It has been 17 months since B.C.’s provincial health officer declared a public health emergency regarding the prevalence of fentanyl-related overdoses and deaths. In that time, B.C. has seen hundreds of overdose deaths. July 2017 saw 91 suspected drug overdose deaths in the province—the equivalent of nearly three deaths every day — at a rate 30 per cent higher than in July 2016. Those working in the area of harm reduction identified that overdoses in the province were reaching crisis levels well before then, says Bruce Wallace, assistant professor at UVic’s School of Social Work and collaborating scientist with the Centre for Addictions Research of BC (CARBC).

Victoria is one of the three cities in the province with the highest number of illicit drug overdoses this year, along with Vancouver and Surrey. Such statistics can be frightening, and in the face of this national public health emergency, it begs the question of what we can do to help combat this crisis at home.

Naloxone training

Participating in naloxone training is arguably the easiest way for students to protect themselves and their friends from opioid-related overdoses. Naloxone is a drug that blocks or reverses the immediate effects of narcotic overdoses (such as slowing breath and loss of consciousness). It can be administered with a needle into the muscle of the upper arm, upper leg, or buttock. Naloxone is not intended to replace emergency medical care for an overdose and only lasts for 30–90 minutes.

On August 31, more than 250 people participated in events downtown marking International Overdose Awareness Day (IOAD). Hosted by the Society of Living Illicit Drug Users (SOLID) and AIDS Vancouver Island, the Victoria public was able to receive free overdose prevention and response training and free naloxone kits. 262 kits were handed out over the course of the event.

“It’s really important for people to go [to events like IOAD] because there are a lot of people who use drugs, there’s a lot of stigma around it, [and] there’s a lot of hidden drug use,” says Trish Pal, support coordinator at the Anti-Violence Project (AVP). “Naloxone is super safe. If you had a naloxone kit with you and you suspected that somebody was overdosing — they’re unresponsive, they’re not breathing, but they still have a pulse, all these symptoms of a drug overdose — and you give them naloxone, it won’t hurt them. It doesn’t do anything if you don’t have opiates in your system.”

Students can buy naloxone kits from the pharmacy in the SUB, or they can also book a “Kit Appointment” with health services to receive a free kit and learn how to use it. If this appointment is booked, it is not added to that student’s medical records.

As part of the UVSS’ Safe Use Campaign, there will also be two naloxone response trainings held on campus in September (Sept. 20 and 21) and one every month for the rest of the school year (until April). While these training sessions are free of charge, space is limited to about 30 participants. UVSS Director of Campaigns and Community Relations Anmol Swaich is hopeful that each session will reach capacity.

“It’s important for students to go to this kind of training because you don’t necessarily know what life is going to throw at you,” says Swaich. “You don’t know what situation you might end up in. And just the reality is that substances now often have fentanyl, and all types of substances have fentanyl — I think the only thing they haven’t found fentanyl in so far is marijuana. And just being prepared and being ready to deal with whatever situation might arise is really important for students, because at the end of the day, if you have naloxone training and you’re in that situation, you might end up saving a life.”

“I’m not sure if there’s been an overdose [on campus] related to fentanyl . . . but I believe there have been overdose incidents on our campus. That has happened,” adds Swaich.

According to a B.C. Coroners Service report, 81 per cent of illicit drug overdose deaths in 2017 have involved fentantyl (either alone or in combination with other drugs).

As such, naloxone training should be considered by everyone, Wallace says.

“Naloxone training shouldn’t be about social profiling and figuring out when you’re around people who are at risk of overdose or not,” he says. “It’s a universal precaution that we should all be trained [in], all be carrying, and all be able to use — similar to other life saving technologies like emergency first aid.

“[Whether] somebody is a downtown office worker or social worker downtown or a student at UVic, I think the priority is there regardless.”

However, he warns, naloxone is a limited response. It is imperative that we are not only responding to overdoses, but preventing them before they occur.

“Naloxone is about responding to overdoses after they’ve occurred. And I think what we know clearly in this emergency is that we want to be more upstream and actually provide interventions and support to prevent overdose, not just respond after the person has already overdosed and is at risk of death and brain injury.”

