Williams is still coaching, despite at least 17 known allegations, a pending lawsuit from a former Vikes athlete, and an alumni letter calling for more action from UVic

By spring 2019, three Vikes women’s rowers and one assistant coach had filed formal complaints alleging head coach Barney Williams was abusive. UVic’s investigation into these claims that followed was based on a policy that does not contain a definition for “abuse” — or the words “sport,” “coach,” or “athlete.”

In total, at least 17 individuals have either formally complained or spoke to the press with allegations against Williams. In addition to the four individuals who formally complained, nine rowers alleged abuse in Natasha Simpson’s original Martlet article or to Laura Kane at the Canadian Press. Three Cornell University rowers and one athlete from the “Row to the Podium” program, all of whom were previously coached by Williams, also came forward to Kane.

Athletes allege they were forced to train while injured, pushed to return to practice when sick, publicly berated, pitted against their teammates, and suffered aggravated mental health issues.

UVic says they have developed a set of initiatives to support their varsity athletes and added two prominent mentors to support their rowing program. Williams is also participating in professional development programs that focus on conflict resolution and communication. He continues to coach the women’s rowing team, and provided an email statement to the Martlet.

“I regard it as my primary responsibility to create a safe and rewarding experience for every member of the roster and was and remain deeply sorry to learn that this was not the experience for certain members of the roster during my first season,” Williams said.

A group of over 60 Vikes rowing alumni are calling on UVic to re-conduct the investigation entirely — this time under a coaches’ code of conduct or SafeSport policy.

Lily Copeland, one of the three rowers to formally complain, has since filed a lawsuit against UVic and Williams — alleging that UVic delayed addressing her complaints throughout the autumn of 2018 and that both UVic and Williams failed to provide duty of care for their athletes.

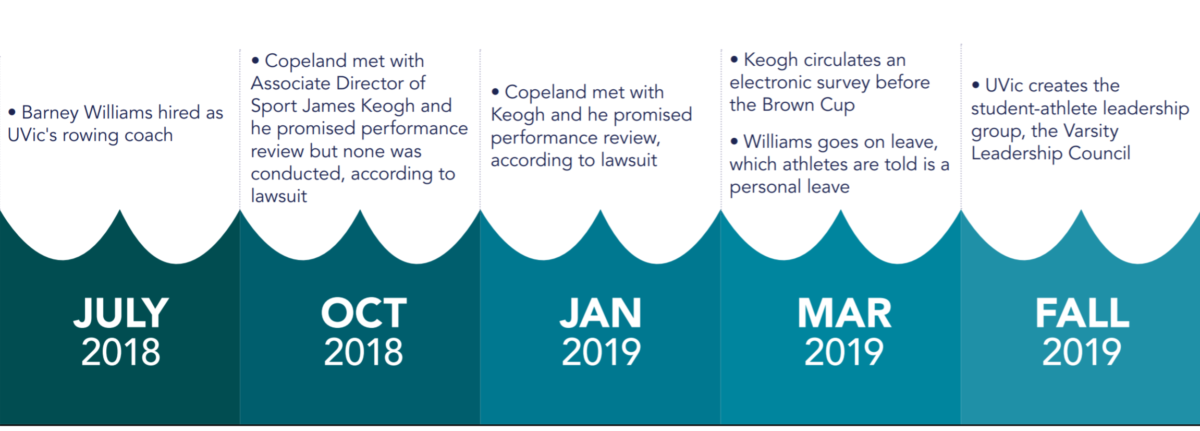

Copeland was a coxswain, the athlete who steers and leads the team at the front of a boat, for the 2018-19 season. Throughout the season, she spoke to then-Associate Director of Sport James Keogh regarding her concerns about Williams.

Copeland alleges she was publicly berated by Williams on multiple occasions and yelled at three to five times every week in a small, locked room. She says this made her late and sometimes absent for her classes and was detrimental to her mental health. The assistant coach, who brought her own concerns forward in December 2018, tried to support Copeland by escorting her to the parking lot and waiting for her outside the room.

In two meetings in October and December, Keogh promised Copeland that he would conduct a performance review soon. Copeland alleges no review was conducted.

Keogh was aware of these concerns for at least four months before finally deciding to circulate an online survey about the coach in March. At this point, Copeland filed a formal complaint with UVic’s Office of Equity and Human Rights (EQHR) and Rowing Canada (RCA).

Williams was hired in July 2018, with an eight-month probation. By the time Keogh took action and circulated the survey, the probation period had finished.

