How one former cartoonist confounded people in both the Martlet and the New York Times

For student journalists who have written for the paper over its 70-year existence, the Martlet is often dreamed of as a first step towards working for a prestigious institution like the New York Times. How often does that really happen, though?

For Martin Ashwood-Smith, who volunteered with the Martlet in the late 70s and early 80s, this was an especially unlikely event. He didn’t even write articles during his time here — he was a volunteer cartoonist.

But now, pick up a copy of the New York Times on any given Friday and there’s a good chance you’ll see his name. It’s spelled the same way it was back in those Martlet issues from the 80s, and it’s right next to the same thing — a devilishly difficult crossword puzzle.

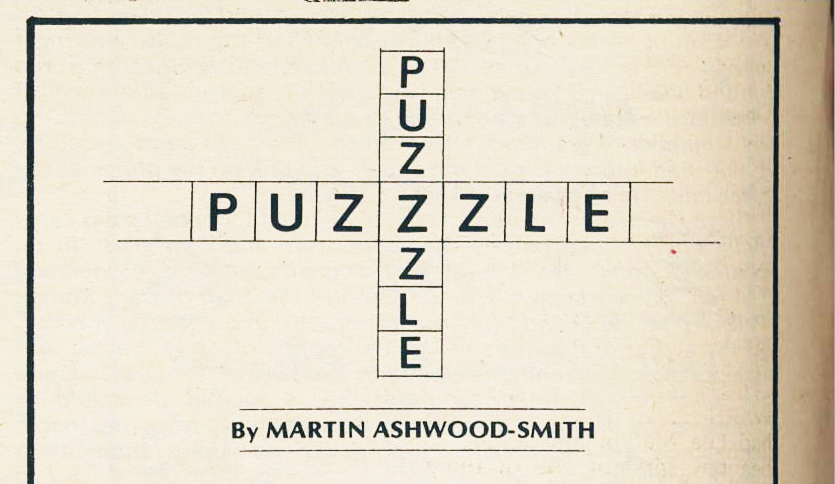

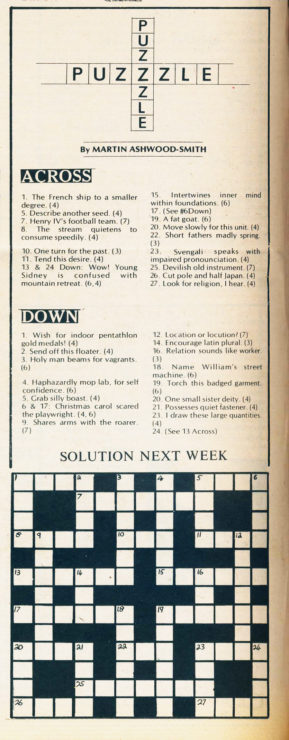

The London-born, Victoria-raised author and cruciverbalist has written crosswords for USA Today, the Washington Post, and, of course, the New York Times. Ashwood-Smith estimates that over 1 000 of his crosswords have been published since he started in the 1990s, ranging in difficulty from the head-scratching to the near-impossible. (For an example of the latter, check our back page.)

Getting started

It’s been a full-time job for Ashwood-Smith for many years, and it all started as so many great ideas do — with a Felicita’s-fuelled folly.

“I contributed to the Martlet — cartoons, I think, from about 1976 onwards,” Ashwood-Smith said, speaking to the Martlet in James Bay, where he currently resides. “Then I started to do some comic strips, and then I got interested in crosswords. I started to construct them with a friend of mine . . . I knew the editor, they wanted to run something anyway, and it was popular.”

Ashwood-Smith recounted the same story to the New York Times when they profiled him for their “Who Made My Puzzle?” series — a profile of regular crossword contributors for the paper — where he described the process in detail, starting at the campus bar.

“Several beers later, something resembling a 13×13 cryptic crossword emerged. It was published in the student newspaper. The editor wanted more, and bribed us with a small cheque. As far as we were concerned it was free beer money, and unsurprisingly we managed to make it a weekly feature,” Ashwood-Smith told Deb Amlen, the New York Times’ head writer and editor of their Wordplay section.

“It certainly gave me a good excuse to spend an inordinate amount of time in the student pub. So I don’t think crosswords did my grades much good.”

An unlikely helper

But the crosswords were enjoyed, and by one UVic student in particular: future Member of the Legislative Assembly and B.C. Green Party leader Andrew Weaver.

