In partnership with UVic’s ACET initiative, the former mining village is exploring how its underground network of abandoned mines could provide renewable heating and cooling

Photo by Jeffrey Bosdet via Douglas Magazine.

Cumberland, B.C., a village both literally and figuratively built on coal mining, has now partnered with the UVic-led Accelerating Community Energy Transformation (ACET) initiative to explore a clean energy resource from the abandoned mines the village sits on top of.

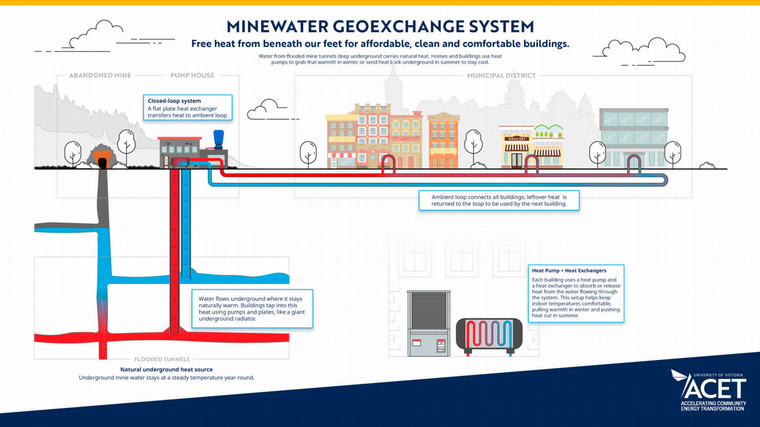

The network of mines below Cumberland, B.C. is flooded with trapped water, which is cooler in the summer and warmer in the winter than surface temperatures. According to the proposal, heat pumps could utilize water from the abandoned mines to provide both heating and cooling for buildings.

ACET says this solution is low cost, and has a near-zero carbon footprint.

ACET is a UVic-initiative that “collaborates with communities seeking to accelerate their energy transformation by co-creating equitable and resilient clean energy solutions.”

Dr. Zachary Gould, community energy planner and project lead, was brought on by his post-doctoral advisor in the early stages of this project. In June 2024, he visited Cumberland for their annual Miners Memorial Weekend, which Gould says “was a good chance to … really get to know the roots of the community and meet folks who have the deepest cultural connection to that history.”

Gould says that “the co-creation … is front and center,” on this project, and said that Cumberland Mayor Vickey Brown’s role in initiating the collaboration and leading the project from the beginning “speaks volumes”.

Through the first months of the project, Gould and his team worked with the mayor and her staff, along with community leaders and members, to define the scope and get a better sense of the data the village had about the mines. In this stage, they began to estimate what the potential resource really was, and what could potentially be done with it.

The water trapped in the mines stays fixed between 10 to 20 degrees Celsius, Gould said, which reliably splits the difference between heating and cooling temperatures year round. This means that, for buildings heated and cooled via heat pump, the village now has a source of water year-round, which could make the heating and cooling process more efficient.

Graphic by Steven Hession via the University of Victoria.

Gould explained that part of the plan includes a loop that circulates water through the district, and when buildings connect to that loop, they can either take heat from it or put heat back into it. If one consumer is pulling heat from the loop at the same time another is putting heat into the loop, both parties essentially cancel each other out, and “they both get free energy … at least in terms of the system,” Gould says.

If heating and cooling loads are balanced properly throughout the year, it will create a large opportunity for economic savings, as well as a much lower environmental cost. This system could replace the significant number of gas boilers that Cumberland currently relies on, resulting in a much more efficient system and lower electricity usage.

During the first phase, predicted to conclude next summer, the team aims to have a preliminary scope of what could be built, as well as to establish partnerships with all of the players that would be involved, such as engineering firms and landowners.

The next steps will include finding grants and other ways to fund an initial pilot-scale operation. The pilot will test this system on municipal buildings, to ensure that it can sustain the right amount of water flow and correct temperature for a longer period of time.

“Then,” Gould says, “the village would have confidence … that the resource can support the type of connections and new buildings that the village wants to connect to any district heating and cooling network.”

If this project is successful, there is potential for its application in other former mining communities across Canada. Gould has visited similar sites as a part of his early-research, such as Springhill, N.S., and he said “[A] next step could very well be quantifying … what potential impact it could have across Canada.”