From the UVSS to the BoG and every level in between, students say BIPOC representation is needed

If you’re a student at UVic, chances are high that most of your professors, your dean, and your president are white. Black, Indigenous, and people of colour (BIPOC) students, staff, and faculty know the feeling of walking into an all-white class or meeting all too well. The Martlet spoke to three BIPOC students with experience in clubs, course unions, the UVSS, the Board of Governors (BoG), and the Senate. According to these students, lack of representation at UVic is causing BIPOC students to take on more work in advocacy roles, feel uncomfortable in many spaces, and burn themselves out.

Now, as the Black Lives Matter movement continues to gain momentum, post-secondary institutions are reckoning with systemic racism. At Ryerson, students asked the university to change its name. The university’s namesake, Egerton Ryerson, was instrumental in the development of Canada’s residential schools. Likewise, Simon Fraser University has committed to changing the racist name of its sports teams, formerly known as “The Clan.”

Here, at UVic, nearly 300 faculty members, staff, and students have penned a letter to President Jamie Cassels requesting that the university take more concrete anti-racist actions. Cassels replied by citing some of the initiatives UVic is proud of, including anti-racism training, preferential and equitable hiring policies, and the upcoming 5 Days of Action and virtual anti-racism symposium to be put on by the Equity and Human Rights office (EQHR).

However, it can be hard to delve into these issues without the data to explain them. Although the Martlet was able to obtain data on the number of Indigenous students at UVic as well as employment equity survey data on faculty and librarians, we were not able to obtain data on BIPOC representation among students, deans, department chairs, the BoG, the Senate, or the UVSS board.

The data (and lack thereof) on diversity at UVic

UVic has made concrete attempts to increase diversity and these steps were recently rewarded when the university was named one of Canada’s Best Diversity Employers. EQHR provides anti-discrimination training, and the university’s hiring policies aim to promote equity, including by engaging in preferential hiring.

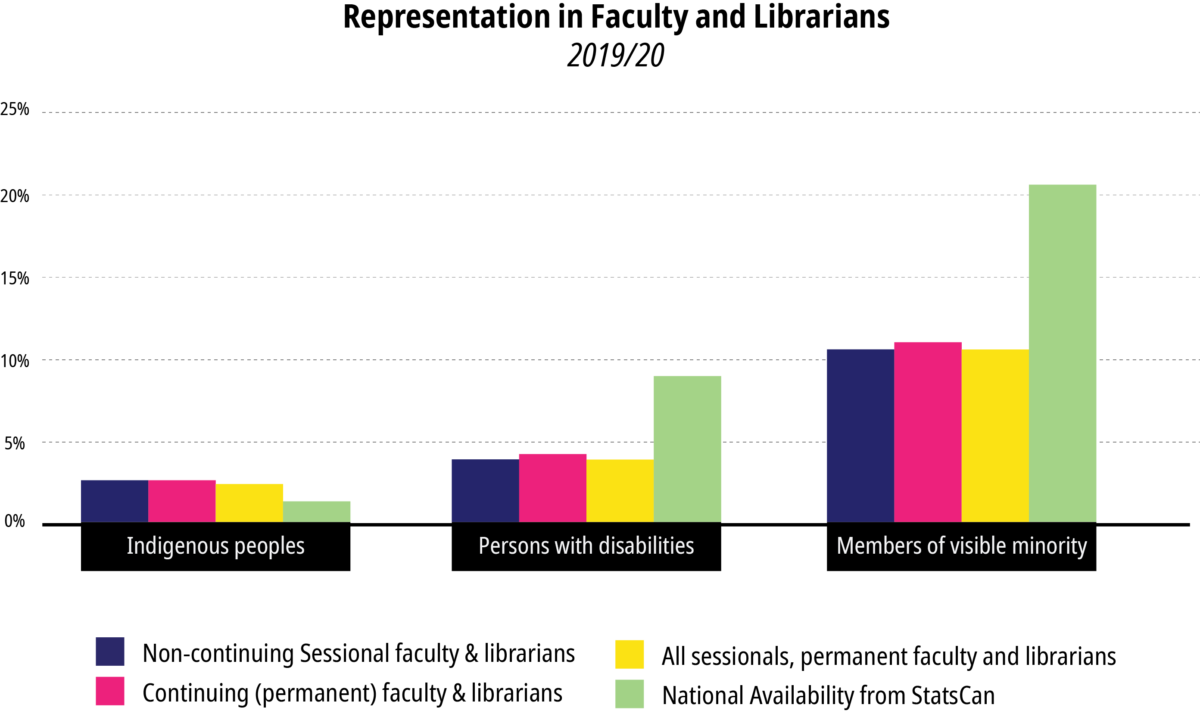

UVic asks all faculty and librarians to self-identify in an employment equity survey. In 2019, around 90 per cent of those eligible completed it.

