I have a confession to make: I wasn’t one of Brian Hendricks’ better students. I didn’t film the outside of his house in the dead of night and drop the film in the mailbox to get an A. In fact, I used to heckle him, and honestly, he gave as good as he got. I was that student for him. But, heckling aside, I was a follower.

It took maybe two or three rounds of his courses, but somewhere between the Writing 412 class about Stanley Kubrick and the one about the Coens’ (many writing students took it several times, including one speaker at Brian’s life celebration who said she took it 10 times—well after it counted for credit), I started to see what he was saying about “Golden Paths,” “Following One’s Bliss,” and all that other stuff he’d picked up with Joseph Campbell’s “Hero with a Thousand Faces” as a text/bible. My copy of Campbell’s book is often close, as is Tom Chetwynd’s “Dictionary of Symbols”; I have used them in film analysis and even with dream work throughout my journey since.

When I heard that he’d passed, I wasn’t devastated. He hadn’t adopted me as a surrogate father as he had done with my colleague, Brick Blair, or done me any other favours for that matter, but he had affected me greatly. Whenever I have flashes of deja vu in rather innocuous moments I feel his philosophy strongly. It’ll feel as though I’m “exactly where I’m supposed to be,” or on my own “golden path”. I had that feeling again about a month ago (the 19th of September to be exact) as I gathered with his family, friends and devotees at Lucky Bar for a celebration of his life.

It is hard, as I sit down to write out my experiences of Brian’s life celebration, to not pour a finger of fine scotch in honour of the self-proclaimed “Best Teacher in the World.” Of course he was joking when he said this in his final film collaboration, The Beauty of Certainty. That was Brian’s way; boastful and self-deprecating, honest and yet cunningly sly, brilliant and yet deeply shadowed; anima and animus, as he would fondly point out, at the same time.

The Beauty of Certainty, full of artsy endeavour, took up the first act of the proceedings. Self-disclosure, low angle shots and painful audio—courtesy of Brian himself—abounded. Brian put it together with my once-classmate Brick after his more serious diagnosis last year. To be honest, Times Colonist movie critic Michael D. Reid is far more forgiving in his review, particularly of Brian’s singing voice.

The Beauty of Certainty | Chapter One | But Now I See from Brick Blair on Vimeo.

Lucky Bar was auspicious for many as a screening room, it seemed, as that’s where Brian ended up hosting screenings of the student film night (I think 2002 was the last year we held it in David Strong’s lecture theatre) and it makes sense because honestly, a beer or two is required to get through all that angsty, artsy stuff. Lucky kindly hosted at the Hendricks family’s request, with Sandy, his wife of 33 years, wearing a veil to help those of us who didn’t know her to get it.

After saying hello to a few friends, I spoke with Nick Galichenko, the Russian Studies professor who would get Brian to fill in for him on the Russian film courses. Somehow Nick remembered me, vaguely, from when he spoke to the section of post-war Russian film (Russian 304, I think) I took with Brian in the summer of ‘98, right after Nick got back from Georgia (the country, not the state).

He spoke of being escorted in armoured vehicles and how, somewhere in there, he did something with a film festival. It was the reality of it that really highlighted the meaning of the films we had been watching, especially the ones about the continued militance and anxiety in the former Soviet states. Even today as we see these frustrations manifest on the world stage in the Ukraine, Nick and Brian’s course gave me a deeper sense of appreciation for a people’s revolution betrayed. Seeing Nick there, relaxing and sharing his time with all of us, showed me that Brian’s personality was one that broke barriers, especially in academia.

After the film, Brian’s son Dylan, his wife and baby son in tow, along with Kuba Oms (yes, the local singer sensation) , invited us all to share our remembrances of him.

I helped my friend Tim find his way to the mic, and was cast back into my own remembrances, helped by those who remembered him best: friends, family, near-family, golf buddies, and many, many students. At least 10 people spoke; some were long-winded and rambling, some teary, some short and to the point. Tim invited us to “pass the peace” and to “give a great big fucking hug” to whoever was next to us, because for many of us, it was church.

I nearly got a chance to speak. I was going to speak of teaching, of mentors, of educational scholar Ted Aoki, but I didn’t get the chance, so maybe here is the place.

