A new perspective on Bob Wright’s complicated legacy as a developer and business owner

Photo by Sage Blackwell.

Bob Wright died in 2013, but he lives on through the Bob Wright Centre. A drab melange of beige and browns swaddled in brick from the waist down, the building houses UVic’s telescope and the school of Earth and Ocean Science.

Decontextualized from the history of its name, like all buildings on campus, the eponymous Bob Wright Centre owns the character of its title as much as (or more than) its namesake.

For students, it’s rare to think about the people these buildings are named for, yet we often accept that they are named for good reason. One has to have a positive effect on their community, discipline, or field of study to receive the privilege of educational immortality. Right?

Well, maybe not.

In 2007, Bob Wright donated $11 million to UVic — $10 million for the construction of a new Ocean, Earth, and Atmospheric Sciences Building and $1 million in scholarship funds.

Ostensibly concerned about global warming and its oceanic impacts, Wright wanted to invest in scientific research for generations to come.

Graciously accepting the gift, UVic’s then-President David Turpin lauded Wright for his philanthropy.

“Bob Wright’s profound generosity is a true example of how an individual and company can go above and beyond to both support the community in which they operate and contribute to the solution of global issues,” said Turpin in a press release.

But this praise and Wright’s apparent concern for the health of our oceans are only a small part of the building’s legacy. A ruthless businessman, keen developer, and extractive profiteer, Wright’s long career undermines the picture that his association with UVic paints.

Wright the extractive profiteer

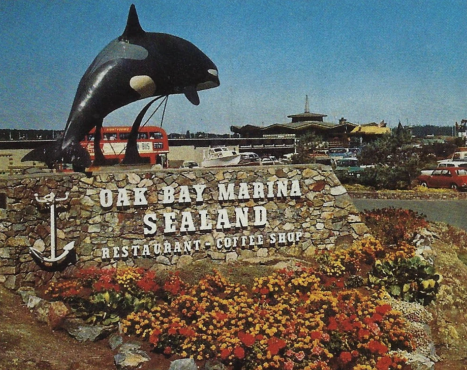

In 1962, Wright founded the Oak Bay Marina and the corresponding Oak Bay Marine Group.

Building on the success of the marina, in 1969 Wright opened Sealand of the Pacific in Oak Bay, known for its headlining orca shows.

Across its 22-year operating period, Sealand housed a total of nine orcas, excluding captive-born calves.

Initially purchasing orcas from competitors, Wright soon sought to source them independently.

Sealand of the Pacific was vying for a top spot among other aquariums, and an orca catch would place it among the best.

Competing Orca capturer and aquarium owner Ted Griffin claimed Wright’s ego would “not be satisfied until he capture[d] a whale.”

In 1970, driven by competitive compulsion and dogged in his pursuit, Wright succeeded in netting four transient orcas in Pedder Bay.

Photo by John F. Colby.

The capture was controversial in Victoria, drawing protest for the seeming lack of governmental oversight on a morally dubious business pursuit. Moreover, one of these four transients was a locally recognized white orca. Wright was an island Ahab.

UVic’s chancellor at the time, Roderick Haig-Brown supported Wright’s actions, arguing that the display of captured orcas humanized ‘killer whales’ in the eye of the public. Similarly, Tsawout chief Ed Underwood congratulated Wright on his capture of the all-white orca, recognizing it as a sign of good fortune for the entrepreneur.

Ironically, it would not be long until Tsawout leadership opposed Wright on his proposal to develop the Saanichton Bay Marina on W̱SÁNEĆ fishing grounds.

After capturing the orcas, Wright refused to provide trainer-requested medical aid to the Pedder Bay quartet during transport. On other occasions, his reluctance to pay for humane treatment measures resulted in similar suffering, such as improper transport equipment and medical aid.

Malnourished and stuck in sea-pen limbo, one of the four orcas drowned before it could be transferred. Wright ordered a quick and discreet disposal of the carcass. Sealand divers towed the whale’s corpse out of Pedder Bay under the cover of night, weighted her body, and sunk her below the depths she once called home.

Jason Colby, UVic history department chair and author of Orca: How We Came to Know and Love the Ocean’s Greatest Predator, says on the topics of Wright and his treatment of animals, “When push came to shove, he prioritized making profit.”

“I think he really did have passion for the sea and for its creatures, on one level,” says Colby. “On another level, he was ruthless with competitors and could be pretty cold blooded, cold-hearted about the impact on animals that his venture had. I think Sealand’s a pretty good example of that.”

Although the infamous film Blackfish came out long after Sealand went defunct, Colby says the story starts in Sealand with Bob Wright. Tilikum, the subject of the documentary, was in captivity there for seven years.

Photo by Ocean Echoes via VictoriaWiki.ca.

Outside of his ventures with Sealand, Wright also facilitated global live orca sales through what Colby calls a “shadow subsidiary” named BoLan. His desire to profit off the lives of orcas had outgrown the capacities of the public-facing Sealand of the Pacific.

Emphasizing that Wright’s modus operandi was profit maximization, Colby tells me that “Wright never showed evidence that he was driven fundamentally by a love for animals or a desire to connect with them.”

However, there is evidence that orcas were not the only ones endangered by their captivity at Wright’s Sealand.

