After a year of silence, Divest UVic is back. We checked in with what they have planned for the coming year, the history of divestment at UVic, and the strategic coordination by Canadian universities to manage divestment campaigns.

In 1896, Swedish scientist Svante Arrhenius found that the burning of fossil fuels may lead to higher carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere, consequently causing global warming.

In 1962, Rachel Carson published the monumental environmental science book Silent Spring about pesticides, raising awareness on the effects humans can have on the environment.

The environmental movement of the global north was born in the early 1970s, with the world celebrating the first earth day in 1970 and activists establishing Greenpeace in 1971.

In 1992 in Rio de Janeiro, 154 nations signed the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), a treaty that called on the world to act on global warming and climate change.

In 1997, the Kyoto Protocol was adopted in Japan, which outlined countries’ restrictions on carbon emissions, binding under international law.

In 2015, countries met this time in France to ratify the Paris Agreement, promising to keep the world’s temperatures to 2°C above pre-industrial levels, and to limit the increase to 1.5°C in order to avoid the catastrophic effects of climate change. To date, 184 countries have ratified the agreement, including Canada.

In December 2018, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), a scientific body that provides research and advice on the consequences of climate change, gave the world an ultimatum: We have 12 years to prevent global temperatures from rising 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, otherwise we will experience unprecedented extreme weather — and all of the socioeconomic, political, and environmental consequences that come with that.

And a few days later, at a small university on Vancouver Island, students Juliet Watts, Gillian Wiley, and Lena Price reignited a movement that many may have forgot existed: Divest UVic.

Divest UVic is a group that aims to lobby the university, and specifically the UVic Foundation (the independent group charged with managing and investing the university’s $440 million in assets), into freezing any further investments in fossil fuel companies and redirecting all existing investments in fossil fuel companies over the next three years.

But what does the university’s investment strategy have to do with global warming and climate change? According to one University of Victoria representative, not a whole lot.

“I’m curious,” said Paul Marck, UVic’s Associate Manager of Public Affairs, when the Martlet approached him for information on the university’s investment strategy. “Is there some recent event, call to action, or something tied to divestment that’s new? I’m doing my diligence on this topic and frankly am having trouble reading the landscape for anything current that the movement is pegged to.”

It sounds like UVic hasn’t heard the news and it looks like we’re the ones who are going to have to break it to them.

Dear UVic: it’s not us, it’s you. And it’s time to break up with fossil fuels.

THE QUEST TO DIVEST

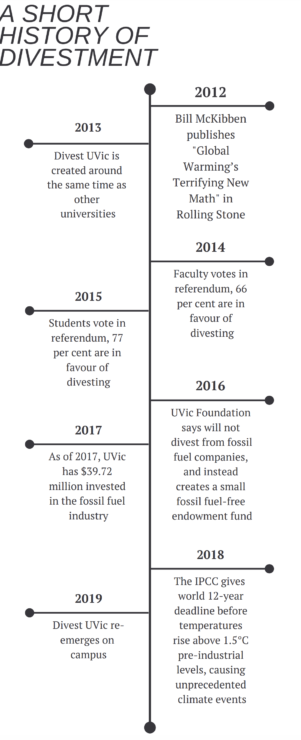

Although the Divest UVic movement was only recently brought back to life, the group has actually been around since 2013, founded around the same time as groups at other Canadian universities such as Dalhousie and the University of Toronto.

In 2013, divest groups were appearing all over the Global North, sparked by a series of events — including an article by environmentalist Bill McKibben, published in a popular magazine that we don’t often associate with the environment: Rolling Stone.

The article was called “Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math” and outlined the seemingly impossible dilemma of global warming and climate change. But it also reminded readers of a successful civil society campaign that dated back to the 1980s: the anti-apartheid movement.

The article was called “Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math” and outlined the seemingly impossible dilemma of global warming and climate change. But it also reminded readers of a successful civil society campaign that dated back to the 1980s: the anti-apartheid movement.

McKibben noted that this movement began at college campuses in the United States, and that by the end of the 1980s, 155 campuses had divested from companies doing business with South Africa.

McKibben’s article gave students a clear motive: “If [students’] college’s endowment portfolio has fossil-fuel stock, then their educations are being subsidized by investments that guarantee they won’t have much of a planet on which to make use of their degree.”

