UVic Board of Governors approves EQHR report recapping and analyzing a year of the new policy

The Michael Williams Building, where UVic’s Board of Governors approved an EQHR report recapping one year of their sexualized violence policy. Photo by Belle White, Photo Editor

The University of Victoria’s Board of Governors approved the office of Equity and Human Rights (EQHR)’s annual report at their May meeting, which contained the first publicly available peek into the progress of UVic’s Sexualized Violence Prevention and Response Policy (SVPRP) since it was officially adopted in May 2017.

“The plan is that every year for the report, we’ll be summarizing the work that has been done and the work that we’re in the process of doing,” said Leah Shumka, the Sexualized Violence Education and Prevention Coordinator at UVic — a position created by the SVPRP to oversee its implementation. Future progress reports will be provided each September, starting in 2019.

For those who don’t want to dig for the report—nestled 185 pages deep in the Board of Governors meeting docket and linked here for all you jargon-loving purists —we’ve recapped the highlights below.

Statistics

Since the policy was created, four formal reports have been made — one will be investigated under UVic’s Discrimination and Harassment Policy, and the others have been or currently are under investigation in accordance with the SVPRP. When a report moves into an investigation, Shumka said that UVic often hires third-party investigators trained in trauma-informed and survivor-centered practices to conduct investigations into those reports.

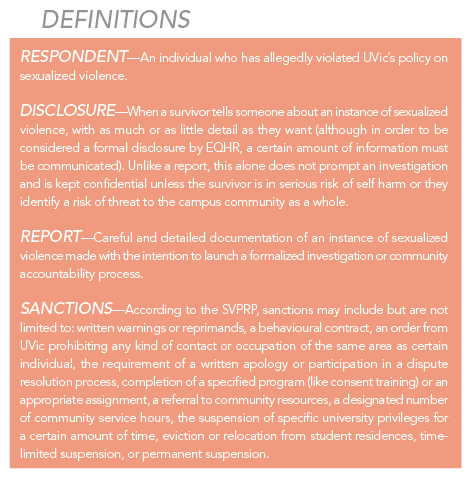

At the time of writing this year’s EQHR report, two investigations were completed and found that the policy was violated. The report states that UVic imposed “minor sanctions” in both cases — which, according to the policy, may see the respondent receive penalties including a written warning, behavioural and university access restrictions, community service hours, or mandatory participation in a restitution process, as deemed appropriate by UVic President Jamie Cassels.

In order to be numerically counted by EQHR, formal disclosures of sexualized violence must be communicated to their offices, either directly or through Campus Security, the Office of Student Life, or Residence Services. The report acknowledges that there are many more incidences of sexualized violence than it is able to depict, due to the limitations of formal counting procedures required to collect reliable data.

Overall, the impact on survivors was generally perceived to be significant by EQHR.

