During the renaissance, before medicine was all that reliable, an important concept in the western world was the Ars Moriendi, or “the art of dying.” Because death was always an imminent thing, it was considered essential to know how to “die well.” What that entailed was somewhat outside the scope of what we now think of as palliative care. We’re talking about dying not only with all worldly and spiritual accounts settled, but as the culmination of a well-lived life. The goal was to leave this life with dignity and fearlessness, and maybe even style.

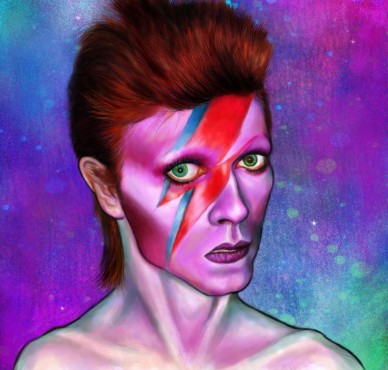

David Bowie, of course, was the king of style. His personas from the ‘70s are beyond iconic; they’re cultural touchstones. With his passing, though, we’ve been given a stunning reminder that Bowie was also a serious artist. His longtime producer Tony Visconti made headlines for his remark about Bowie’s deliberately timed final album: “His death was not different from his life — a work of Art. He made Blackstar for us, his parting gift.”

Now, if you think it’s a stretch that Bowie had the Ars Moriendi in mind as a context for his final album, bear in mind that its second track, “’Tis a Pity She Was a Whore,” references an obscure 17th-century tragedy. Or, look further still and you’ll see that Bowie once indignantly put to rest the suggestion that the cover of Heroes referenced German expressionist Walter Grammaté, who he deemed “wishy washy,” affirming it was rather Erich Heckel’s 1917 painting Roquairol. The man knew his history. He had an eye on culture, past and present, that was keener than any other.

As Arcade Fire’s Win Butler wrote in his memorial, Bowie was “a true artist.” The reason that artistry is a downplayed side of his legacy is that he was seemingly so unpretentious, so cool, so charismatic, even as his rock ‘n’ roll was often simultaneously art with a capital A. It’s this that assured him such an enormous audience; Bowie was never unrelatable, even when he was bizarre. His music will continue to play on rotation over grocery store speakers as well as in the headphones of edgy art school students. Bowie mastered that dichotomy.

He also never took himself all too seriously. In a 2006 episode of Extras he played a bizarre version of David Bowie: sitting at the piano at a party, he improvises a sinister and hilarious tune at Andy Millman’s (Ricky Gervais) expense. Then there was his unforgettable turn as Jareth the Goblin King in 1986’s Labyrinth, where he danced and sang alongside an ensemble of puppets, maybe the only man on earth who could do so and still look impressive and magical. These are just some of the asides in his career that prove the breadth of his skill as an entertainer.

So, while the much-discussed “Lazarus” video makes up one side of David Bowie’s artful passing, with its bold and unflinching dramatization of his death, the video for Blackstar’s title track shows another side of him. It’s willfully impenetrable, symbolic and strange, invoking the oddball sci-fi of Major Tom and Ziggy Stardust, playing on crucifixion and preacher imagery, featuring hallucinatory rituals, even possible echoes of T.S. Eliot’s “The Hollow Men.” I think it’s a better representation of Bowie the artist: energetic, perplexing, playful, fascinating.