Universities have traditionally been a hot spot for activism. Along with the anti-apartheid movement, the civil rights movement of the 1960s, the 2010 Arab Spring, and the Venezuelan protests of 2014 all grew on university and college campuses.

♥

Divest groups are growing in universities across Canada, including at the University of Ottawa, Simon Fraser University, and McGill. Laval University in Quebec has already fully divested, and many Ivy League universities including Stanford, Oxford, and Yale are headed in the same direction.

♥

Why? Because students are energetic, passionate, and not yet cynical. They are young enough to visualize a better world for themselves and their children, and remain hopeful that change is still possible.

The divest movement at UVic was a powerhouse in 2014 and 2015. They had several meetings with university administration, including the UVic Foundation. UVic faculty had their own divest movement, and sent an open letter to President Jamie Cassels and the UVic Foundation to divest from fossil fuels. In 2014, UVic faculty held a referendum where 66 per cent of participants voted in favour of divesting. In 2015, the student body held a referendum in the student society elections and 77 per cent of participants voted in favour of divesting.

But in a university setting, there is a high turnover of faces. People graduate, and there aren’t always the human resources to pick up where they left off. The pillars of civil society movements are the people behind it, and without motivated organizers, things can fall through.

Since last January, Divest UVic has been on the backburner. But now, a group of students including Watts, Wiley, and Price — all in second year — have decided to take over, and they seem to have picked the right time to do it.

Divest groups are growing in universities across Canada, including at the University of Ottawa, Simon Fraser University, and McGill. Laval University in Quebec has already fully divested, and many Ivy League universities including Stanford, Oxford, and Yale are headed in the same direction.

The movement is gaining traction at a time when any institution — university, government, financial — must act as a leader in the face of the greatest challenge of our lifetime. The question is, will UVic be a leader or a follower?

ENVIRONMENT VS. ECONOMY

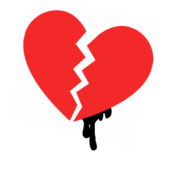

The individuals that have bred and fostered climate change denial, and then climate change apathy, have been incredibly successful at separating the environment from the economy. These two forces have been so well-pitted against each other that we still hear this trope touted by politicians from all sides of the political spectrum: the environment is all very well, but we have to think about the economy. The economy.

The individuals that have bred and fostered climate change denial, and then climate change apathy, have been incredibly successful at separating the environment from the economy. These two forces have been so well-pitted against each other that we still hear this trope touted by politicians from all sides of the political spectrum: the environment is all very well, but we have to think about the economy. The economy.

And sure, in the very short-term, if we are to discount the environment and go buck wild on fossil fuel expansion, the Canadian economy would likely boom for a couple of years — and this hypothetical is ignoring the amount of civil action alive in Canada today and the precedents that continue to be set in the Supreme Court, where the stalling of fossil fuel infrastructure expansion seems almost inevitable.

But we don’t even have to go that far. If we look to the short term — and even the present — it is now apparent to most economists, governments, and international bodies that the environment and the economy are deeply connected.

“This is not something that’s just a West-Coast-UVic-Wants-To-Divest-Thing,” says Watts, speaking to the Martlet about Divest UVic.

“The World Economic Forum recently said that the policy failure of mitigation [and] adaptation of climate change and … unpredictable weather events are the world economy’s biggest top two risks.”

It’s not just the World Economic Forum. The World Bank estimates that climate change will cause a migration of as many as 140 million people by 2050, a climate report published by the United States government predicts the American economy will be reduced by 10 per cent by the end of the century due to climate change, and according to reinsurance company Munich RE, in 2018 alone, natural disasters and extreme weather wreaked $160 billion in damage worldwide.

“It’s not just a social problem,” says Watts. “It’s an economic problem.”

UVIC’S HYPOCRISY

James Rowe, an associate professor in UVic’s School of Environmental Studies, joined the first Divest UVic faculty group in 2013 because he felt he wasn’t walking his talk in the classroom.

“It’s hypocritical to be communicating to students about the clear and present danger of climate change and the need for action when my own pension fund … is materially invested in those very companies that … we should be challenging,” he says.

Rowe says that the university should also reflect on its own hypocrisy.

“This campus positions [itself] to the wider public as a climate change leader, and yet it’s still trying to profit from companies that have histories of sowing doubt on climate change [science].”

Claire O’Manique, who became involved with Divest UVic in 2016 during her Masters program, also observed how UVic makes a strong effort to outwardly appear as a climate leader.