UVic uses this data to see how many Indigenous people, persons with disabilities, and members of visible minorities work at the university. They can also split this data into non-continuing sessional faculty and librarians, continuing sessional faculty and librarians, and permanent faculty and librarians. If there are five respondents or fewer, the university doesn’t report the data for privacy reasons. In 2019, there were no Indigenous people, persons with disabilities, or members of visible minorities reported in the continuing sessional category.

Skye Lacroix advocated for the Department of Political Science to hire an Indigenous professor for over a year. Lacroix is of Inuit and Gwitch’in descent, and a recent UVic grad.

Although her efforts were ultimately successful and the department is currently hiring for an Indigenous professor, Lacroix says she faced opposition from some professors in the department who were opposed to exclusively hiring an Indigenous candidate. This advocacy work was a lot for Lacroix to take on in addition to her courses, and her grades suffered as a result.

“So much of my time and energy went into trying to lobby for more Indigenous representation in my department that I was falling behind in my classes,” Lacroix said. “I had to act as a supporting role for a lot of people. That shouldn’t have been me, the university should have hired someone.”

But she felt like it was important, given her own experiences on campus and the support system she discovered through Indigenous faculty members.

“My biggest support was from professors that were Indigenous,” Lacroix said. “That’s the biggest thing: hiring more Indigenous people as authorities on campus, like as [professors] and not just as sessionals but full-time tenured profs.”

The chair of the department, Dr. Scott Watson, told the Martlet that the department fully agrees that diversity among faculty members is important. However, Watson added that in the discussions for the creation of this position, all factors had to be considered.

“In the course of discussing a limited or preferential hire, members of our unit consider the full implications of doing so, both positive and negative,” Watson said. “Articulating and discussing the potential negative implications of a limited or preferential hire does not mean opposition to hiring designated candidates.”

UVic has a dedicated fund for faculties to hire Indigenous professors. In 2020, they created seven new positions. Additionally, the university recently hired Ry Moran as the associate university librarian for reconciliation. UVic also has an Elders-in-Residence program that operates five days a week. During COVID-19, the Elders are using iPads to stay connected with students.

Statistics Canada collects information on the composition of the workforce available across Canada to fill certain roles. In spring 2020, Statistics Canada reported an increase in the availability of persons with disabilities available to fill faculty and librarian roles from 3.8 per cent to 8.9 per cent. Before this, the proportion of UVic staff in these roles who identified as persons with disabilities was comparable to the availability in the population, though representation at UVic now lags behind. When comparing UVic’s level of representation to the population available to fill faculty and librarian roles, UVic has over the national availability for Indigenous faculty but members of visible minorities are underrepresented by 10 percentage points.

Permanent faculty have greater job security, and get paid significantly more than non-continuing sessional faculty. For a 1.5 credit course, sessional lecturers make between $1 455 and $1 768 per month. Associate and assistant professors typically make around $100 000 a year, on average.

But there are still discrepancies in how much BIPOC representation there is on campus, and gaps in the data collected on race. The Martlet was not able to obtain data on how many faculty or librarians intersect multiple identity categories. The university did not have data, for instance, on the number of Indigenous women on campus.

The Martlet was also not able to obtain data on the race or gender of faculty deans. Deans are responsible for developing the budget and staffing plans, leading academic planning, and applying university policy. They also oversee the appointment, recognition, and salary advancements of staff.

UVic does not ask students to self-identify their race, and does not collect data on how many Black students or students of colour there are on campus.

“Personal student information such as race is not collected because it is not used for university admission,” Paul Marck, the associate manager of media relations and public affairs, explained.

Indigenous student numbers up in some faculties more than others

Marck said the university follows a “provincial standard in collecting self-identifying information about Indigenous students.”