Sealand of the Pacific ultimately closed in 1991 after the death of 21-year-old UVic marine biology student and part-time Sealand Orca trainer Keltie Byrnes. Byrnes slipped into the pool post-show and orcas Tilikum, Nootka IV, and Haida II held her underwater until she drowned. The Orca trio was then sold to U.S.-based Seaworld, where they have all since deceased.

Later, former-trainer Eric Walters claimed that Sealand animals were often underfed in order to increase the value of food as a performance incentive, speculating that this treatment may have factored into the orca’s aggressive behavior.

At the same time that Wright was making waves offshore in his conflict with the island’s orca population, his swelling development empire clashed directly with communities long-tied to the land Oak Bay Marine Group sought to monetize.

Wright the developer

The proposed Saanichton Bay Marina pitted Wright and developer George Wheaton (who also has a UVic bursary in his namesake) against the Tsawout first nation.

Proposed in 1974, the 1256-berth marina would encroach on traditional food sources for the W̱SÁNEĆ people, who have fished the bay since time immemorial. The battle over the bay would unfold for over a decade. Famously, Tsawout member Earl Claxton Jr. protested the marina development by clinging to a sea-faring dredge bucket for over an hour in a freezing snowstorm to prevent early-phase construction.

In 1987, the B.C. Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Tsawout nation, rendering Wright’s development dreams for the bay null.

Wright the business-minded fisherman

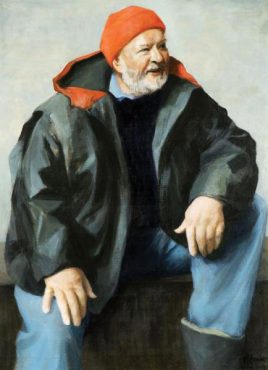

Throughout development roadblocks and tragedy at Sealand, Wright found joy in his maritime hobbies. A self-described “gumboot fisherman,” Wright’s true passion was sportfishing.

Bob Wright. Photo via UVic.ca.

This passion was made financially lucrative by Oak Bay Marine Group’s establishment of a number of fishing lodges along the coast of British Columbia, one of which was the Charlotte Princess boat located at Langara Island in Haida Gwaii.

This lodge brought the Oak Bay Marine Group into direct conflict with the Haida nation in the early 1990’s.

Anchored in Duu Guusd heritage site/conservancy, the fishing lodge was in close proximity to a number of important Haida cultural sites.

Amid growing concerns that sportfishing businesses were outcompeting Haida commercial fishing operations and impeding on Haida land and fishing rights by diminishing salmon and halibut stocks, the local Haida government sought to implement a two per cent tax on fishing lodges. This tax would fund catch-monitoring programs and assert Indigenous rights. This protectionist measure reflected a significant effort by the Council of the Haida Nation to protect local economies and stave off predatory development.

Oak Bay Marine Group, however, refused to pay the tax, and in the summer of 1991, tensions came to a head. Haida canoes and commercial watercraft blocked the bay where the resort sheltered, preventing seaplanes from delivering customers to the lodge.

In response, Oak Bay Marine Group obtained an injunction restraining the defendants (the Haida) from “impeding the plaintiffs commercial sports fishing operation.”

In a 1991 conversation with the RCMP, Haida Nation member Ernie Collison made his feelings towards Wright’s presence in Haida Gwaii clear: “What we want is for Mr. Wright to pull that anchor on the boat and just get out of here and stay away. He is not welcome here anymore.”

Moving forward from Wright’s legacy

So what does all this history mean for the Bob Wright Centre?

“It was pretty clear he was looking for ways to burnish his legacy,” says Colby. The naming of the Bob Wright Centre “creates an association in people’s minds that’s pretty different from the people that lived through that time.”

Colby himself struggles to condemn or endorse Wright’s contribution to UVic. “I found myself conflicted when that happened,” he recalls, recognizing that Wright didn’t have to give the money to UVic, and in doing so, history aside, he did a good thing. However, Colby says, “It’s incumbent on a university to not accept uncritically the narrative that would whitewash the donor’s meaning and legacy.”

The Martlet reached out to UVic about what Wright’s legacy means for the building and the wider institution. The university declined to comment.

UVic Associate Librarian, Reconciliation Ry Moran, however, doesn’t mince words when contextualizing Wright’s legacy in B.C. Moran charts out the province’s history across two tracks: Indigenous land and culture protectionism (and eventual decolonization), and colonial exploitation. He places Wright on the latter.

For Moran, questioning Wright’s past is one of the few things we can do. “While the past has happened and can’t be changed, what we can change is what we know about the past,” he says.

Moran also says that “being hyper-aware of the local is actually a very important path to decolonization,” emphasizing that an inquisitive view of the space around us is essential.

“Right now society is going through a moment of realization that brings into light multiple perspectives on historical figures, statues, place names that are on public infrastructure,” Moran tells me. “This moment should be celebrated because … we are placing greater weight on the diversity of voices we are listening to.”

Wright is just one node in this moment of realization, but at the local level he is an important one. Described by the Times Colonist as a “visionary entrepreneur” and a “born leader” and dreamer by Oak Bay News, Wright is most commonly remembered as a salt of the earth businessman and keen philanthropist. UVic has an opportunity to make our recollection of Wright and his impact on Island communities and oceans more fulsome.

While Wright’s donation to UVic certainly helps students, it cannot be accepted without recognition of its baggage in tow. Let the message be clear; one’s place in history is not for sale.

As Moran has reminded us, our “histories might be wrong, but we can remember them right.”