♥

As of 2017, UVic had $39.72 million invested in the fossil fuel industry.

♥

“There is definitely a lot of irony in their ‘on the edge’ … advertising slogan, especially because a lot of it does have to do with climate research,” she says. “They really do put that [image] out in the media.”

On Jan. 10, UVic opened its new Oceans-Climate Building at Queenswood to help improve ocean and climate research.

“UVic is a leader in research on climate modelling, mitigation and adaptation, the development of sustainable energy systems, and the human dimensions of climate change,” reads a Jan. 8 UVic news release.

Yet UVic still has millions invested in fossil fuel companies. As of 2017, they had $39.72 million invested in the fossil fuel industry. One substantial investment is in Imperial Oil, a company owned almost entirely by ExxonMobil.

Since 1998, Exxon has spent over $33 million in attempts to silence climate science.

“Exxon is just such an egregious example of climate change denial and the fact that we’re still trying to profit from them is dubious,” says Rowe.

The irony extends further. 30 per cent of the UVic Foundation’s annual budget goes to the Pacific Institute for Climate Solutions (PICS), an organization that “shares a global vision of net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by mid-century.”

When the Martlet asked Andrew Coward, Treasurer of the UVic Foundation, if he recognized the irony of investing in fossil fuel companies while also allocating a large portion of their budget to research on climate change, a straightforward answer was difficult to decipher.

Illustration by Austin Clay Willis, Design Director.

“We asked our investment managers [in 2016], if we exclude energy from our investment portfolios, would this affect our rate of return expectations?” says Coward.

“They said [that] if [we wanted] to exclude subsects of the market, then we should re-evaluate [our] rate of return expectations. So from a trustee perspective, it was clear this was not something we could do as fiduciaries.”

Beyond the contradictions on climate science, Rowe notes that it’s hypocritical for the university to be touting its progress on Indigenous reconciliation while upholding these investments.

“They also position themselves publicly as a leader on reconciliation and yet similarly are making investments in the very companies that nations are fighting with over their territories,” he says.

“By investing in companies that are seeking to despoil [Indigenous] territories, it’s unconscionable, and it’s another point of hypocrisy.”

♥

“For UVic to say that they’re going full throttle towards reconciliation while pumping money into companies that are going full throttle trying to break through [Indigenous] people’s territories is absolutely ridiculous.”

♥

Wiley and Watts agree that UVic can’t have the best of both worlds.

“Just like … the rest of UVic’s sustainability claims … it’s hypocritical for UVic to claim that they are focused on reconciliation and working towards that while carrying these huge investments in companies … that are going to have a huge impact on Indigenous communities,” says Wiley.

Watts expands on this: “For UVic to say that they’re going full throttle towards reconciliation while pumping money into companies that are going full throttle trying to break through [Indigenous] people’s territories is absolutely ridiculous.”

“Even looking at what’s happening [at] Unist’ot’en right now, that is a direct result of fossil fuel investments,” she says.

Watts is referring to the conflict surrounding the fossil fuel infrastructure expansion on Wet’suwet’en First Nation territory in northern British Columbia. On Jan. 25, a subsidiary company of TransCanada bulldozed a trapline at the Unist’ot’en camp on Wet’suwet’en territory during construction on the pipeline.

Beyond affecting Indigenous subsistence methods, the toxic fumes and runoff that naturally come with oil and gas development can cause sickness in nearby communities, says O’Manique. Meanwhile, the profits reaped from the industry are often channeled into the pockets of corporations.

“The Lubicon [First Nation], they’ve had like $14 billion worth of oil extracted from their territory and yet they don’t have clean drinking water,” says O’Manique.

“The cancers that members of that nation face just from being exposed to everything there is quite devastating and drastically different than anywhere else.”

WHY WON’T UVIC DIVEST?

Despite widespread dissent from students and faculty in years past — as expressed through faculty’s open letter, the two referendums, and consistent protests — UVic still refuses to sign its fossil fuel divorce papers.

“We remain abreast of the news and of what others are doing, and we have decided to maintain the stance since 2016,” says Coward. “It’s quite clear that our fiduciary duty ensures that we have to act like a prudent investor and act in the best financial interest of the fund.”

O’Manique, meanwhile, understands the need for the university to be a prudent investor, but is wary about UVic’s operation as a business.

