This story discusses police killing Black people and police brutality. These elements may be difficult or traumatic for some folks to read.

At the time of print, it has been four months and 22 days since March 13 — the night that 26-year-old Louisville, KY EMT Breonna Taylor was shot to death by police officers, while sleeping in her own apartment.

Two months and 29 days later, on June 11, the Louisville Metro Council passed “Breonna’s Law,” banning “no-knock” search warrants such as the one police used to enter Taylor’s home. 12 days later, on June 23, officer Brett Hankison was terminated by the Louisville Metro Police Department.

Since that time, #BlackLivesMatter protests have taken the United States, Canada, and over 60 other countries around the world by storm, according to a July 2020 article from Vice. In response to the brutality and shootings of hundreds of Black people by police over several decades in United States history, the protesters called for the defunding — in some cases, abolition — of municipal police forces across the country. Cities such as Baltimore, MD, Minneapolis, MN, and Los Angeles, CA have attempted to meet the nationwide call for change.

However, as hard as the Black Lives Matter movement pushes for systems to be dismantled, many calls remain unanswered with minimal signs of positive change on the horizon. Officers Jonathan Mattingly and Myles Cosgrove remain employed with the Louisville Metro Police Department, and none of the three men involved have been arrested, charged with murdering Taylor, or imprisoned, as the movement has relentlessly demanded for months.

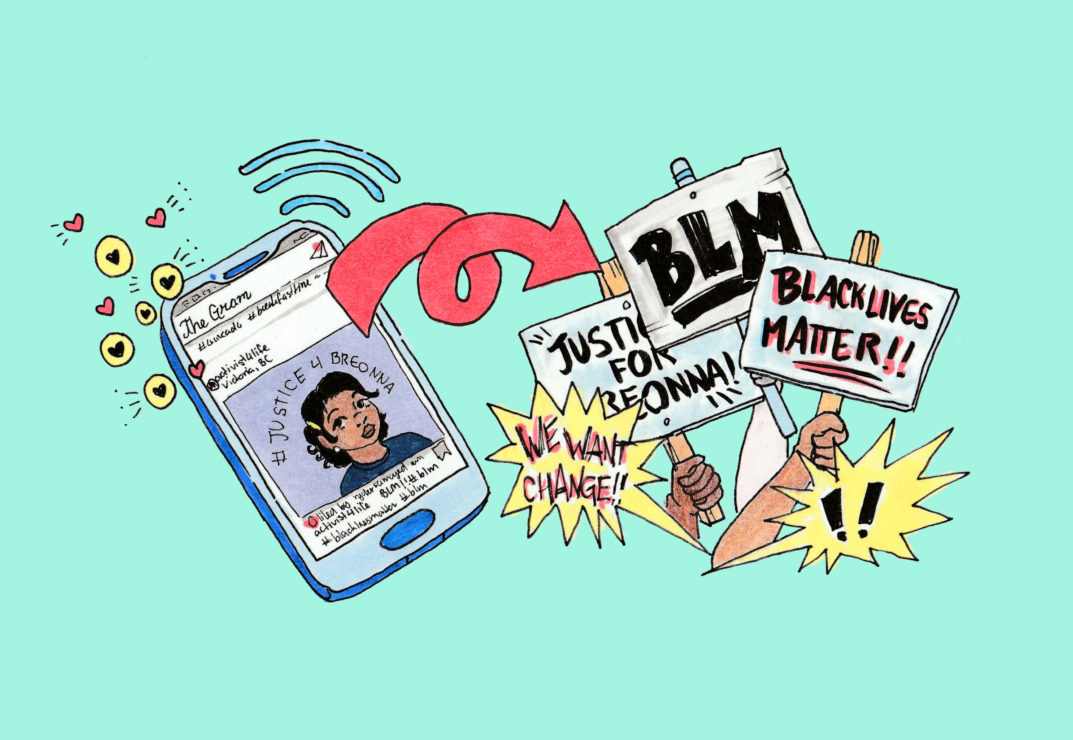

Social media platforms are inundated with messages to “arrest the killers of Breonna Taylor,” taking the form of tweets using the call as a punchline, music videos, and parodies of earlier internet fads. This has reached the point of what some digital media scholars are calling “memeification.” Critics of this form of attention argue that “dressing up” the issue is not in fact helpful for raising awareness, but actively harmful as it centres the messenger and downplays the seriousness of Taylor’s killing.

I am inclined to agree — and being a Canadian, I am part of a country that often fails to recognize its own problems and instead flaunts the apologetic and nice attitude we’re universally known for. Despite the fact that the shooting occurred on the opposite side of a foreign country, these meme-ified cries for justice for Taylor continue to dominate my feeds. While I certainly agree that the international attention for Taylor is justified, I can’t help but question its effectiveness, particularly given how few posts offer links to organizations that will actually further this cause.

What causes me further concern is that while I see so many of these messages, I see almost none highlighting Black Canadians who died in equally problematic circumstances; Ontarians Regis Korchinski-Paquet of Toronto, and D’Andre Campbell of Brampton being recent examples. The officer who shot Campbell has refused and is not legally required to submit his case notes to or give an interview with the Special Investigations Unit (SIU), despite being recommended to do so. The death of Korchinski-Paquet remains under investigation by the SIU.

For Canadians to bombard each other with objectively useless but trendy messages about a case over which they have little influence, while ignoring problems over which they at least have some, is a hallmark of this country’s tendency to get unhealthily involved in the United States’ problems while marginalizing our own and enforcing a superiority complex on no real moral ground.

If we really want to make Canada a better place, we must get off social media and make tangible and sustainable steps toward improving our communities. We must focus our energy not only on the occupants of 42 Sussex Drive, but on our city councillors, our union leaders, our MLAs, school boards, and all other levels of governance over which we can actually have influence if we come together and show up.

It is on those levels that we can begin to genuinely address the glaring issues in Canadian society that bring us so much depression and anxiety — such as the fact that more than 100 Indigenous-run communities across the country are under long- and short-term drinking water advisories. Or Premier of Alberta Jason Kenney expressing that he is “very concerned” about a rise in COVID-19 cases despite allowing 750 000 Alberta K-12 students to return to classrooms in September. Or, of course, the killings of Korchinski-Paquet and Campbell, and many BIPOC in Canada before and after them by municipal police and RCMP forces.

It is vital, not just for Canadian activists but worldwide, to remember the importance of committing to a realistic lane and keeping our feet on the gas on our own highways. The more city council meetings we attend, the greater our chances become of attaining victories like Breonna’s Law.