reading, or years after the first. In that way, like Munro’s work, one can grow into Kinsella’s prose.

Then there are his home run quotes, without which no baseball book is complete. “There’s no place lonelier than the minor minor leagues,” Kinsella wrote in “Driving Toward The Moon”; it’s my favourite quote of his. “A ballpark at night is more like a church than a church,” from Shoeless Joe comes a close second.

Then there are his home run quotes, without which no baseball book is complete. “There’s no place lonelier than the minor minor leagues,” Kinsella wrote in “Driving Toward The Moon”; it’s my favourite quote of his. “A ballpark at night is more like a church than a church,” from Shoeless Joe comes a close second.

However, the sassy descriptions of ordinary people who sit at the peripheral of the game are his best. “Her nose was too flat, and her hair looked like she cut it herself to spite someone,” he wrote in “The Baseball Spur.” Then, there’s the portrayal of his host family in “Driving Toward the Moon”: “a middle-aged government clerk, and his wife, also a middle-aged government clerk, are chunky, pale people who might be dressmakers dummies stuffed with porridge.”

“I can still put down some pretty nasty stuff on paper, which is what I enjoy doing,” Kinsella once admitted.

Matching his ability to decipher what to write was Kinsella’s key in navigating the writing industry.

“Bill’s approach to life was to work hard to achieve the goals he had. ” said Steele. “Each year, he would set goals for himself regarding pages written, books published, and so forth. He was absolutely committed to meeting or exceeding the standards he set, and he had little patience for those who only talked about writing rather than sitting down and putting words on a page.”

He treated writing like a business.

“Once Shoeless Joe took off, Bill realized he hit a vein of gold and said he would keep mining that vein until every nugget was taken from it,” said Steele. When he sold the script to Shoeless Joe (for $250 000) Kinsella did not care about how it would be augmented for film.

“Bill told me: stories were like bread. He made the bread, and once it was sold, the bread could be used to make dainty sandwiches for a party or could be torn into chunks and fed to the ducks. As long as he got paid fairly for the story, he didn’t want to be involved with adapting the work to the screen,” said Steele, noting Kinsella was “incredibly happy” with the end result — Field of Dreams.

—————

“There’s magic in baseball. I’ve seen it.”

—————

He did things his way — illustrating to one reporter his contempt for being pushed around. “I don’t carry a gun,” Kinsella told the journalist, “but if some protesters tried to block my car during a demonstration, I’d probably go berserk and shoot them.”

In 1977, Kinsella published Dance Me Outside, a book of short storries narrated by a Silas Ermineskin and about his life on a Northern Ontario reserve that gained a little criticism, but was generally well-received (it was reimagined by Bruce McDonald into a 1994 film of the same name, which received positive reviews).

After Kinsella achieved mainstream success with Shoeless Joe, the critics of his earlier work grew louder. “[They accused] him of ‘cultural appropriation,’ as he was a white man writing in the voice of Cree Indian,” said Steele.

His most vocal critic was Rudy Wiebe, a Canadian author and professor. Provided by Steele, an excerpt from Kinsella’s personal notes on Wiebe shows his disdain. Wiebe, according to Kinsella, was “a sanctimonious, humourless academic, a subsidized writer who’s been eating at the public trough for 30 years, trying to destroy my livelihood.

“I will continue to write whatever I please, about whomever I please, and set my stories anywhere in the world that pleases me, and cheap threats from an academic drone will not change my outlook,” Kinsella said, defending his writing by saying that Indigenous elders were some of his biggest fans of his work.

He was even blunt about his own death, a doctor-assisted suicide in Hope, B.C. on Sept. 16, 2016.

“He essentially told me a couple of weeks ago, ‘You know, I’m not going to be here much longer, so whatever questions you’ve got, let’s get them done,’” Steele told the CBC after his passing.

Despite Kinsella winning awards for his fiction, he often reminded the public that he knew the distinction between fantasy and real life, with baseball somewhere in between; a literacy field where he could play around with endless possibilities.

“Bill often told students to ask ‘what if’ and this case (when writing Shoeless Joe) he asked, “What if a farmer was able to bring Shoeless Joe Jackson back from the dead?’ The story just developed from there,” said Steele.

“Interviewers have tried, always unsuccessfully, to make me admit I believe in the magic I write about,” Kinsella wrote. “I know fiction when I create it. There are no gods. There is no magic”.

Those are hard words for any fan who believes in a man who authors the magic of the game for a living, and, for once, I don’t believe him.

There’s magic in baseball. I’ve seen it.

Every year, players around the world continue to pile into stuffy buses and drive away from their homes having themselves in full with the cheque they wrote to the game as boys.

I’ve long accepted that I’ll spend more on baseball than I’ll ever make in years working in the industry, yet I still show up at the park, following my vocation, that voice—if you build it he will come; anything is possible if you show up. Do it your way.

“Since the foul lines on a baseball field go on forever, there is theoretically no place on earth not covered by a baseball field. The timelessness and lack of boundaries made it possible for anything to happen” said Steele, paraphrasing a metaphor of Kinsella’s.

In The Thrill of a Grass, an older man inspires a community to replace the artificial turf of baseball field with real grass, piece by piece. I read the last passage on a plane — I was far, far away from Iowa, but I could smell the grass.

I was there, for the nuances of baseball are infinite and immeasurable: they’re simply felt.

Slide photo by amer0125 via Flickr