“One of the biggest things I’ve learned from divestment is seeing how neoliberal Canadian universities are, or just how much they’re run like a business,” she says.

Curious about UVic’s business plan, O’Manique did some research into investments from 2013 to 2017 and found that the university wasn’t even generating revenue from some of the companies, such as Husky and Imperial Oil.

“It’s interesting because [their fossil fuel investments] are not performing as well compared to their other investments,” she says.

“What we heard from the charitable Foundation was they make these [investment] decisions from an economic standpoint and that’s what their role is … and so it’s interesting because even from an economic standpoint they’re not safe investments anymore.”

♥

Although UVic started a fossil fuel-free fund in 2016 for alumni who want to donate but not contribute to fossil fuel companies, Divest UVic is skeptical of how green that fund truly is. They also note that the fund was borne out of just $25 000, while the amount invested in fossil fuels as of 2017 is $39.72 million. That’s 0.06 per cent of the amount invested in fossil fuels.

♥

Coward, however, says UVic is looking at investment returns long-term, not just from 2013 to 2017.

“When you look at investment return, they’re very time-date specific, and so as a long-term investor, the managers that we hire look at investments on a long-term perspective,” he explains.

But a long-term relationship with fossil fuels isn’t feasible with the fast-shifting political and environmental landscape, says UVic alumnus Emilia Belliveau, whose Masters research focused on climate justice in the fossil fuel divestment movement.

“We have 12 years to drastically change and restructure how we can consume and produce energy,” she says. “And so whether you’re looking at an immediate year-by-year loss from the crash of coal a couple years ago, or looking at a more long-term future — 10 years, 50 years — it doesn’t matter. Either way eventually the fossil fuel industry … is not going to be stable.”

Watts, Wiley, and Price have looked into alternative low-carbon investments, and found that many of those were actually getting better returns. Watts expressed her frustration that UVic isn’t seeking greener pastures to invest in.

“What we’ve seen from the numbers … from some of the other ethical firms are that they have way higher returns on these new green technologies, and other … socially and environmentally ethical organizations do way better,” she says. “They’re losing money on these investments in dirty oil.”

Although Coward says that in 2016 the Foundation’s investment managers told them their rate of returns would be affected if they were to divest, Rowe says he met with UVic President Jamie Cassels and the Foundation on several occasions around that same time, and that UVic understood the economic safety of divestment — and that was three years ago.

“In one of the meetings that we had, one of the main things that got communicated is that they’re aware that financially it would be fine to divest, that it’s not going to harm the portfolio,” says Rowe.

They know that divesting is either the right move or that it at least wouldn’t be a destructive one, he says.

So if the hesitation isn’t due to economic reasons, why is UVic idling?

“A concern that [was] raised is that they see divestment as acting politically,” Rowe says.

“The point that we made was that they don’t invest … in munitions, for instance, or tobacco, and so obviously they’ve made some political determinations there, so why not fossil fuels?”

♥

“There’s been talk of opening a legal strategy… As a faculty member who’s going to draw funds from my pension, I would have the legal standing to sue the Pension Board for poor financial management for not addressing climate risk.”

♥

UVic’s response at the time of these discussions was that fossil fuels have yet to receive the same amount of public scorn as munitions and tobacco, says Rowe.

“Divestment has found easier traction in jurisdictions where the political economy is not reliant on fossil fuels,” says Rowe. He adds that jurisdictions like Quebec, California, and New York State, which are less embedded in fossil fuel economies, have had universities divest successfully.

Although Coward can’t speak to any such conversation, he does note this reliance on fossil fuels. “Canada [is] a very resource-intensive industry, and the stock market [is] as well.”

Rowe doesn’t think the UVic Foundation can escape being political at this point.

“If you’re investing in Exxon, that’s politics. You’re choosing a side,” he says.

Belliveau, meanwhile, thinks these investment politics come down to personal relationships.

“The sense that I’ve gotten from talking with administrators is that it’s not just about maintaining the status quo, but that actually they have personal relationships with the fund managers,” she says.

“They’ve been working with them for a long time so they don’t want to tell them what to do, less for financial reasons and more because of the social and political dynamics that that creates between their golfing buddies.”

Coward makes no mention of any personal relationships between UVic Foundation members and the investment managers, only noting the trust UVic places in them.

