When Chihiro Asami felt a sore throat coming on, a possible COVID-19 diagnosis wasn’t her only worry. She was working at a local cafe when her manager suggested she talk to a doctor—something Asami is not comfortable doing in English.

An international student hailing from Miyazaki, Japan, Asami was busy taking her last set of courses at the University of Victoria (UVic). Like many others, health care access wasn’t at the forefront of Asami’s mind—until she was directly confronted with barriers to it.

Over the last four years of her degree, Asami has often chosen to attend non-essential medical appointments in Japan, where she is from. Beyond the cultural unfamiliarity with the Canadian medical system, language remains the biggest barrier.

“[Receiving health care in BC] is not as comfortable as going to [a] clinic in Japan because of the language barrier,” Asami admits. “I try…[to] minimize the health service that I receive here.”

She remembers feeling nervous about being sick, since the potential for transmission with customers and coworkers at the local cafe she works at was high.

The UVic Health Clinic has already switched to Telehealth services, so Asami had her appointment over the phone and then came in to be tested. To her relief, Asami tested positive for strep throat instead of COVID-19.

When she went to the pharmacy to pick up medication, the pharmacy hadn’t received the prescription order from the clinic.

“I was feeling really bad that day. So I really needed the medicine immediately,” said Asami. “I cried, actually. The pharmacist [said], ‘sorry, but there’s nothing [we] can do at the moment.’” Frustrated with the miscommunication, paired with the intense unwellness she felt, Asami left without her prescription.

She admits to feeling that if she had been more confident speaking English, she might have been able to get the medication she so badly needed that day.

Asami is not alone in feeling like there is a different system for BIPOC and racialized international students when it comes to receiving health care.

But access to the kind of health care BC is renowned for is not a universal experience. People of colour often have to contend with language barriers, cultural assumptions and underlying biases when accessing health care spaces. Going to the doctor is far from a simple task.

Over the last few months, racial tensions have seen an uptick, with increased reports of racism across the country, particularly in Vancouver and Toronto — significant hubs for Asian migration and settlement.

This has been devastating for communities of colour who have also seen higher infection rates than their white counterparts. While Vancouver does not currently collect race-based data, in Toronto, Black people and other people of colour make up 83 per cent of reported COVID-19 cases despite only making up half of the city’s population.

Racist jokes and language barriers

Long before the outbreak of the novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China, racial microaggressions were already commonplace.

For Georgia Yee, who serves as the AMS VP Academic and University Affairs at the University of British Columbia (UBC), decoding spaces of care is something that she has had to do from an early age whenever she took her Grandmother to the doctor.

“[My grandmother] wouldn’t be able to get past [the] language barrier or communicate, and the health care practitioner would get really, really mad,” said Yee.

Combined with the cultural barriers between her grandmother and her health care workers, Yee remembers associating her grandmother’s inability to speak English with a sense of frustration.

“‘Why can’t my grandma just learn English?’

“As a child, that’s something that I remembered thinking,” said Yee. “And now that I look back on that, [I think] it’s really the lack of training that health care practitioners receive.”

After nationwide reports of xenophobic attacks against racialized persons came to light, Statistics Canada launched a survey focusing on the impact of COVID-19 in individuals’ experiences of discrimination throughout the country.

Yee’s family in Alberta experienced this kind of discrimination first hand at the onset of the pandemic.

“I’ve definitely seen a lot of anti-Asian sentiment really amplified in light of COVID … [My family] had their property vandalised. There’s no indication that [this] was specific[ally] anti-Asian, but a Chinese-style lantern [was] knocked over.”

However, Yee sees overt racism to be far more permissible in Vancouver than in her hometown, Calgary.

“[In Vancouver] it is far more acceptable to make bat soup or wet market jokes, [but] they all contribute to a pyramid of [violence].”

In the 2019 AMS Academic Experience Survey at UBC, more than a third of students reported experiencing race-based discrimination. For Chinese students, this figure rose to 50 per cent, for Chinese international students rates were at 63 per cent.

These experiences of racism can wear on a person’s mental health.Despite this, Yee also believes that there are certain stigmas attached to seeking counselling services as an Asian person.

“I’ve often felt that my perspective has not been taken into consideration when seeking mental health support. [There are] different racialized stereotypes of a ‘socially-pressured Asian’ [who] is under pressure from [their] parents,” said Yee.

Asami and Yee are two examples of a greater pattern in British Columbia.

Access in layers: the student health care experience in BC

Rebecca Shang requires regular acupuncture treatments after a car accident three years ago. According to Shang, ICBC requires a referral for her acupuncture claims.