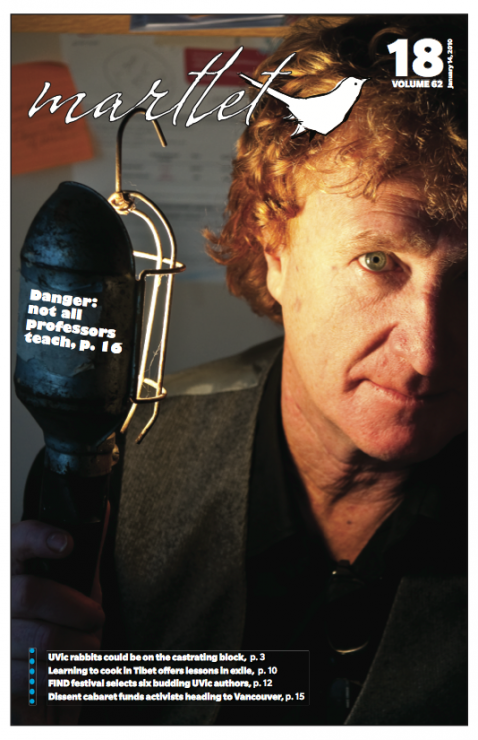

The “Dr.” thing stuck with me. I ran into him one week in 2009, the year Brian “retired”. He had confessed his early cancer diagnosis to a few at first, then to whole classes as I found out later, and was off to South America. When he told me, I think I smiled on the diagnosis as something “probably survivable” and wished him well in his new adventure. He was honoured with the front page of the Martlet in 2010 and I’ve asked that the current staff bring that article out for us to read, because it’s relevant. The teaser was, “Danger: Not all professors teach,” which is appropriate to what some said on the open mic. At that meeting with me, however, and later in the Martlet interview, he shared something that he couldn’t back when I wanted him to write letters recommending me for jobs in Japan or for Masters programs: he never got his MA, let alone PhD. He was just a sessional instructor. He was top tier at that point—he’d been a fixture since the mid ‘90s when I first started my BFA, and taught so many students that he might have been the most profitable sessional in the university, but he was still just a sessional.

Here is where his Rate My Professors rating and I strongly disagree. He was indisputably the most impressive sessional instructor UVic has ever seen, by far, hands down. To misquote Vincent Vega: I’ll take the Pepsi Challenge on that one any day of the week.

His classes were always full, and he taught like a machine. Where many professors had a hard time keeping up with research and committees and five classes a year, Brian would teach 10 or 12, often three or four classes a semester. I know: I took seven with him and they were almost always full. Not 30-people full, or 90-people full, but basically as-many-as-the-department-could-book-into-a-room-with-a-projector full. He wouldn’t kick out waitlisters, either; some classes students filled the aisles until someone would get a whiff of his crazy and drop.

[pullquote]Brian was a being brave enough to stand in a university and be himself: a consummate connoisseur of film, a father, and even a failed writer…By modelling that first, he did for many what they could not do for themselves. He gave them a reason to bleed on the page.[/pullquote]

The amazing part was that it wasn’t just Brian’s movie picks that everyone came to see, although that was certainly part of it (I mean, who doesn’t want to watch The Big Lebowski for credit?). But rather, as I heard again and again at the open mic, it was Brian: his thematic analysis, his take, his readings of other student’s work, his performance art as teaching, his humanity—that’s what they really stayed for.

I have heard differing opinions from some still in the department hazarding that others taught WRIT 412—his course, as he called it—better than he did. I will contend that while they may have taught it better, he was it better. Brian predates Rate My Professors, but had it been up in his heyday rather than the sunset of his career, someone would have found a way to hack it and give him a score over 5.

One such colleague, Jeremy Lutter, director of short films “Joanna Makes a Friend” and “Floodplain,” sadly missed the celebration. His shorts have taken him to Cannes twice now, rubbing elbows with Cronenberg and the other Canadian film contingent. He was asking on Facebook for a good roof to shoot on for an upcoming project called “Caw”, and I suggested the roof of the Elliott building (of happy-face fame), as I filmed there back in 2002. I sent a link to my WRIT 320 project wherein I hokily kissed my not-yet-wife out behind the HVAC pipes, after being scolded by Brian in a classroom and finding my way out of the labyrinth of the school. His one word reply said it all: Hendricks!

As the evening was invaded by millenials, as the bar went back to being a bar, another round of “Amazing Grace” was struck up, probably so we could join in and find key better than Brian did in his farewell film, and I found myself amongst his family, next to Kuba, harmonizing in bass to his tenor, celebrating a light we could all blindly see.

To quote noted scholar Ted Aoki, who mused on the death of teacher Christa McAuliffe in the 1986 Challenger disaster in his seminal Curriculum in a New Key,

“She is the teaching… [Her] absence speaks to me with a strong presence of what her teaching essentially was and is.”

For many, especially those who couldn’t believe that Brian was the great teacher that so many claimed because he wasn’t a noted, peer-reviewed scholar or professor — to them he was ‘just’ an awesome uncle, or great golfing partner and a very dear human being — he, like McAuliffe, was the teaching. Brian was a being brave enough to stand in a university and be himself: a consummate connoisseur of film, a father, and even a failed writer. He laid his foibles bare, and shared generously of himself with others. By doing this he implicitly invited others to share to do the same as honestly as they could. By modelling that first, he did for many what they could not do for themselves. He gave them a reason to bleed on the page. Many sat at the back with their arms crossed, but given an opportunity to set cynicism aside and be honest, some came around, opened up, and made good art. Keep an eye out for them—the cult of Hendricks. All out there following their bliss.