Above all else, Pal emphasizes caution.

“Even if you bought from a trusted dealer, you don’t know what’s in your drugs these days. People are dying thinking they’re using cocaine, and they’re dying from fentanyl overdoses. Having a naloxone kit and knowing how to use it is imperative. Harm reduction is imperative. Making a plan for what happens is imperative,” says Pal.

Drug checking

“There’s an incredible amount of overdose deaths,” says Pal. “I think the amount of overdose deaths is higher in B.C. than it’s ever been. There [are] opiates in everything right now. Acid . . . MDMA . . . people are taking fentanyl and they don’t know that they’re taking it. And so, I think that there’s a lot of party drugs that happen on campus, even though I think UVic doesn’t want to admit that. There are a lot of students who use party drugs, and if we know how to take care of each other, then we’ll be a lot better off.”

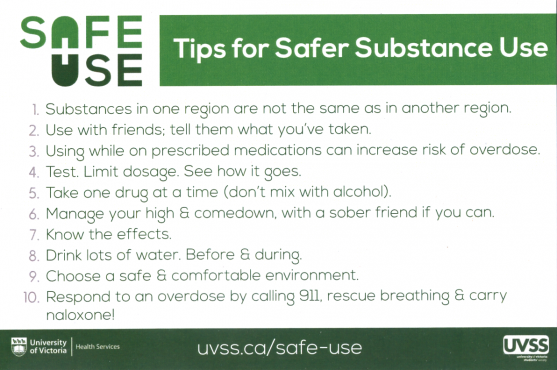

This void in discourse and information is what led to the UVSS’ Safe Use campaign.

“With everything going on with the opioid crisis, just the reality that students do use [drugs] on campus, we just figured that this was a really important campaign, to try to reach students wherever they are in their lives, whatever is going on, try to provide access to resources and support, in whatever way we can,” says Swaich. “This was definitely an area that was lacking on our campus.”

While UVic students can’t get their drugs tested on campus, Pal, Wallace, and Swaich all recommend using the STS Pain Pharmacy downtown. Students are also allowed to go to pop-up supervised injection sites . The B.C. Coroners Service report notes that there have been no deaths at supervised consumption or drug overdose prevention sites in the past ten years.

“It’s important for students to go to this kind of training because you don’t necessarily know what life is going to throw at you,”

Drug checking (through the use of fentanyl strips) also plays a central role in harm reduction. The strips work when a small amount of the substance in question is placed in a small dish and combined with water. The paper testing strip is dipped into the solution and stirred. Two lines will appear on the strip if the substance is clear of fentanyl. One line will appear if fentanyl is present. Wallace warns, however, that these checks come with limitations.

“It is a pretty blunt instrument for drug-checking,” he says. “It only does say if there is a presence of fentanyl in a check and it doesn’t say the potency. It’s a significant limit.

“The other limit is that fentanyl has unique challenges to detect in the processes,” Wallace explains, “because depending on the type of substance — the powder, the pill — the fentanyl might not be evenly distributed throughout the substance that’s being checked. A check on one part of the sample might not reflect the full substance. So that’s a significant risk, when there’s a portion of the substance that does include fentanyl, it might be detected or it might not be detected . . . and there’s a real risk of false positives and false negatives with the current checking.”

This lack of sophisticated detection technology is precisely what Wallace is hoping to address with his research. He is working alongside Dr. Dennis Hore in the UVic Chemistry department to pursue alternative approaches to provide more effective drug checking.

“Dr. Hore and I have three proposals under review right now to try to develop innovative technologies around drug checking to be able to engage people who use drugs in the research, and to investigate what’s worked in other settings, which is typically the dance and festival circuits,” he says.

“The current crisis in BC with illicit drugs is more often linked to injection/inhalation substances such as heroin and crystal meth, and what people would often call ‘street drugs’ instead of ‘club drugs’. And so, there’s very little knowledge of how to shift the drug checking technologies, but also drug-checking as a service, from club drugs to street drugs, because the services need to be responsive to the context and to peoples’ needs to be effective. It’s not just a medicalized service. And so we have proposals in right now to see if we can develop that, and develop it in a timely manner, knowing this is an emergency.”