“He kept on winning,” Ashwood-Smith recalled. “And so he came in, and after the third time . . . [he said], ‘you’re using too many anagrams.’ So he sat down and we were just having a chat — he was really friendly — and we got along really well.”

So well, in fact, that Weaver began to help with the construction of the crossword.

“At least three of them, maybe four, he co-wrote, in a sense,” Ashwood-Smith said.

Submitting to the New York Times

Ashwood-Smith finished with the Martlet after graduating, but the crossword bug had bit him. (“If you have a cure, please let me know,” he said in his NYT interview.) His next step was to pitch his puzzles around town, and like many Martlet writers before and after him, he headed to Monday Magazine.

With his crosswords already appearing in publications like the Victoria Star, Ashwood-Smith secured an agreement with the editor of Monday Magazine for eight puzzles to be published. However, Ashwood-Smith says that other staff at the magazine felt that the crosswords were trivial, and they were never published.

“‘Ah, why don’t you send something to the New York Times?’”

The editor returned the crosswords with apologies and compensation for his time. Dejected, Ashwood-Smith and his crosswords went to Demitasse, then a restaurant, where someone recognized the puzzles and asked him about them.

The interested party turned out to be the owner of Demitasse — a man named Marty who also liked crosswords. He was originally from New York, and had a farm on Galiano Island.

“He was a pretty good solver, so we used to compare notes,” Ashwood-Smith said. “I told him about Monday Magazine, and he said, ‘Ah, why don’t you send something to the New York Times?’”

“I said to him, ‘I can’t do that.’ He said, ‘It’s New York … just go.’”

Ashwood-Smith took the advice. Using his layout experience from the Martlet, he sent a professional-looking crossword to Eugene Maleska, the crossword editor of the NYT at the time.

It was accepted three weeks later, and published in June 1991 — just over a decade after Ashwood-Smith’s first crossword appeared in the Martlet.

“I was astonished that my first crossword submission to The New York Times (or anywhere) had been accepted,” Ashwood-Smith said in his NYT profile. “I still remember that morning in 1990 standing at my mailbox reading Eugene Maleska’s acceptance letter.”

From there, his skill as a crossword creator only grew. He became a full-time crossword creator for the Washington Post, and he now mostly freelances for USA Today and the NYT.

The crosswords

Ashwood-Smith’s crosswords are sometimes painfully difficult. He prefers to be published on Fridays, known as one of the hardest days of the week for the NYT’s crossword, and he is known by that publication as the king of the stacks — fifteen-letter clues that sit on top of each other, tough even for constructors to weave together coherently. (Check out the back page of the Martlet’s physical paper for a perfect example of both triple stacks and an almost-impossible quadruple stack.) He also writes his own books, the most recent of which is titled “Easy Freestyle Puzzles,” designed for beginner solvers.

He also recognized the community’s faults — there are far too few female crossword creators, he says often throughout our interview.

When meeting the Martlet for an interview, Ashwood-Smith spoke passionately about crosswords — when he saw the Martlet’s own iteration, he instantly began to solve and inquire about the clues and answers. He was quick to rattle off his favourite constructors (Erik Agard, Sam Ezersky) and each piece of history or information came with a well-crafted (if verbose) anecdote.

He is passionately embedded in the constructor community, and he joked about challenging himself to write more difficult crosswords than those around him. He also recognized the community’s faults — there are far too few female crossword creators, he says often throughout our interview.

But at the base of it all is the student newspaper with the beer money and the layout volunteers who would misprint his cryptic crossword clues (completely ruining any chance of getting the answer).

The future

Many crossword creators start the same way, Ashwood-Smith said, and while not all of them finish at the New York Times, it’s the same, basic sense of challenge and fun that runs between them. They’re pushing the envelope of how crossword puzzles are imagined by the general population.

“Crosswords did have a pretty bad reputation. You needed to really kind of know something particularly specialized to get into them,” Ashwood-Smith told me, referring to the “coded world of crosswords.”

That’s all changing as the field of creators diversifies in age, gender, and race.

“Modern crosswords, the ones you see — not just in the New York Times, but in good publications — are much more modern than they used to be,” Ashwood-Smith said. “They’re less arcane. They’re more relevant. Their vocabulary is more vibrant. There are more contemporary references . . . They’ve shed the cobwebs.”