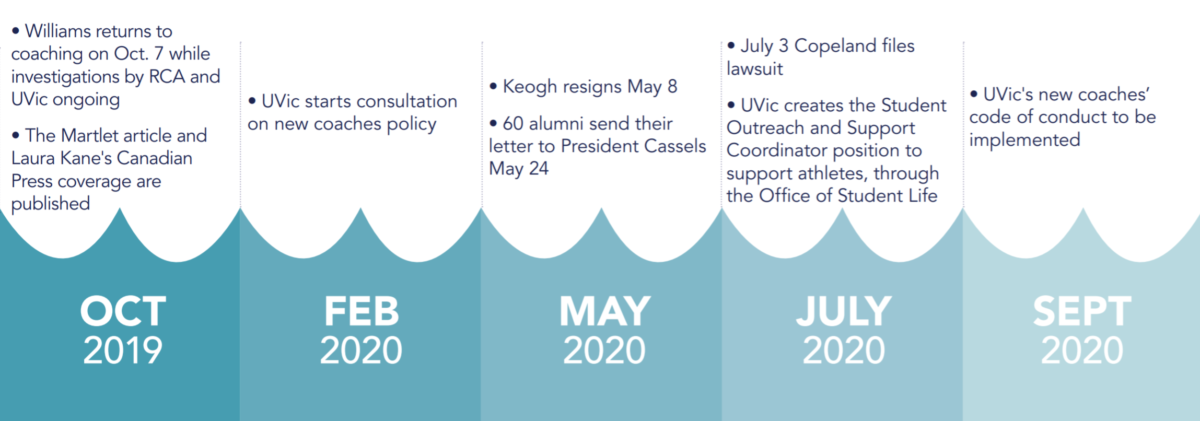

Keogh announced his resignation in May of this year.

Simpson reported that rowers suspected Keogh knew what was going on and deliberately delayed taking action. The survey was circulated before one of the biggest events of their season, the Brown Cup competition.

At this competition, which is referred to often in the lawsuit, Copeland’s boat won their race. Williams allegedly congratulated everyone except her. Shortly afterwards, athletes were told that Williams was taking a personal leave — they weren’t told he was under investigation by both UVic and RCA.

Copeland was one of three athletes to file a formal complaint. According to Copeland’s statement of claim, UVic’s lack of a coaches’ code of conduct made the investigation unreasonably narrow in scope.

But it wasn’t just Copeland. During the same season, four other rowers allege they had similar experiences, which they shared with Simpson at the Martlet last year. Another rower and an athlete’s parent came forward to the Canadian Press, followed by another three women in a follow-up article.

Leah*, one of the rowers who made allegations against Williams in Simpson’s initial article, quit the team in September of 2019. Leah alleged that Williams pitted girls against each other, used demeaning language about their mental health, and made them train without appropriate gear. When she left the team, Leah said Williams yelled at her in a public cafe.

In October 2019, Williams returned to coaching while the investigations by RCA and UVic continued. Since then, Williams says he has learned from various professional development programs.

“I am committed to ensuring that all current and future members of the roster have the support needed to achieve their goals on and off the water,” Williams said in an email statement to the Martlet. “This commitment includes constant reflection on feedback from current athletes and staff, working with experts to continuously improve my coaching skills and taking professional courses to work on my conflict resolution and communication skills.”

Cassbreea Dewis, EQHR’s executive director, maintains that EQHR’s processes are applicable to any student. EQHR has confidential and impartial processes, which can include a consultation, making an informal complaint, or making a formal complaint. Their office can investigate complaints and make recommendations for disciplinary action under the Discrimination and Harassment Policy or Sexualized Violence Policy. A formal complaint requires an independent investigator to analyze how EQHR’s policies apply to the case and provide recommendations for moving forward.

Dewis says the policy is applicable to everyone, and the investigators understand these different relationships even without a sport-specific element in the policy.

“EQHR works with external investigators to ensure they understand the specific context of the investigation including the power relationships,” Dewis said. She admits that the policy is not perfect, adding that it is mandated for review in early 2021.

The formal complaint option is the road less travelled. While 136 people consulted with EQHR from May 2018-September 2019 regarding the Discrimination and Harassment Policy, only 14 filed formal complaints. Five of those investigations found that the policy had been breached.

Copeland, her assistant coach, and two other rowers represent four of the 14 complainants. Whether or not the investigations found that the policy was breached is confidential.

Although attempts were made during the investigation to invoke either the Coaching Association of Canada (CAC) or RCA coaching codes of conduct, they were declined. The investigations sought to determine whether the allegations against Williams constituted harassment under EQHR’s policy. Whether or not he was a suitable coach was outside of the scope of the investigation.

By December 2019, UVic would have been aware of the allegations made through the formal complaint process, in Simpson’s article, and in Kane’s articles. From the time Williams returned from his leave in October 2019 to the time of writing, UVic has allowed Williams to continue coaching without the oversight of a policy designed to specifically investigate coaches for abuse.

UVic has opted to create their own policy, and began the consultation process in February 2020. Clint Hamilton, the university’s senior director of athletics and recreation, said the new coaches’ code of conduct will be unveiled this month.

SafeSport policies are mandated by the federal government for national and provincial sport organizations, such as RCA. Because universities are under provincial and not federal jurisdiction, they aren’t included in this mandate. Kane reported that seven of B.C.’s 14 public post-secondary institutions with varsity programs lacked a coaches’ code of conduct as of March — including UVic.

