Province plans to cap electricity, but critics warn water usage is being overlooked

Image by Township Planning via https://thediscourse.ca/.

Data centres are expanding across Canada, with the construction of at least eight large-scale centres underway in the country. Mark Carney’s Liberal government is planning to invest upwards of $700 million to support Canadian artificial intelligence (AI) projects. This follows the 2024 budget, which announced a $2 billion investment over the course of five years to support AI researchers and companies.

This year alone, the tech industry is expected to invest $400 billion into building AI infrastructure.

Adrian Dix — B.C.’s Minister of Energy and Climate Solutions — has proposed new rules for energy usage, which would prioritize natural resource manufacturing, and provide limits to how much electricity AI infrastructure could use. The province intends to open a competitive allocation process in January 2026, offering a maximum of 300 megawatts (MW) for AI projects and an additional 100 MW for data centres for the next two years.

According to the Canada Energy Regulator, B.C.’s capacity for electricity is 15 953 MW, meaning AI infrastructure and data centres will be limited to less than 3 per cent of the province’s electrical capacity. In 2024, BC Hydro’s demand was approximately 11 000 MW.

However, energy is only one concern critics of these projects have raised. Data centres also require large amounts of water for cooling.

In Canada, the already-approved AI data centers are expected to consume vast amounts of municipal drinking water.

A Microsoft data center in Etobicoke, Toronto has been approved to use up to 39.75 litres of water per second for cooling purposes, equal to roughly 1.2 billion litres of water per year.

Microsoft told CBC that Canadian data centers would not use as much potable water — water that has been treated and is safe to drink — due to specific design features that allow them to be cooled by outdoor air and rainwater.

