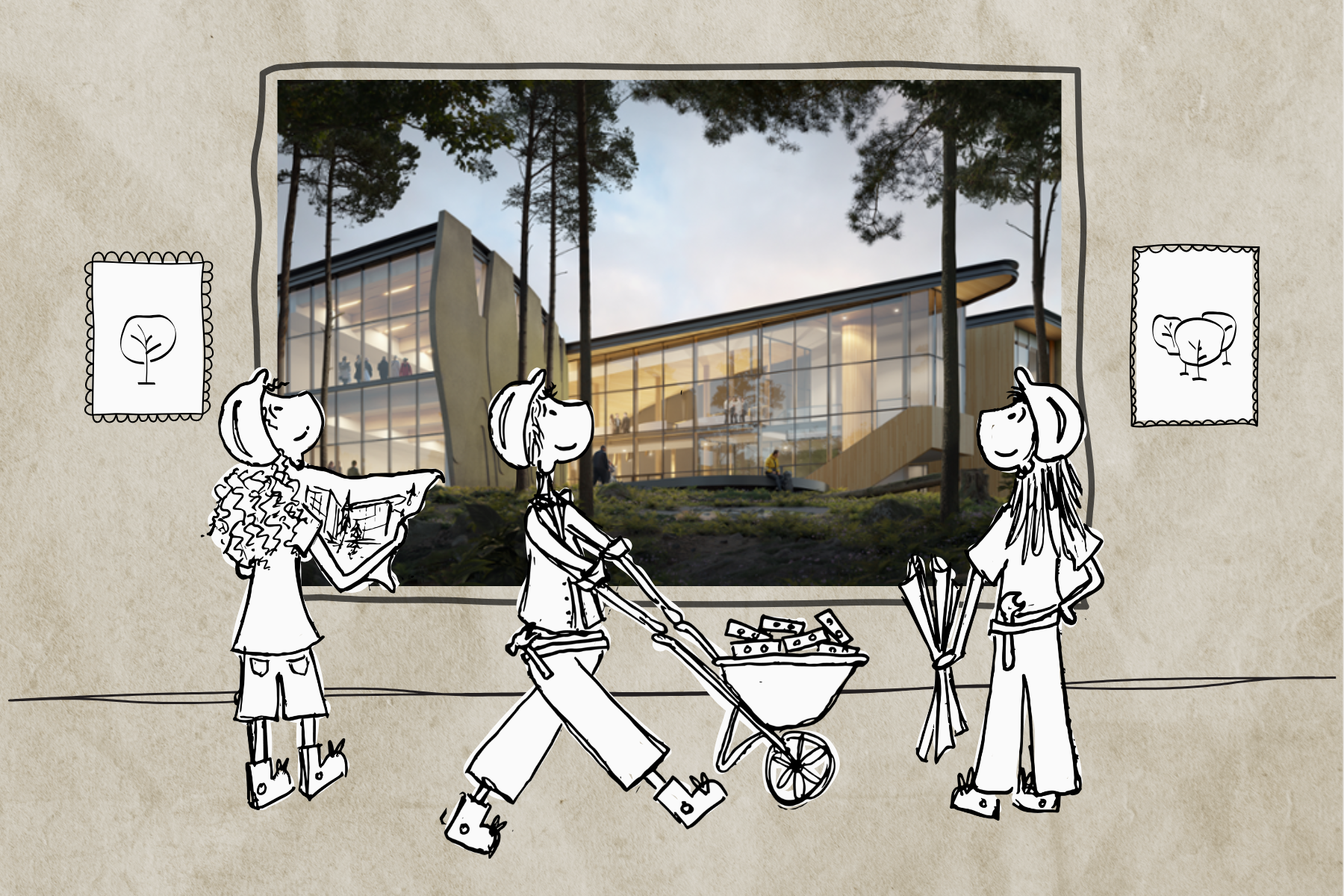

Ten years of planning went into a new 2 440 square-metre wing of the Fraser Building

Illustration by Sage Blackwell, rendering via the University of Victoria.

A new wing has been created in the Fraser Building to house a Centre for Indigenous Laws (CIL). Starting in September, it will be used as a new space for the University of Victoria Joint Degree Program in Canadian Common Law and Indigenous Legal Orders (JD/JID), the Juris Doctor (JD) program, and other legal centres such as the Indigenous Law Research Unit, the Environmental Law Centre, and the Access to Justice Centre for Excellence (ACE).

Additionally, the new wing will house public legal education programs and the Business Law Clinic.

Indigenous-led Design

The design of the CIL was actualized through a long engagement process with Elders and members of the Songhees, Esquimalt and W̱SÁNEĆ communities, as well as Elders who work with the university’s Office of Indigenous and Academic Community Engagement.