Other universities have taken different approaches to implementing policies on appropriate coaching conduct. Queen’s University modelled theirs after the CAC’s conduct policy. Camosun College’s policy includes a page that details a coach’s responsibilities and what is considered inappropriate.

At the time of writing, UVic declined to offer the Martlet details of their new coaches’ code of conduct or the new processes for student complaints they will be introducing. The new code is one of many initiatives that Hamilton says will support varsity athletics and the women’s rowing team at UVic.

“A lot of work has happened in the last 18 months and is continuing as part of a multi-faceted plan,” Hamilton said. “We want to ensure that student athletes can pursue high standards of individual and team goals in an environment that is free of bullying, harassment, discrimination or abuse of any kind.”

There will also be a new student athlete handbook. In the Office of Student Life, a new student outreach and support coordinator was hired in June to provide oversight, accountability, and support for varsity athletes.

In the autumn of 2019, a Varsity Leadership Council of student athletes was created to provide advice to UVic. Hamilton credits this group for coming forward with the student athlete handbook idea, among other initiatives.

The rowing team, Hamilton says, is doing well. They have been practicing at Elk Lake and CARSA while following COVID-19 guidelines.

“We have additional personnel working with the rowing teams — Marilyn and Howard Campbell, UVic alumni and internationally respected leaders in the rowing world, [are] to serve as key advisors,” Hamilton said. “We also monitored the team throughout the 2019-2020 season, working closely with the team’s student-athlete leader group. From all reports the team was doing very well.”

But according to a letter from alumni, these initiatives are far from good enough. The authors of the letter want UVic to re-conduct the investigations into Williams.

The letter, signed by 58 former Vikes rowers and two other varsity alumni, was sent to President Jamie Cassels in May. Since then, at least 10 more alumni have added their names.

Their other demands include that UVic conduct an independent investigation of the handling of this case, suspend Williams from his duties, hire a new coach, and begin a restorative reconciliation process for the athletes in the program and those that came forward with complaints.

Mike Reilly is part of this alumni group. He rowed for UVic from 1986 to 1990 and rowed for Victoria City Rowing Club as well.

“We felt that the way that UVic handled the situation took something that could have been handled in the early days and made it far worse,” Reilly said. “Since then [UVic] has robbed these young women of the opportunity to enjoy the sport in the way that we have.”

Jason Dorland was another one of the signatories. He rowed at UVic in the 1985-86 season and went on to row for the national team and in the Olympics. Both Dorland and Reilly had positive experiences while rowing for UVic and want to see that same culture replicated for the program’s athletes today.

“When I read about what went on, through allegations, if that was my child I would be concerned,” he said. “This is embarrassing. It’s embarrassing for the school, it’s embarrassing for the sport.”

Cassels responded to the alumni in a letter obtained by the Martlet. He repeated the new initiatives the university has implemented.

“The Vikes and the university in no way condone behaviour by coaches or any other employee that constitutes harassment, discrimination or abuse of students,” Cassels wrote.

“[Williams] wants you to know that, in consultation with experts, we have created a detailed professional development plan for him that includes coaching education workshops,” he added. “The coach understands the complaints that were brought forward, and he fully cooperated in the investigation.”

When asked how they felt about Cassels’s response, Reilly and Dorland were unimpressed.

Reilly said the promised new initiatives don’t address the allegations against Williams or do enough to support the athletes. Instead, the new initiatives seem to suggest that the university needs to make systemic changes to their sports programs, which Reilly says is not the case, as many athletes have positive experiences with UVic. To him, the issue surrounds one particular coach and UVic’s handling of the investigations.

Dorland added that this isn’t only about Williams and UVic, or even SafeSport — that a shift is needed in the old attitude in all high-performance sports that allows and enables abuse to continue if it wins races.

“This happens in locker rooms and on playing fields across the country every single day,” Dorland said. “We need to have a national dialogue around why we do sport. Because if the only reason we do sport is to win [sic], then that’s not a good enough reason … the reason needs to be for the healthy development of young people.”

“Is the point of UVic to produce high-caliber athletes or is it seen as an educational institution where students come to that university expecting a safe environment where they can grow and learn? … right now, I’m not so sure.”

As for the athletes who came forward, many of them have left the Vikes rowing program. In the letter, the alumni stress their belief that UVic has not done enough to support these women.

“UVic is essentially saying to these athletes ‘sorry, you’ll be a footnote in history as the last athletes to have their complaints dealt with under the old policy,'” the alumni letter reads.

Copeland declined to comment but gave the Martlet permission to use her story. Her lawyer could not be reached at the time of writing.

The university said that they could not respond to anything regarding the lawsuit as it is before the courts, adding that all of their comments in the article are not a specific response to the lawsuit. Williams also said that he had no comment on the allegations, “out of respect for the complainants and the confidentiality associated with an independent and impartial investigation and pending legal process.”

*Names have been changed to protect the identity of sources.