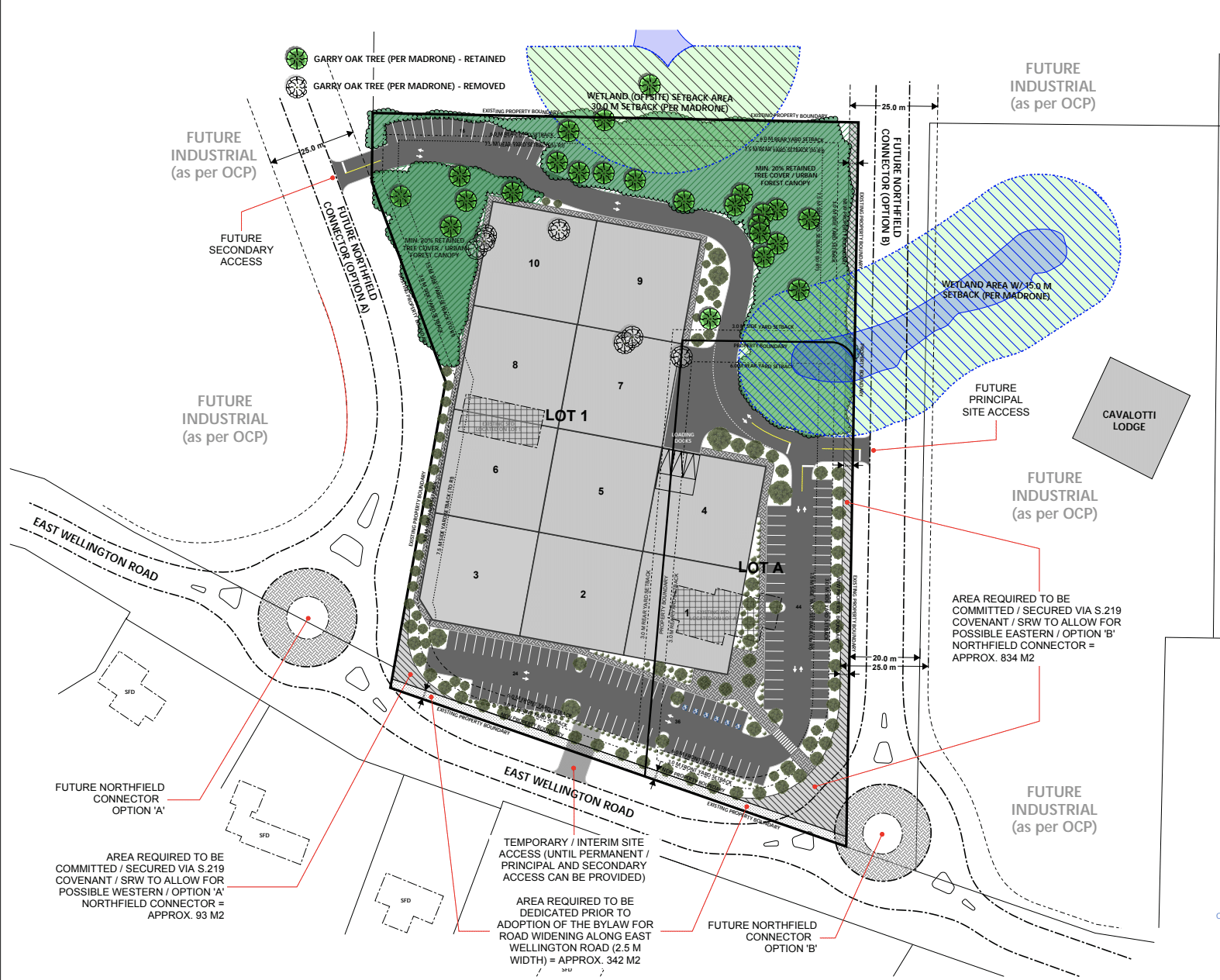

However, not all data centers being proposed employ these design features. Currently, a 200 000 square foot data center is being proposed in Nanaimo, B.C., which is not intended for AI use. As of publication, the exact purpose of this data centre is unknown.

A 200 000 square foot data center has the potential to go through 70 000 litres of potable water per day. A study by the International Energy Agency estimated that data centers globally consumed approximately 140 billion litres of water for cooling in 2023 alone.

According to the B.C. government’s water-saving tips for residents, saving 70 000 litres of water would require a single B.C. resident to take five minute showers for almost 26 years straight.

The City of Nanaimo states this data centre’s water usage will peak at 69 000 litres of water per day.

Much of the water used by data centers is potable water, taken from municipal utilities, since untreated water can damage the computer equipment.

However, the data centre proposed in Nanaimo will reportedly use a closed-loop system — a type of cooling process where the water is reused and recirculated.

The Martlet spoke with Dr. Deborah Curran — the Executive Director of UVic’s Environmental Law Centre, and a cross-appointed professor in the Faculty of Law and the School of Environmental Studies.

Curran told the Martlet that closed-loop systems are better from a water perspective, as they result in minimal loss of water. However, closed-loop systems could require more energy, Curran said, because the water needs to be cooled in the summer and in times of high heat.

Not every data centre proposed in B.C. is guaranteed to operate on a closed-loop system. At Thompson Rivers University (TRU) — a post-secondary institution in B.C.’s interior — Bell Canada is launching an open-loop AI data centre. Bell Canada claims the excess heat will be repurposed to heat buildings on campus. However, this does not address the water issue, since open-loop systems rely on evaporating water for cooling.

Critics of AI data centers have said Canada is rushing into these projects with few protections to its water supply.

One 2023 study found that 10-50 medium sized responses from ChatGPT, the popular generative AI program, could consume roughly 500 millilitres of water.

According to Curran, land use decisions in the province are often not adequately assessed for the water demands a project requires.

Curran said that some parts of the province — such as the east coast of Vancouver Island and the Okanagan — already have all available surface water fully allocated for different uses.

According to the Canadian Climate Institute, 40 per cent of the planet is expected to experience year-round drying over the 21st century, and already parts of the province — such as the interior — are experiencing abnormal droughts.

Curran told the Martlet that local governments in B.C. have the ability to shape and regulate water use to allocate it as they see fit, but aren’t good at responding to new high water use projects.

“A household of four people to an industrial user that’s going to contaminate the water and store it on site [are treated] virtually the same. We need to come to a much more nuanced and specific approach to water use, especially as we increasingly move towards scarcity,” she said.