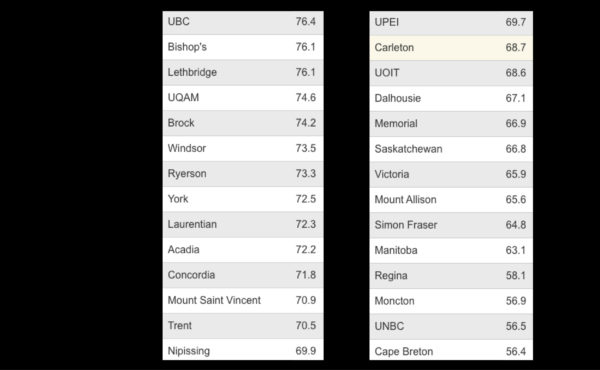

Screenshot via Macleans

Homesickness. Depression. Missing one’s partner. A better program elsewhere. All are valid reasons to leave a university, but none are apparent through statistics alone.

According to a study published by Maclean’s this month, UVic has a 65.9 per cent graduation rate. This percentage is calculated based on the number of full-time students who embarked on their first year at UVic in 2007 and had graduated by 2014 — a seven-year window to complete their undergraduate degree.

With Simon Fraser University sitting just below UVic with their own graduation rate of 64.8 per cent, and the University of British Columbia sitting at 76.4 per cent, Victoria didn’t fare too poorly in the findings — floating at 38 out of 49 universities, somewhere between first-placed Queen’s at 89.5 per cent and last-placed University of Winnipeg at 44.2 per cent.

While university statistics like this are exciting and satisfying by design — providing a definitive number that stamps a ‘good’ and ‘bad’ institution — these studies rarely paint the full picture.

Tony Eder, Executive Director of Academic Resource planning at UVic, explains that B.C.’s transfer system often has a part to play in statistics like this.

“Students in B.C. benefit from a fully articulated transfer system that allows for an almost seamless movement of transfer credit between public post-secondary institutions,” Eder says. “As a result, many students complete their program and degree at a different institution than where they first started. This has always been seen as a successful outcome for students and the system.”

Tristan Wheeler did exactly this. The 21-year-old Wheeler entered the Humanities department in 2015, only to transfer to UBC after one year. UVic, he admitted, was neither his first nor second choice, but, needing to go to university “somewhere,” he enrolled at UVic.

“Leaving was sort of in the back of my mind for the entire first year there,” wrote Wheeler in an email. “My girlfriend was at UBC — which was my first choice — so that was a huge part of my reasoning for leaving UVic.” In general, Wheeler said, UVic “wasn’t really fitted to my personal tastes,” attributing his inability to find his community to the campus’s small size.

“So when the option to transfer to UBC was there, I gladly took it and have had a much better university experience here,” said Wheeler, who now writes for UBC’s student paper, the Ubyssey.

In addition to transferring to another institution, Eder lists more factors that can lower graduation rates. “Students may change their program of study, they may pursue a program not offered at UVic, [or] they may interrupt their studies due to family, financial or other issues.”

Benjamin Bieker, 29, falls into the latter category. Attracted to the UVic campus lifestyle from Calgary, Bieker enrolled in a Bachelor of Arts for Sociology in 2014.

He soon began feeling “overwhelmed” at the lack of direction within his program.

“I didn’t feel job-ready at all, and they kept pushing [and saying,] ‘Oh, get your graduate degree,’” he wrote in an email.

The stress of the program “ignited” a depression that forced Bieker to postpone his studies.

When Bieker attempted to returned to full-time study, he says that a miscommunication between the government funding office and UVic meant he was denied student loans. As a result, he returned to full-time work.

“If you’re at UVic on your own dime, you’re constantly walking a razor’s edge,” Bieker says. “I’m not saying don’t go — just make sure you’re financially prepared.”

For Eder, a single statistic doesn’t show the full picture of whether UVic is a good place for students to complete degrees.

“We would love to retain and graduate every single student we admit if that is in fact the student’s academic and personal goal,” Eder says, “[But] we know that many factors contribute to a student’s decision to stay and complete their degree.”