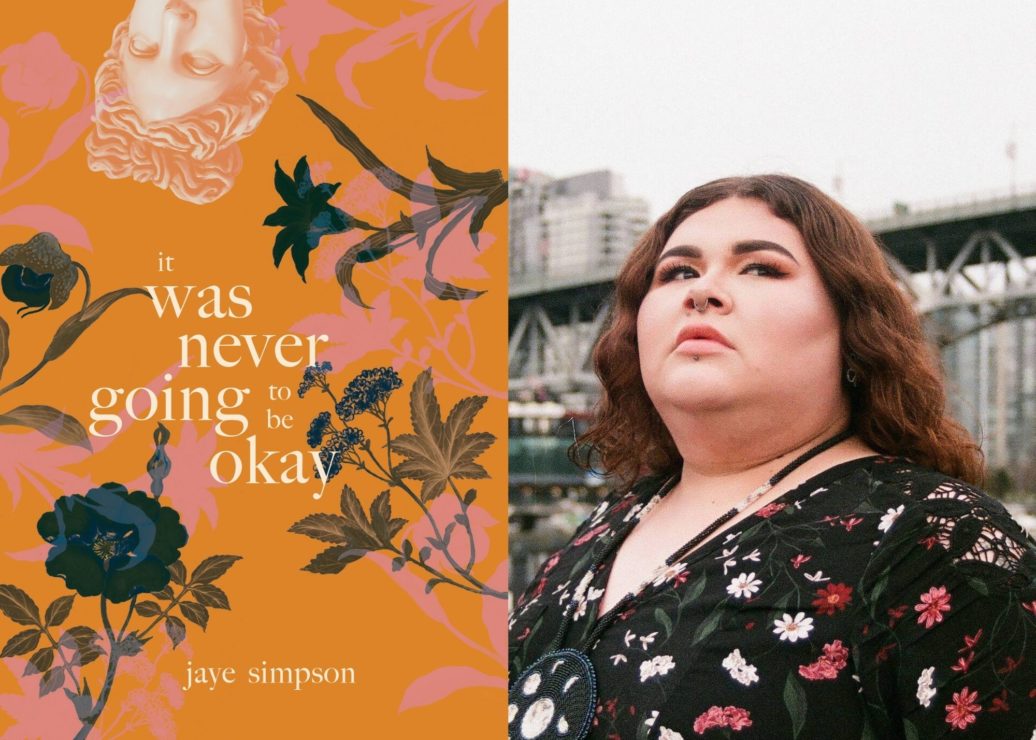

“To think that you’re alone […] is one of the biggest acts of violence that can be done unto you,” says poet jaye simpson. It is a desire to dispel this illusion of loneliness that drives simpson’s first poetry collection, it was never going to be okay.

simpson is an Oji-Cree Saulteaux Two-Spirit nonbinary trans woman whose direct kinship networks hail from the Sapotaweyak, Keeseekoose, and Skownan Cree Nations. they also share both Scottish and French settler ancestry.

Throughout their work, simpson decided not to capitalize their name or their pronouns or “i.” The Martlet chose to do this same in this piece.

“So there’s no capitalization because i don’t think i am that self important…where to me it’s just so tender and it almost invokes a whisper, and i think i wanted to emulate softness and tenderness, in ways I’m not always afforded,” they explained.

Touching on their experiences growing up in foster care, working as a sex worker, and navigating the world of sex, gender, and the erotic, simpson’s poetry explores the complex roles that sexuality, gender identity, and Indigeneity have played in their life.

“i grew up thinking i was the only queer Indigenous person ever because that’s how the system and my experience was designed,” says simpson.

Though simpson claims they are now “unafraid to speak up for [themselves],” they also emphasize that this wasn’t always the case. As part of their mission to call attention to those who have shared similar life experience to them, simpson dedicates it was never going to be okay to “all the queer NDN foster kids out there.”

“It’s just a way for me to say that there are so many of us out there, and also, at the same time, there are so many of us out there that you should be scared.”

For the Sex and Gender Issue, the Martlet spoke to simpson about how their understanding of their own sex and gender factors into their writing, and how it shaped their collection, it was never going to be okay.

CD: Since this is our issue of the Martlet focused on sex and gender, I’d like to ask, how would you describe or define your own sexuality and gender identity?

js: i think very much like my collection of poetry in that regard. i would say very messy, but there’s a softness to it, almost like a bruise, where it’s very tender but it hurts. i always knew i was different […] but labels are such a colonial construct that restrict us more than liberate us, but i understand that at the time being, they’re what we have and that’s a comfort, so i like to say that i identify as a Two-Spirit trans queer non-binary woman but that’s the colonial language […] imposed onto me. So it’s not the language i would like to use but it’s the language i have.