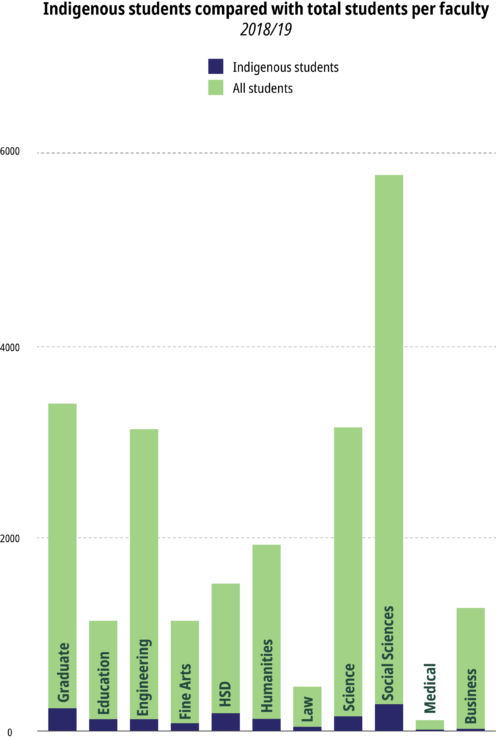

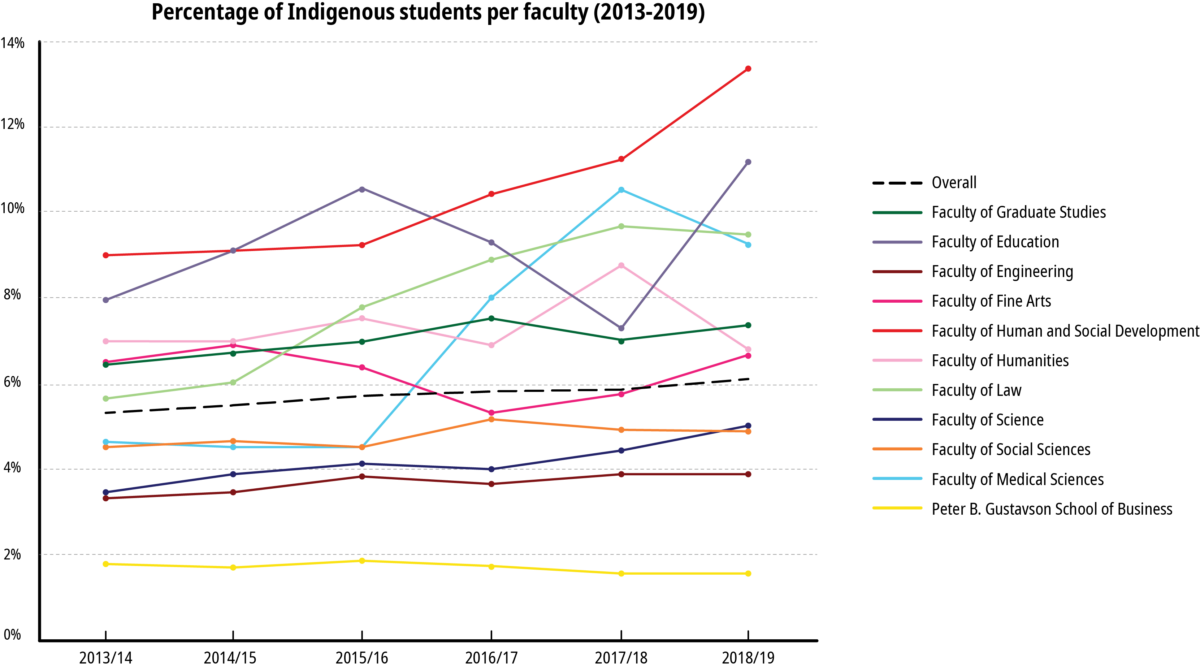

In recent years, Indigenous enrollment has increased across most faculties. In the Faculty of Law, it’s almost doubled from 5.67 per cent in 2013 to 9.49 per cent in 2018. Of UVic’s 11 faculties, two (business and humanities) reported a lower percentage of Indigenous students in 2018 compared to 2013.

The Peter B. Gustavson School of Business had just 20 Indigenous students of 1 268 total students in 2018 — 1.5 per cent. In two of UVic’s largest faculties, the Faculty of Social Sciences and the Faculty of Science, roughly five per cent of students were Indigenous in that same year. The Faculty of Human and Social Development had 13.38 per cent, the highest percentage of any faculty.