“We rely on [our investment managers] to make the best investment decisions for us in terms of equity and debt and that sort of fixed-income investment,” he says, noting, however, that they do “[monitor] closely underperformance or overperformance and then … ensure that we ask hard questions of our managers of why they’re holding certain positions if they’re underperforming.”

While the UVic Foundation feels their portfolio is safe in the hands of their fund managers, Rowe thinks that with climate change looming, we can’t cling to the comfort of the status quo.

“I think [the] divestment [movement] has been really effective in helping to move the needle but the culture hasn’t moved enough for leaders to feel safe… My critique would be if you’re trying to play it safe, that’s not leadership.”

WHERE’S THE ACCOUNTABILITY?

When O’Manique tried to track down who was in charge of making UVic’s investment decisions in the past, she had a tough time following the strings.

“There’s just no accountability anywhere in this system. And it’s not even the people themselves in any of these roles, but at no point is there a specific group [that takes responsibility],” she says.

“The Board of Governors say, ‘It’s the Foundation,’ and the Foundation says, ‘Oh, it’s the Board of Governors, and it’s our accountants, who we only meet with once a year and we have so many things to go over.’ So there’s no clear link in any of it and their mandates are to keep it as a business.”

Indeed, Coward tells the Martlet that investment choices aren’t made by the Foundation but by fund managers.

“We use external money managers, and they report back to us monthly, quarterly,” he says.

“They’re the ones that make those decisions, and they’ll make those decisions on a day-to-day basis.”

Belliveau believes this finger pointing is a deliberate way to avoid accountability.

“[It’s] such a cop-out because really the university is hiring these financial managers … and they’re using the advice of financial managers who are used to status quo investing and who are part of this ideology where it’s purely about profit and social value isn’t counted. They’re using those managers as cover to remove accountability,” says Belliveau.

The Martlet asked Coward if he has heard of Blue Heron Advisory Group, a portfolio system that has no investments in fossil fuel extraction companies. This is one investment portfolio that members of Divest UVic raised as a potential alternative for the Foundation’s current portfolio. Coward says that he is aware of Blue Heron, but when asked if the Foundation would ever consider hiring someone from the group, he said he could not speculate.

“We have a robust process for hiring investment managers,” he says.

STRATEGIC COORDINATION BETWEEN UNIVERSITIES

While avenues like meetings, protests, and referendums have been largely exhausted by Divest UVic organizers in the past, a new surge of student activism is astir in the romantic February air.

“In the next couple of weeks leading up to Valentine’s Day, we’re going to be [doing] a letter-writing event called ‘Breaking Up With Fossil Fuels’,” says Wiley.

She says the letters will be addressed to the Board of Governors to show them that if they want any affection this Valentine’s Day, they’re going to have to earn it — by divesting.

“[It is] a way to kick off re-starting the movement and reopening those lines of communication,” Wiley says.

The idea is inspired by UBC’s #breakingupwithbigoil media campaign.

Cross-campus communication and tactic-sharing will continue to be a focus in the weeks and months to come.

“We’re working with UBC and SFU, but I think we’d even like to expand that farther to other universities across the country and to have days of action where every university demonstrates their students want this, that every student across the country wants this,” says Watts.

Divest UVic has already learned a lot from these partnerships, including how cross-campus communication between university administrations can work in their favour as well.

“What we’ve heard from UBC and SFU is that the universities themselves — the administrations — talk to each other about what kind of actions the students are taking,” Watts says.

“They really watch what each other are doing in terms of divestment. So as soon as one of them moves a little bit — especially in B.C. with SFU and UBC — UVic is influenced by them.”