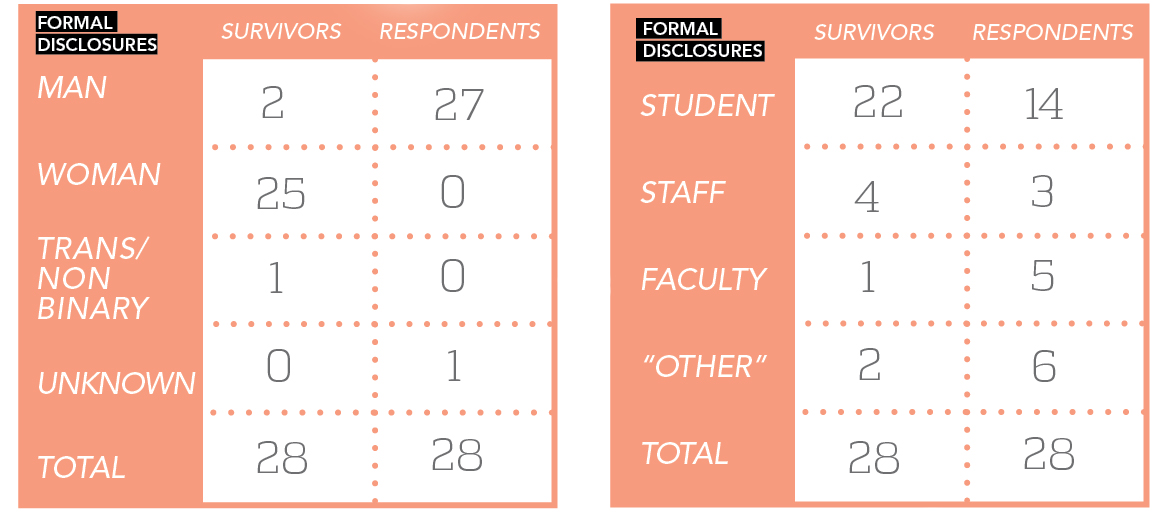

Under those conditions, 28 total formal disclosures were made by 22 students, four staff members, one faculty member, and two individuals listed as “others” by the official report — a classification that includes community members, alumni, and people whose identity is unknown. Of the alleged respondents in these disclosures, there were 14 students, three staff members, five faculty members, and six “others.”

So far, no disclosures have required an emergency health or safety response.

Out of 28 survivors, 25 identified as women, two identified as men, and one as transgender or gender non-binary. For the alleged respondents, 27 identified as men, one was unknown, and none were identified as either women, transgender, or gender non-binary.

However, the report was unable to break down the specific population statistics further — in areas like nationality, graduate level, and departments — due to a relatively low number of survivors and respondents. Shumka said this was done in the best interest of survivors, since “once the numbers get too low . . . we’re potentially going to compromise confidentiality.”

A breakdown of formal disclosures made under UVic’s new sexualized violence policy this year. One survivor counted for two categories. Data via UVic

At least half of the formally disclosed incidents consisted of unwanted sexualized attention: sexualized looks, jokes, comments, and come-ons.

“Despite being non-physical in nature these incidents were, in some cases, extremely harmful,” the report said, especially when the respondent held a degree of power or control over the survivor or exhibited aggressive and persistent behaviour.

Other survivors described incidents that constitute sexual assault level one, which is defined under the Canadian criminal code as non-consensual sexual touching or bodily contact that may involve minor physical injuries to the survivor.

Overall, the impact on survivors was generally perceived to be significant by EQHR.

“Survivors described a range of mental health concerns including depression, anxiety, and stress, which were sometimes acute and required immediate mental health support,” the report said. “They also described difficulties focusing on their academic and professional responsibilities, the impact on personal and professional relationships, and a loss of trust and faith in individuals and systems.”

UVic found that they had jurisdiction over 15 out of the 28 disclosures or reports recorded since the policy took effect, with the jurisdiction of a single case unknown. Two of the incidents under UVic’s jurisdiction occurred over two or more years ago, which is classified as historical.

Implementation and education

A primary focus for EQHR over the last year has been educating the campus on the SVPRP’s core principles and expectations, especially in how they apply to each member of the UVic community. Shumka oversaw the creation of a workshop to provide people with an overview of the policy, and has held 39 presentations and workshops ranging from 30 minutes to three hours, with close to 1 100 attendees to date.

“The feedback from these workshops has been overwhelmingly positive and demand for these workshops continues to grow,” the report said.

Additionally, Shumka has developed three informative brochures about the policy aimed at faculty and staff: “Sexualized Violence Prevention and Policy: An Overview,” “How to Receive a Disclosure,” and “Consent and Respect.”

Everyone who has come to the intake office for a confidential consultation or disclosure has received information on their options regarding the policy and resources for support both on and off campus.

Looking forward

Implementation has required the collaboration of many departments, and is intended to be an ongoing process as the SVPRP is reviewed and further developed to reflect additional nuance.

“We continue to refine the processes to ensure that they are survivor-centred and trauma-informed, and to encourage more individuals to come forward and make formal disclosures and avail themselves of the supports available,” said the report.

Shumka is in the process of developing two versions of a student-focused workshop, to be available both online and with peer facilitators, that she aims to have completed for fall orientation and pre-arrival activities.

Thirty-nine presentations and workshops ranging from 30 minutes to three hours have been held, with close to 1 100 attendees to date.

Also in the works is an eight-week men’s program, consent training tailored for international students, a new website, a slew of prevention-orientated marketing and campaign materials, and continued work on a three-year education program to address the root causes of sexualized violence.

Over the summer, the policy will undergo an administrative and systems review involving the collaborating campus departments and other groups deemed appropriate.

“We approach these changes as we approach all of our work, with humility and a commitment to learn from those who have done the work before us,” Shumka said.