In 2018, six per cent of UVic students were Indigenous. The number of Indigenous students has increased by 52 per cent since 2009, but the percentage of Indigenous students as a proportion of all students is pretty much a flat line. The university hopes to double Indigenous enrollment in the next 10 years so that Indigenous students comprise 10 per cent of the overall student population.

Lacroix said she has been in consultation with UVic about their plans for increasing Indigenous enrollment. Although UVic is focusing on encouraging more Indigenous students to attend, Lacroix says Indigenous students may drop out if they don’t feel well represented once they get on campus.

“I thought the whole process was backwards … [UVic is] just very colonial,” Lacroix said. “They should start with engaging more with their Indigenous students and including more Indigenous perspectives into curriculum and classes and syllabi.”

Although having more BIPOC students, staff, and decision-makers would help, Lacroix says there are limitations on the effect that representation alone can have.

“The university is a colonial institution in and of itself, so in order to decolonize they would have to radically transform their entire institution in order to centre BIPOC and Indigenous folks, and actually listen to them instead of pushing back so much,” Lacroix said. “It’s not a welcoming space for us.”

Lacroix credits the support of white allies for speaking up when BIPOC people aren’t listened to or dismissed. In her degree, she says her individual professors were supportive and accommodating when she was actively organizing Wet’suwet’en solidarity actions.

Anti-racism training from EQHR hopes to make campus a more respectful space

One of the people working on anti-racism work at UVic is Moussa Magassa, a Specialist in Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, and Partnerships at EQHR. He works to educate people on the university’s anti-racism work and, ultimately, make the campus a more respectful place. EQHR works with all of the different offices and programs at UVic, from the UVSS to new student orientation.

In developing a three-stage anti-racism training program, EQHR had a PhD student research all of the anti-racism education programs at post-secondary institutions in Canada before a committee designed and developed UVic’s program. The training is accessible for anyone at the university. It includes education on systemic racism and socialization and asks the workshop attendees to question their own biases and take action on both an individual and systemic level.

He recognizes that there is racism at the university and in broader society, but he encourages students to be part of changing that. He has received “a flood of email and requests” for his anti-racism workshops since Cassels drew attention to it in a statement in June.

“All the different departments are trying to also encrypt an anti-racism lens in their work because right now … the conversation is out there and people are really willing to change,” Magassa said. “We have to capitalize on that and give them a product that’s worth their expectations and to really address racism on campus.”

BIPOC representation at decision-making tables

UVic is governed by two decision-making bodies: the BoG and the Senate. We were unable to obtain race-based data for either of them. Most of the people on the BoG are appointed by the Lieutenant Governor for three-year terms. These appointees are supposed to “reflect the diversity of our province.”

Isabella Lee is a woman of colour with four years of experience in student governance. She has been the Third Space representative and Director of Students Affairs with the UVSS, and a student senator. Lee just finished her term on the BoG.

With the BoG, there’s only one undergraduate student spot and students are responsible for their own campaign. Lee said that’s “especially scary for people of colour.” When she was on the BoG, she found it difficult to advocate for issues that mattered to her.

“The university ultimately doesn’t really want to shake the system,” Lee said. “If we put out a controversial statement or if we divest too fast or stop campus policing … [people will ask]: what if it affects registration?”

“People aren’t willing to take that extra step and when you’re the only person on the BoG that wants to … it’s still not enough to make that change happen,” Lee added.

Lee said an easier entry point for BIPOC students may be the UVSS because you can run with a group and support one another. In March every year, the UVSS elections take place and students can run in cooperative groups of two candidates or more. Students can also run as independents.

The UVSS does not collect self-identification-based data on race. Last year, the Hear slate remarked that it was a rare time when Indigenous people were overrepresented in a colonial institution. Their slate swept the election, and the UVSS board had four Indigenous students and an NSU representative.

Currently, there are no Indigenous people on the UVSS board. Tubeishat says she has noticed the lack of Indigenous representation on the current board. Soon, when the Firekeeper from the NSU joins, they will be the only Indigenous person on the board. Lacroix says she knows what it’s like to be the only Indigenous person on a board, and felt like she had to represent the entire Indigenous student body herself.

Dalal Tubeishat was on last year’s UVSS board as a director-at-large. She is the current Director of Student Affairs, and has noticed the lack of Indigenous representation on this year’s board. The conversations around the table at meetings often ask how the university feels about a certain move, instead of “centring the conversation on the historical context of the colonial background,” and how BIPOC folks feel on campus.