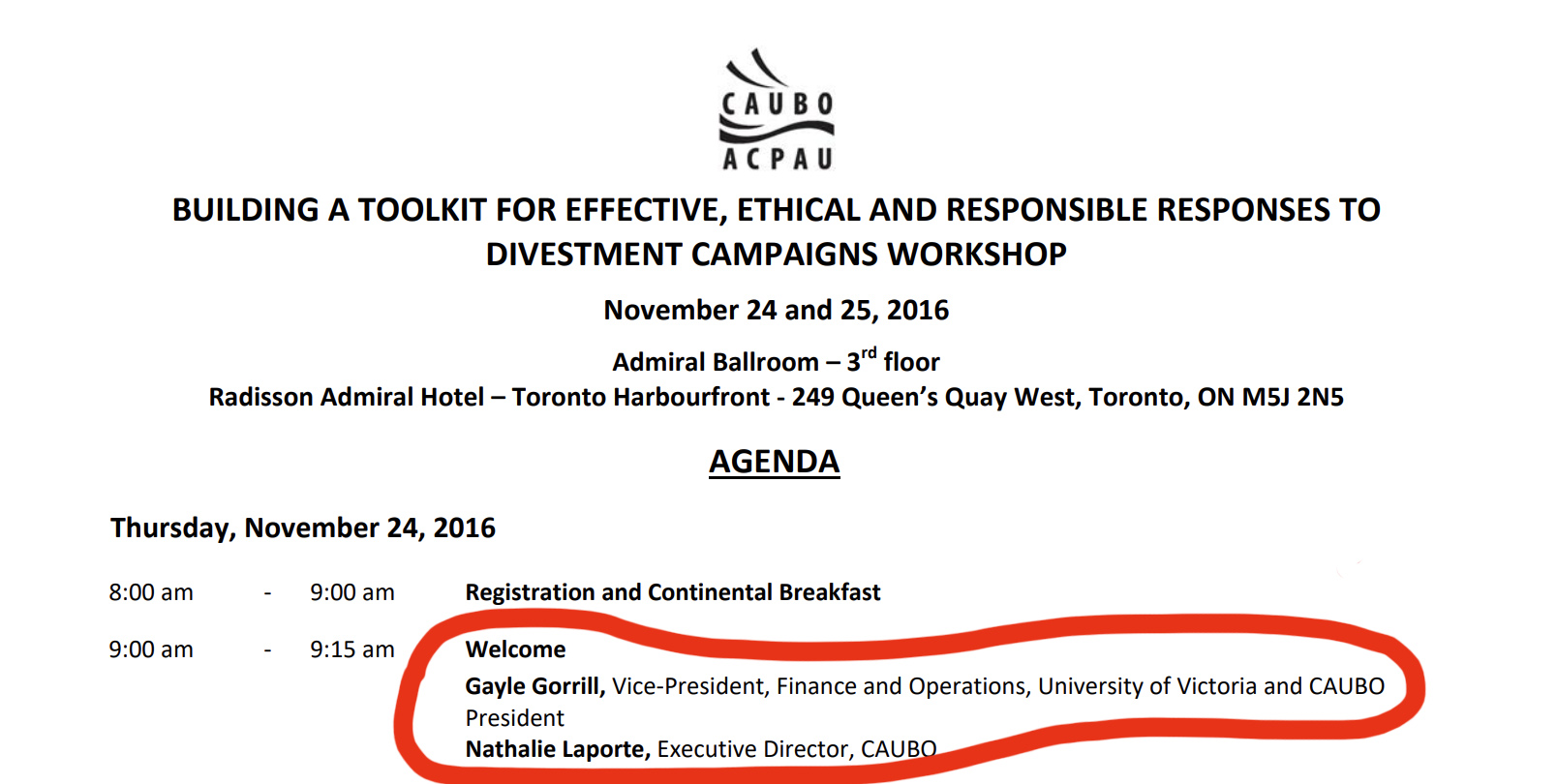

And university administrations have certainly been talking to each other about divestment, including sharing knowledge about how to respond strategically to divestment campaigns.

In November 2016, Belliveau says UVic attended a workshop hosted by the Canadian Association of University Business Officers (CAUBO), whose mission is to connect university administrations to create solutions for shared issues. The workshop was called “Building a Toolkit for Effective, Ethical, and Responsible Responses to Divestment Campaigns.”

Although Coward couldn’t speak to the 2016 workshop, (only mentioning that UVic hosted a balanced forum on the subject of divestment in 2015), the workshop’s agenda shows that Gayle Gorrill, UVic’s Vice-President of Finance and Operations and the Foundation’s President — who also happened to be the CAUBO President at the time, and now serves on its board of directors — gave both the welcoming and concluding remarks at the event.

The conference summary report provides a series of cautionary recommendations for universities facing divestment campaigns, and notes that divestment can put donor relationships and research funding at risk.

The report also advises universities that divestment won’t be very effective in addressing climate change.

“University divestment from fossil fuels was seen as being a limited means of effecting climate change action,” the report states.

“The amount of university capital invested in fossil fuel holdings is not substantial enough to have a market impact if divested,” it adds.

The report recommends proactive measures for dealing with reconciliation issues as well.