The new wing received the 2023 Canadian Architect Award of Excellence, due to its Coast Salish design elements and its focus on bringing the surrounding forest into the building. The architectural design was led by Two Row Architect — an Indigenous-owned firm — in partnership with Teeple Architects Inc. and Low Hammond Rowe Architects.

Identified as a key project goal in the planning of the new wing was a design that blurs the boundaries between the indoors and outdoors, to further foster the value of respect for the environment and to honour and interact with nature.

In an interview with the Martlet, Juliet Van Vliet, a Campus Planner at the UVic Office of Campus Planning and Sustainability, offered insight into the planning and design process, which began in 2015.

“In my line of work I believe in environmental determinism — that what’s in your environment shapes how you feel … how you respond, and how you act. I believe that this building will support students in the study of law to find inspiration in the natural environment and the Coast Salish stories that are woven into the design of the building.”

She told the Martlet that the project schedule had time built into it for the architect to engage with Indigenous Knowledge Keepers on the lands and on the waters, to hear stories which then informed the design of the building. In total, 13 ideas derived from stories shared by Coast Salish community members were translated into architectural design concepts.

Every phase of the process was adapted based on “feedback heard from Indigenous community members, from Indigenous architects, to Indigenous faculty and staff,” Van Vliet said, describing her role in the project as one of “learning and support.”

From the amount of sun and shade, the shapes in the walls, where the outdoors were visible, and what the different spaces are used for, everything in the new wing “has a story,” Van Vliet said. “Every detail in the building was so carefully considered.”

Two design features of the building include a stormwater system and an Elders’ garden. The stormwater system was, “designed to tell the story of water on the landscape,” Van Vliet told the Martlet, while the Elders’ garden was “designed both as a learning space outdoors and for harvesting for different ceremony needs.”

The plants in the Elders’ garden are intended for both ceremonial use for Elders, and for learning in a more intimate outdoor setting. The specific plants were “chosen based on what Elders need for ceremony regularly, so that they are easily accessible to Elders from their dedicated work spaces in the building.”

Large and small gathering spaces are also found within the wing to accommodate a range of legal practices.

An Indigenous community member shared a story with Van Vliet regarding the Fraser Building prior to the new wing. They shared a photo of their family member, who was studying in the JD/JID program, standing in front of the building. According to Van Vliet, the community member pointed out to her that the building looked very “institutional, and not very comfortable.”

“I’m really hopeful that … this building can feel comfortable and be a source of inspiration and perhaps a source of pride for students that attend there and for their families back home.”

The JD/JID Program

The JD/JID program has been offered at UVic since 2018, and was the world first joint degree in Indigenous legal orders and Canadian common law. Students graduate in four years with two professional degrees: Juris Doctor (JD) and Juris Indigenarum Doctor (JID). The program was developed by two of Canada’s leading Indigenous scholars: John Borrows, Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Law, and Val Napoleon, Law Foundation Chair in Aboriginal Justice and Governance.

Each year in September, The JD/JID program intakes a class of 25 students and aims to have a minimum of 50 per cent of each class composed of Indigenous students.

The Martlet interviewed Andrew Ambers, a third year student in the JD/JID program, to learn about his time in the program. Ambers is Kwakwaka’wakw from the ‘Namgis and Ma’amtagila First Nations. He previously completed his Bachelor of Arts (Hons.) in political science and Indigenous studies at UVic. Ambers is also an Indigenous internationalism research fellow at UVic.

His undergraduate degree in Indigenous studies and political science introduced him to both “Indigenous Peoples’ own laws and politics” and “state legal processes,” Ambers told the Martlet. He noted that UVic is “uniquely situated with Indigenous faculty that represent diverse Nations” and that this exposure guided his path into the JD/JID program.

The Martlet asked Ambers what the JD/JID program aims to prepare students for.

“The program … reflects and responds to the reality that every part of Canada is subject not only to the laws of the federal government, provinces, and municipalities, but also the laws of Indigenous Nations.”

He said that the JD/JID program is grounded in this reality, and prepares students and future lawyers to work across these legal systems and overcome conflicts where they might arise. To further articulate how the JD/JID program prepares students to engage with various legal systems, he recalled a gathering from last summer.

Photo by Desiree Wallace.

“Ma’amtagila is a First Nation of the Kwakwaka’wakw, and its territories include Northeastern portions of Vancouver Island, the waters that are generally known as the Johnstone Strait, and extend into the adjacent islands and lands. So with that grounding of … where my Nation comes from, recently the Ma’amtagila hosted a gathering and ceremony at our village of Hiladi, which means ‘the place to make things right.’”