“It’s really really difficult to be one of the only voices saying that, to be always advocating on behalf of minorities,” Tubeishat said. “I’m dealing with white people all the time … I really don’t have any co-workers who are people of colour [besides some of the directors-at-large].”

At the UVSS, a lot of the management and support staff are white. Although both Lee and Tubeishat said the staff are excellent, they agreed that it can be really hard for people of colour to only receive advice from people who may not see things from the same perspective.

“Every student is qualified to run … but it’s a tough sell.”

In the last UVSS election, Tubeishat was the first independent candidate elected in over three years. She said running as an independent made her accountable for her platform, which focused on ensuring BIPOC voices are heard.

While campaigning, Lee was cautious about how much she centred herself as a woman of colour. When she ran for the municipal election in Oak Bay, a mentor told her to avoid drawing attention to her race or her gender as much as possible. She found herself doing a balancing act — bringing up issues that mattered to women and people of colour, but not too much because it made students uncomfortable.

“I think it’s really hard, even for me, someone who has been in student politics for the last four years, to [encourage BIPOC students to run],” Lee said. The reality is that [running for office] takes a whole emotional toll on you.”

Although she admits she maybe could have mentioned issues related to race more, the general sentiment she got from students was that they wanted to hear about things like affordability and climate action.

“If you make [race] your core issue you alienate a lot of students,” said Lee. “I think at UVic we’d like to pretend we’re progressive and great … but a majority of students honestly don’t really care about the UVSS or the BoG.”

In the last UVSS election, only 14.8 per cent of students voted.

Lee spoke of her own work in trying to get sexual assault support for clubs. She thought she would be able to create change when she got into a lead director position. Instead, she quickly realized how little she could do at the UVSS level.

“You get representation on the board and you hope change happens, but then you still have to work within this framework that isn’t working for people of colour,” Lee said. “It’s a lot just to get to that table, but then when you get to that table still having to work in the system … doesn’t really help.”

Although both Tubeishat and Lee encourage other BIPOC students to run, they both described the UVSS as a “toxic” environment.

“The UVSS has been a space occupied by white people for a really long time. And the only way that we can change that is by encouraging our BIPOC peers to run,” Tubeishat said “[But when people ask me about running for the UVSS] I’m going to be brutally honest about the systemic racism that is so prevalent here, and how internally entrenched colonialism is into everything we’re doing.”

Lee encourages students to run because “every single student is qualified.”

“[But you are] signing yourself up for a year of a lot of toxic environments, and maybe change will happen. And that’s a really hard sell.”

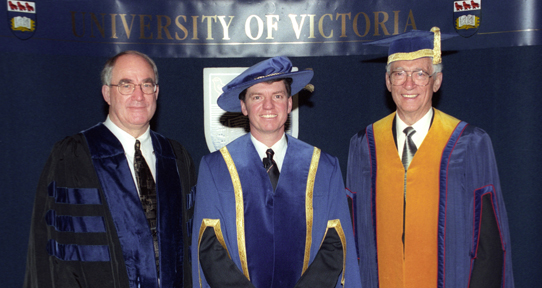

All the presidents are white men

The president is UVic’s highest-ranking and highest paid decision-maker. The current president, Jamie Cassels, was slated to resign June 30 but stayed on due to the pandemic. The selection committee for his successor had to pause due to COVID-19, but they’ve recently resumed meeting. Looking at the list of past presidents, it’s clear many, if not all, were white men.

However, Lee said that even if UVic had a BIPOC president, it might not make a substantial difference.

“The president is so high-level that most things that come to his table have already been decided on,” Lee said. “If you don’t have people all the way up the chain it’s really hard.”

“The people around the president and the president himself are white, and so when you want to bring something up … you have to take into account the staff and the faculty that are also in this and the reality is they’re white too.”

The presidential appointment procedures indicate that the candidate pool should be widened as much as possible, in order to “contribute to the further diversification of the University.”

Tubeishat still says that she hopes the university will break the trend and select a BIPOC president to replace Cassels.

“As far as picking a president for after Cassels, there really should be preference towards women, preference towards people of colour,” Tubeishat said.

“There’s never a shortage of qualified people, there’s just a shortage of people who will pick women and people of colour.”

Years provided for data indicate the fall term (e.g., 2018-2019 is written in this article as 2018).