This means frequent doctor’s visits at Victoria’s Jubilee Medical Clinic to obtain referrals.

While the majority of her appointments at the clinic have gone smoothly, Shang’s experience with one particular physician brought cultural barriers in the BC health care system to light.

The physician refused to provide a referral to acupuncture services based on his lack of confidence in it as an effective form of treatment. She recalls him allegedly telling her that acupuncture seemed fake because it failed to yield immediate, short-term benefits for her.

Although medical practitioners have differing opinions on treatments for their patients, acupuncture is a well-known method for pain management. A 2018 study done by the American Academy of Family Physicians found that it helped some patients with chronic pain management beyond a mere placebo effect — an assumption which has often been attributed to non-traditional, non-Western forms of treatment.

For Shang, the treatment has been effective over a longer period of time. She ultimately had to switch to another doctor at the same clinic to continue her acupuncture treatments.

Student health services respond to COVID-19

In the face of unique challenges resulting from COVID-19, Student Health Services at both UVic and UBC have moved to Telehealth models. But currently, only students within Canada are eligible for appointments.

This September, a new service for UVic students called SupportConnect, which will provide around-the-clock mental health services to students, is set to launch in 27 languages.

At UBC, the Empower Me platform fulfills the same role, with the program offering support by phone in multiple languages. However, services are generally limited and only operate in a short-term capacity.

UBC Counselling Services has also begun the work to create spaces for BIPOC students. Jenni Clark, associate director of Counselling Services, recognizes the distinct needs of students of colour. She said the office is trying to address this through a BIPOC-specific support group.

“[This] would be safe place for [students] to come and be facilitated by staff [who] themselves identify as BIPOC,” said Clark.

As health care institutions on the UBC campus adjusted to protocols imposed by the provincial government, service usage declined.

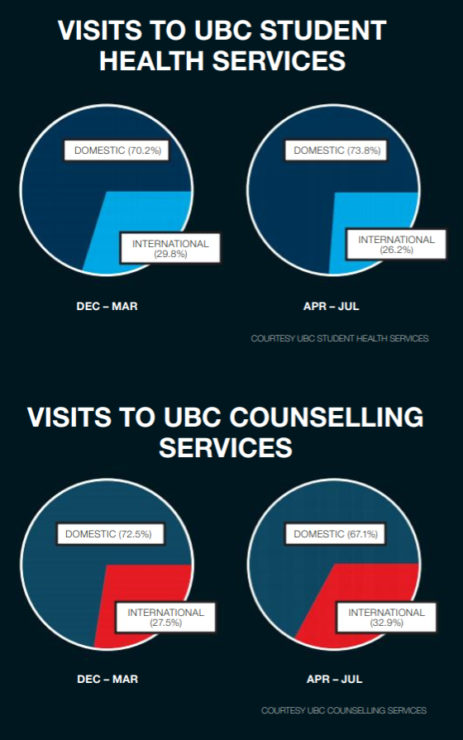

According to UBC Student Health, there has been a 21.59 per cent net decrease in student health visits from the pre-COVID-19 period (December to March) to the first few months of the pandemic (April to July). There was a decline in the proportion of international students accessing these services.

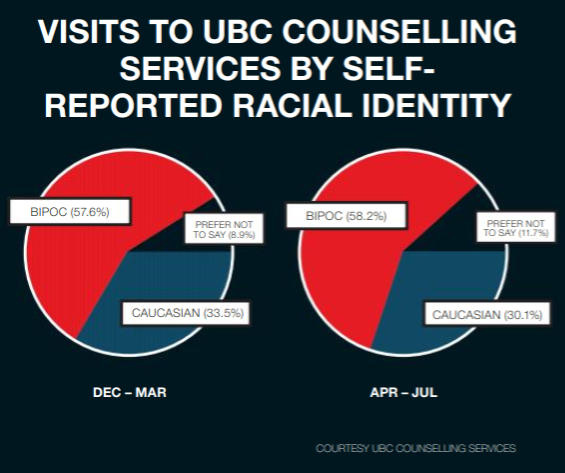

Mental health services at the institution also saw a net number of visits decrease with 50.48 per cent fewer visits from during the first quarter of the pandemic (April – July). Despite this, the proportion of international students who sought access increased by 5.4 percent. The amount of students accessing the services who identified as BIPOC also increased by 3.4 per cent.

At UVic, health appointments from the same time frame declined 57.61% while mental health services saw a decline of 34.45%. However, the COVID-19 period also coincided with the integration of Health and Counselling Services into the Student Wellness Centre, which impacted student access figures in the April to July time frame.