CD: With your collection [it was never going to be okay] that is deeply biographical, was there a catharsis in returning to these various moments throughout your life? Such as your time in foster care, your process of transitioning, and general sexual encounters?

js: Here’s the thing, part of it for sure is catharsis but part of it is PURE pettiness! A hundred per cent is me being like “i’m telling my story. i am no longer going to abide by the weird rules of don’t-talk-about-these-things-that-have-happened.” It’s less about a catharsis of exorcising trauma, that kind of puts the onus on the speaker, and what i’m doing is saying that this has happened to me because of someone else, look at that someone else, who is the one who is enacting that. It’s not about me it’s about the fact that someone who is your neighbour, who is your sister, who is your father, did this. i’m providing a mirror of the fact that some people are consuming this and saying “oh my god, that’s so sad.” Well, you know the person who did this, you know that person.

CD: So along those lines, did the writing of it was never going to be okay, even through this pettiness, and through that turning the mirror back at those who have done wrong, did this process at all help strengthen your sense of queer and Indigenous identity?

js: i would think so, because throughout this process, i’ve had such beautiful kin alongside of me who i developed really strong relationships to, who affirmed me in ways that i’ve been seeking for such a long time…There is definitely a lot of my Indigeneity [throughout the collection] but i don’t force it. i don’t put it in places where it shouldn’t necessarily be as a way to constantly be like, “this is who i am” because my collection speaks it, all of my experiences are an Indigenous experience because i was an Indigenous youth in care. And i am an Indigenous queer person now, so a lot of these have layers and nuances but that doesn’t mean i have to perform Indigeneity to what people perceive. So this collection was definitely a very strengthening experience of how, no matter what i do, i will be who i am.

CD: How did the discovery of the erotic side of your poetry factor into that?

js: Very accidentally. Growing up and coming from some of the places i came from, i found the narrative thing very prudish and uptight at times. And so writing about eroticism was so very new to me. i only really started writing about eroticism two years ago. Very, very fresh, very new.

[…] It’s a way for me to not erase my sexual being, and that i am also a former sex worker so i don’t know why i didn’t write about it. […] Also, desire as a trans woman is so complicated because the currency of our validity is how desired we are in society, which is so awful and so violent and the consumption of us as a fetishized entity is so hard because we are so often a body and never a person. i’m tired of that. So i wanted to write some life into my experiences and my joys but also some of the harder realities.

CD: On a darker note within the erotic writing, I did notice there were repeated images of monsters and beasts and the Godzilla. If you don’t mind me asking, what do these images mean to you and what do they accomplish in the writing?

js: One of the things i am so fascinated with is how their is a horror movie trope of turning all of the monsters to be very queer-coded. When you look at a lot of the monster movies and when there is romance between the monster and the protagonist, it’s so taboo and disgusting, and it’s just an allegory to a queer relationship. When a trans woman begins to be in relationship with other people, we are considered so monstrous. We are so vilified and it happens to almost every queer trans woman and trans woman who’s in cis relationships, it’s just such a pattern.

Where also, as a personal narrative, as someone who refuses to be quiet and refuses to back down, i get the villain edit constantly. i have fought with the ministers of [the Ministry of Children and Family Development], i have fought with some executive directors. i don’t put up with nonsense and so i get vilified really easily. All of these things are saying that i’m a monster but am i a monster? i don’t think so, so i’m a little bit obsessed with the idea of monstrous bodies.

CD:Your introduction to the text […] dedicates the collection to “queer, then you use an abbreviation for Indigenous peoples, foster kids.” This dedication reaches out to individuals who have shared similar experiences to your own. However, many of the poems also play out this dialogue that you mentioned earlier to foster parents, settlers, and previous partners. How would you say your collection balances that relationship between reaching out to those who have shared similar experiences to you, while also having that conversation with those who haven’t?

js: The reason i dedicated it to all the queer NDN foster kids out there is because the purpose of most of this collection is breaking a lot of silence. i speak about very specific circumstances where i really wish i had the strength to speak out in that moment. i’ve done a lot of work with a lot of Indigenous youth in care, some queer, some not, most of them very queer, and in those works, i was unafraid to speak up for myself and for them also. In certain circumstances we have done a lot of advocacy work, and all of them had said they wished they were like me. And part of this is for me to say, “i am like this, but i wasn’t like this the whole time.”

There was a lot of silence and a lot of quiet but also at the same time, in that, i was quiet because i felt like i was forced to [be] […] [this continued silencing] is a pattern, it’s not just me. i grew up thinking i was the only queer Indigenous person ever because thats how the system and my experience was designed. To think that you’re alone, in that sense, is one of the biggest acts of violence that can be done onto you, especially when there are so many! i am so surrounded by queer Indigenous kin, queer Indigenous foster kids, that it blows my childhood mind to think that i am such good friends with these people that we travel Turtle Island together, we spend holidays together, we are in such close relationships to each other, and we understand each other and we laugh with each other.

[being vocal is] just a way for me to say that there are so many of us out there, and also, at the same time, there are so many of us out there that you should be scared. We’re coming back, and we are taking what’s ours, and we are also going to take the back cart that is also due.

This interview has been slightly edited for brevity, punctuation, and clarity.

simpson’s poetry collection (it was never going to be okay) can be purchased here