“Continually monitor to know what might be coming next. New issues such as truth and reconciliation with our Indigenous communities are on the horizon. Prepare for the next issue before it emerges.”

♥

“[These documents] were likely not supposed to come into our hands … but they are very revealing. The language is formal and non-explicit, but it is a coordinated strategy to block divestment campaigns.”

♥

Former members of Divest UVic also provided the Martlet with an accompanying case study, where UVic served as the example, called “CAUBO Divestment Case Study: University of Victoria.” The case study summarizes how UVic has worked to address divestment requests.

“[These documents] were likely not supposed to come into our hands,” says Belliveau. “But they are very revealing. The language is formal and non-explicit, but it is a coordinated strategy to block divestment campaigns.”

One question in the case study asked to UVic by CAUBO seems to highlight the intent of the study.

“What lessons did you learn from your experiences that would benefit other university administrators facing divestment campaigns?”

Whether UVic monitors their actions or not, the Divest movement has no intention on slowing down. Divest UVic plans to reach out to Laval University to see how students successfully pressured for divestment, and where the university chose to reinvest its money, says Watts.

Another pressure point being discussed is the involvement of UVic’s alumni community, says Wiley.

“Alumni donations are a really important thing for the university, and so mobilizing alumni for the movement and having that financial incentive for the university to look at divestment is really impactful,” she says.

With Alumni Week happening from Feb. 1 to 7, the group will be attending events and speaking with alumni, encouraging them to sign a pledge threatening to halt their donations until UVic commits to divestment.

Although UVic started a fossil fuel-free fund in 2016 for alumni who want to donate but not contribute to fossil fuel companies, Divest UVic is skeptical of how green that fund truly is. They also note that the fund was borne out of just $25 000, while the amount invested in fossil fuels as of 2017 is $39.72 million. That’s 0.06 per cent of the amount invested in fossil fuels.

On the faculty side, Rowe has some ideas brewing as well.

“There’s been talk of opening a legal strategy,” he says. “As a faculty member who’s going to draw funds from my pension, I would have the legal standing to sue the Pension Board for poor financial management for not addressing climate risk.”

A QUESTION OF LEADERSHIP

Investments aside, UVic maintains it holds a leadership role in climate change research and solutions.

Beyond the new Ocean-Climate Research building, UVic announced its new sustainable housing project, which will begin construction in 2020.

“Design and construction will meet both Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) and Passive House standards, a rigorous world standard that is a first for UVic,” reads one UVic news release.

Coward says a portion of the funding for the $201 million project will be loaned from UVic’s investments.

“The Foundation committed to investing 10 per cent of the fund into the new student housing,” he says. “That’s roughly $40 million.”

“They’ll be built to the Passive House standard. Even in adding 600 beds, it’s expected that the greenhouse gas emissions footprint of the university will remain flat.”

But Belliveau says UVic’s leadership is two-fold: a leader of solutions, but still a leader of the problem.

“Some of those concrete, on-the-ground building changes are really exciting to see,” says Belliveau. “But if we’re still continuing to directly invest in companies that are extracting fossil fuels, that are displacing Indigenous peoples in order to do so, that have long histories of climate denial, … we can’t be fooling ourselves and think that somehow … we’re part of the solution but not also part of the problem.”

With the reinvigoration of Divest UVic and the IPCC’s 12-year deadline serving as a global call to action, the possibility of UVic divesting is not out of the question.

In 2015, Coward is quoted to have said, “We share [Divest UVic’s] concerns about climate change … We just don’t necessarily believe that divestment is the best approach.”

In 2019, the Martlet asked Coward if he stands by that statement.

“We stand by that statement as of 2016, and we’re happy to consider any new material information that could potentially change that stance,” he says.

Change is possible, especially for a university that’s already branded itself as a leader.

“UVic considers itself a leader among Canadian universities for the actions [in environmental sustainability and responsible investment] it has undertaken,” said Marck, the same UVic representative mentioned at the start of this article.

The university may consider itself a climate leader, but Divest UVic certainly does not — and they don’t plan on staying quiet about it.

Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed, citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has. -Margaret Mead

CORRECTION: In the print version of this article, pertaining to the graphic “A short history of divestment,” under the subheading “2016,” the Martlet wrote that UVic established a fossil fuel endowment fund. This was supposed to say UVic established a fossil fuel-free endowment fund. We deeply regret the error, and will be issuing a written correction in our next issue on Feb. 21.