“At this gathering … songs and dances were shared along with our histories. This included a Declaration of Sovereignty to affirm Ma’amtagila law and rights. This Declaration addressed the roots of Ma’amtagila law: land, water, air, youth, Elders, Matriarchs, and Chiefs.”

Ambers said that it was not a private gathering, but the Ma’amtagila hosted Indigenous and institutional representatives from across the globe to act as witnesses — from Harvard, the University of Chicago, the University of British Columbia, University of Victoria, Ecojustice Canada, and Indigenous Nations across South and North America.

“By engaging with and witnessing our law and governance,” Ambers told the Martlet, “those present at the gathering have responsibilities to bring what they witnessed with them into their diverse worlds to make things right — creating a standard of justice that guides how to live lawfully. This is the nature of Indigenous law for our people: sharing our culture, law, and worldview to honour the truth.”

Ambers said that this Declaration reflects the foundation of the JD/JID program, which is that there are multiple legal systems that apply at the same time in any given territory. “For the Ma’amtagila, the Declaration recognizes the importance of Canadian law,” he told the Martlet, “while also making things right by placing Indigenous law on the land where it has otherwise been wrongfully displaced.”

“As a coastal First Nation, Ma’amtagila holds important rights to land, submerged land, water, air, and resources. The Declaration is a dual application of Indigenous — in this case Ma’amtagila — law, and Canadian law, in the sense of we’re articulating our ways of life and principles in a way that is concurrently relevant to the law of our people and the law of Canada.”

In his own work, one of Ambers’ focuses is how water governance in Canada interacts with coastal Indigenous legal orders.

Ambers told the Martlet that Indigenous Nations on Vancouver Island and across the west coast of B.C. share a unique history in Canada while maintaining independent cultures, laws, and practices.

“Among coastal First Nations, there are significant relationships with waters,” Ambers said, “including through occupying oceans by canoeing, fishing, navigating, and enhancing productivity of aquatic species. I have yet to see the unique maritime cultures of coastal First Nations be adequately reflected in the rights of Indigenous Nations under Canadian law. This is part of the work to come.”

Ambers shared one of his favourite experiences in the JD/JID program so far, which was a trip two years ago that his cohort did to Cowichan Tribes’ territories. He recalled that they hiked Mount Tzouhalem with a Knowledge Holder and Dr. Sarah Morales, the director of the JD/JID program and a member of Cowichan Tribes.

“We hiked up and … would stop and listen to different stories and laws, and draw out principals. This has informed a lot of the work that we have done with other Coast Salish law-related matters in the program,” said Ambers.

“I think that this has been a significant experience for a lot of people in our cohort … and a really informative way of learning Coast Salish laws on Coast Salish lands,” he said.

In terms of the new Fraser Building expansion, and having his classes moved there in the fall, Ambers said that he is most excited for having a space for “communities to come in and use it for different matters — from resolving disputes to … starting to articulate their laws in a different way or continuing to articulate their laws.”

Ambers noted that the Centre for Indigenous Laws “will enable Nations to rebuild their legal orders, express their laws, resolve disputes if there are any, build relationships across Nations, and work together to strategize a path forward –– something that Indigenous Nations have always done by working together and across difference.”

Cutting-edge Work at The Indigenous Law Research Unit

Also housed in the CIL is the Indigenous Law Research Unit (ILRU), the only dedicated research centre on Indigenous law in Canada. The Martlet spoke with representatives, Brooke Edmonds, Jessica Asch, and Tara Williamson to learn more about their work.

Edmonds, of Te Whānau ā Apanui, Ngāti Porou, and European descent, has been ILRU’s Coordinator since 2019. She is also the lead for outreach, communications and publications, and she facilitates workshops and presentations as part of ILRU’s projects, and in the broader community. A UVic alumna, she graduated with honours from the faculty of Art History and Visual Studies.

Asch is a settler of Jewish and Irish ancestry, and became Research Director at ILRU in 2015, and has been Co-Research Director since 2021. She oversees its collaborative, community-based legal research and public legal education projects. She is currently completing her Master of Laws at the UVic Faculty of Law.

Williamson has been a Co-Research Director at the ILRU since 2021. Williamson is a member of the Opaskwayak Cree Nation and also has close family ties to Beardy’s-Okemasis in Saskatchewan as well as an adopted member in the House of Dhadhiyasila of the Haíɫzaqv Nation. She holds degrees in social work, law, and Indigenous governance and she has been a professor and instructor at many universities including UVic.

In a collective statement to the Martlet, they said.“The Indigenous Law Research Unit (ILRU) began as a national research project at UVic’s Faculty of Law in 2012. The project was done in partnership with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, the Indigenous Bar Association, and was funded by the Law Foundation of Ontario.”