Stephanie Inman, communications coordinator at the Student Wellness Center at UVic, said that numerical data on accessing health services focusing on international versus domestic student access is generally not collected. This is also the case for race-based data pertaining to Health and Counselling services.

Health care providers at UVic, UBC undergoing anti-racism training

In the wake of the death of George Floyd this past June, universities across BC have also been making commitments to engaging in anti-racist work. At UVic, President Jamie Cassels committed to “continuing the necessary work to confront racism, recognizing that many current assumptions, attitudes and habits stand in the way of change.” At UBC, President Santa Ono committed to “dismantlling the tools of oppression and white supremacy that remain prevalent and entrenched in our everyday systems.”

Health services at both institutions have attempted to bridge gaps in coverage through training.

UVic’s Student Wellness Centre, for instance, implemented “ongoing professional development around anti-racism, accessibility and equality,” in addition to Indigenous Cultural Acumen Training for its staff. Inman placed particular emphasis on making health spaces at UVic accessible for Indigenous students, with the option to work with Indigenous-identifying counsellors.

The Centre said it works in collaboration with International Student Services to coordinate health care access and arrange for translation services or other accommodations on an emergent-need basis.

Marna Nelson, director of Student Health Services is hoping that her staff remains informed about racial disparities in health care through professional development sessions. Annually practitioners participate in continuing medical education which includes formal courses on diversity as well as the San’yas Indigenous Cultural Safety Training course. They also have a Student Diversity Initiative as well as a small group training on trauma informed care.

“These sessions deal with [the] topics and training so that individuals in our health unit[s]…are learning strategies to help with these very important issues,” said Nelson.

UVic has also been moving toward providing a stronger support system for BIPOC students. The Wellness Centre has been using student feedback to tailor its counselling support group this upcoming fall, a Student Advisory Group for the Centre is in the works to better tailor services toward the needs of its service population, and a Diversity and Inclusion Working Group is also being implemented at the Centre to address specific issues uniquely relevant to students of colour.

Race and health care beyond COVID-19

In mid-June, Provincial Health Minister Adrian Dix announced an independent investigation on Indigenous-specific racism in the BC health care system, appointing UBC law professor Dr. Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond to spearhead the project.

The investigation will be the first comprehensive look into the direct impacts of racism, in explicit or implicit forms, in health care delivery throughout the province.

Turpel-Lafond’s team is looking at a range of racialized experiences and systemic issues in the way health care is delivered and experienced by British Columbians—particularly those from racialized backgrounds.

While the scope of her report is currently on anti-Indigenous bias, she believes there is a need to systematically examine intolerance and racism against other marginalized groups in BC.

“All forms of racism should be examined with the kind of skill set that understands that all racism isn’t the same,” said Turpel-Lafond. “We understand that it’s all wrong. It’s discrimination. It’s illegal. It’s inappropriate, but how racism affects people and affects those implicit and explicit values and beliefs needs to be unpackaged. And how much work we’ve not done [on] that is staggering.”

In June 2020, Vancouver City Council announced its unanimous endorsement of “a call for race-based and socio-demographic data in BC.”

The council’s motion proposed that the absence of such data ignores the disproportionate rate of health complications among marginalized groups within the larger population,“resulting in missed opportunities to address long-standing health inequalities.”

This approach is reflected in UBC’s and UVic’s health care systems, both of which do not mandatorily collect detailed, race-specific data.

Turpel-Lafond points to the need for reform in the health care education system itself. Students in health care, she said, do not currently have adequate outlets to speak out about incidents of sexism, racism, homophobia, workplace bullying and beyond.

Combined with a fear of workplacediscrimination, health care students also serve as examples of marginalization by existing institutions. She stressed the need for students to continue pushing for their voices to be heard.

“[This initiative] allows me to go into the medical schools, nursing schools and elsewhere and say, ‘your own students have been addressing this. What have you [as institutions] been doing?’ But the fact that they [the students] have been shut down—I don’t want them to get discouraged. They need to double their efforts.”

The data collection phase of the project is set to conclude by the end of this year.

Many Canadian universities, including UBC and UVic, do not collect race-based data on the makeup of their student populations. As a result, detailed data on how race impacts health care delivery is not currently available.

For students like Yee, racism and accessible health care are interconnected issues.

“Without acknowledging that racism is already intrinsically part of this crisis [of COVID-19] we can’t move forward,” she said.

Danni Olusanya and Dorothy Poon wrote this piece as a collaboration between the Martlet and The Ubyssey to better understand the racialized experiences of post-secondary students accessing health care on the West Coast. Editing was also done collaboratively, while The Ubyssey’s Lua Presidio designed the graphics for this piece.