While drug checking certainly plays a valuable role in harm reduction, Wallace calls for its integration within overall harm reduction schemes, saying on its own it is a limited service.

He also cites the main difficulty in implementing drug checking as a routine response to the opioid crisis: dealing with illicit substances. In order for a supervised consumption site, for example, to be legally allowed to check drugs, they have to first be exempt from the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act.

“I think that there’s still a lack of clarity in what can be done and can’t be done, and also how much that can really be facilitated, rather than a cumbersome process to go through,” says Wallace. “But how can we ensure that as a public health response, that the processes are facilitating increased drug checking and not limiting it, which I think isn’t really clear now.”

Wallace hopes that all three projects will be underway this winter.

“Harm reduction is about ‘staying safer when we don’t want to or can’t stop a behaviour.’”

Until then, both Wallace and Pal call for kindness.

”It’s not that we shouldn’t be doing the drugs, but we have to have a safety plan when doing it and that sucks,” says Pal. “But that’s where we’re at. And there should be no stigma around drug use, because everyone can drink as much coffee as they want in a day and it’s fine, but if I want to go and use whatever, that’s considered illegal because some government decided that it’s not something they could profit off yet.

“Harm reduction is about ‘staying safer when we don’t want to or can’t stop a behaviour.’”

Wallace and Pal both liken naloxone training and other forms of harm reduction (such as drug testing) to wearing a seatbelt.

“Seat belts are harm reduction. We use it every single day, but it’s not framed in that way. You know, traffic laws, crosswalks, bicycle helmets. All of these things are harm reduction because it is risky to drive a car, it’s risky to cross a road, but we don’t talk about it in these ways,” says Pal.

“It’s about compassion, it’s about meeting people where they’re at without judgement. It’s not about changing peoples’ views. It’s about keeping people safe and helping them make informed decisions that are right for them.”

Safe(r) partying and resources on campus

So where does this leave students who choose to use?

Campus Security all have to do naloxone training, says Swaich, and the UVSS and the University are currently discussing how to incorporate naloxone training into CL training. She is wary, however, of making this training mandatory for CLs.

“We don’t want to make anyone feel that they have to do something that they don’t feel safe doing, because again, that’s not something everyone would feel safe doing,” Swaich says. “I think that by offering the naloxone training and marketing it to CLs, those that feel comfortable doing it — which is probably a large number of them because those are already individuals that are taking steps to have these leadership roles — they’re probably more likely to actually want to receive the training. So I think that instead of making it mandatory, just having it offered is a good option.”

Materials distributed to students as part of the Safe Use campaign include information regarding the signs of an overdose and emergency phone numbers (including Campus Security, UVic Counselling Services, and UVic Health Services).

Swaich adds that within the next few weeks, the Safe Use campaign will be renamed to Safer Use.

“We don’t want to perpetuate that you can use drugs and be safe because that’s not real,” Swaich says. “It’s more that you can be safer. So we’re going to be updating our branding and calling the campaign Safer Use.”

For students looking to party without the risk of chance drug-encounters, the UVSS plans to hold monthly substance-free events as part of the campaign beginning in October. While details are yet to be finalized, Swaich says the events will be an alternative to drinking on a Friday night.

“We’re going to be trying to market that as an alternative to binge drinking for those on campus that don’t necessarily want to drink, because that is what so much of the culture on residence is right now,“ she says.

At the end of the day, telling people not to use illicit drugs oversimplifies the problems associated with the opioid crisis. It’s also not realistic.

“Often,” says Wallace, “drug use is not just criminalized, it’s stigmatized and people are penalized for drug use and isolated. And days like International Overdose Awareness Day help to humanize an issue that’s too often criminalized and stigmatized, and really show the support for people and to try to fight back against all the negative ways that people are referred to and treated and all the negative experiences.”