“The project ultimately identified a large demand for Indigenous law research for the purposes of law revitalization and implementation,” they stated, “and ILRU emerged from this project as an organization in response to this demand. Since that time, we have worked with dozens of community partners — at their request — and hundreds of community members.”

Their purpose is to “take up, by invitation, the critical Indigenous legal questions that come from communities and to co-create the practical and accessible resources to address some of the challenges they face today.”

Edmonds, Asch, and Williamson said that the new wing will help them align with their principles of working “collectively, collaboratively, and in community.” They are particularly excited that their office, and the wing as a whole, has been designed to be welcoming, and includes gathering spaces for community partners, students, staff, and faculty.

“In the last year, ILRU received 66 requests to build partnerships and support Indigenous law work, and it will be fantastic to now have a place to host meetings and build relationships when we get invitations to work alongside potential partners.”

“One of the biggest challenges of being in a university setting is that the institutional environment can be intimidating for people outside the university community,” they stated, “and for work like ours, which focuses largely on supporting the work of Indigenous communities outside of UVic, it is important for us to have spaces that are welcoming and inviting for guests and community partners. This was a challenge for us before the expansion, as our offices were tucked away upstairs in the law library, which deterred many visitors.”

They said that the culturally appropriate design of the new wing and abundance of space “will make the law school more welcoming and inviting of the questions that matter to Indigenous nations and communities.”

“Our legal research and public legal education projects are shaped in collaboration with Indigenous community partners and are informed by their territories. Because of this orientation, it is important to us that the art, laws, and cultures of the Lək̓ʷəŋən and W̱SÁNEĆ nations and peoples, on which and near where UVic now sits, were centred in design of the building as part of a collaborative process, and that the natural world around the expansion was cared for and considered in the build.”

Two projects that the ILRU team are excited to publish soon on their website are a project with Cowichan Tribes on Quw’utsun Water Laws — “a 250 page final report…a Casebook of more than 20 Cowichan stories, and appendices of historical and contemporary practices of water law intervention”, and a project regarding Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in human rights laws — “centering a Dënezhu legal understanding of human rights.” Current work that they are passionate about is a recent trip to χʷɛmaɬkʷu (Homalco) territory, where they conducted an Indigenous laws workshop and did land-based learning as a team.

They also highlighted their partnership with Qwelmínte Secwépemc (QS) to support the implementation of Secwépemc law in the context of their legal and educational work. Further resources and descriptions of many of ILRU’s projects can be found on their website.

The Environmental Law Centre and The Access to Justice Centre for Excellence

The Environmental Law Centre (ELC) is a non-profit society that partners with UVic’s Faculty of Law to deliver a clinical program in public interest environmental law. They provide legal aid, legal research, and legal education services to Indigenous, environmental, and community organizations as well as individuals across B.C. More information can be found on their website.

The ELC has spent the past several years in temporary spaces, and a spokesperson from the ELC confirmed that their staff are very excited to move into their new home in the Fraser Building expansion. According to the spokesperson, they look forward to having offices close to one other, as well as having access to meeting rooms where they can “gather in person to collaborate as staff, with students, and with our clients.”

Similarly, a spokesperson from the The Access to Justice Centre for Excellence

(ACE) recalled how their staff have “worked off the sides of professors’ desks, bouncing between the virtual sphere and temporary, windowless rooms in the Faculty of Law”.

“Remarkably, ACE has achieved significant growth despite these constraints. In the past five years, it has evolved into a provincial centre, with members from each of BC’s major research universities, working across the disciplines of law, public administration, criminology, public health, and data science,” the spokesperson said.

The spokesperson told the Martlet that their new base in the CIL will support ACE’s ability to build “robust, interdisciplinary research on Canada’s access to justice crisis” and will enable ACE members to “host community partners, engage graduate students, and advance major initiatives, including ambitious research now being planned for the study of legal capabilities and the evaluation of dispute resolution design models.”

After ten years in the making, UVic’s Centre for Indigenous Laws will soon be up and running. It will support the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s (TRC) Call to Action #50, which aims to to establish “Indigenous law institutes for the development, use and understanding of Indigenous laws and access to justice, in accordance with the unique cultures of Aboriginal peoples in Canada,”

Additionally it is tied to Calls to Action #27 and #28, which call for lawyers to be trained in “intercultural competency, conflict resolution, human rights, and anti-racism,” and learn the history and legacy of residential schools, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Treaties and Aboriginal rights, Indigenous law, and Aboriginal–Crown relations, respectively.

The construction of the CIL is an important step towards these calls to action. As Ambers said in his interview, “the JD/JID program is about fostering possibilities of a more legal and lawful future in Canada.”