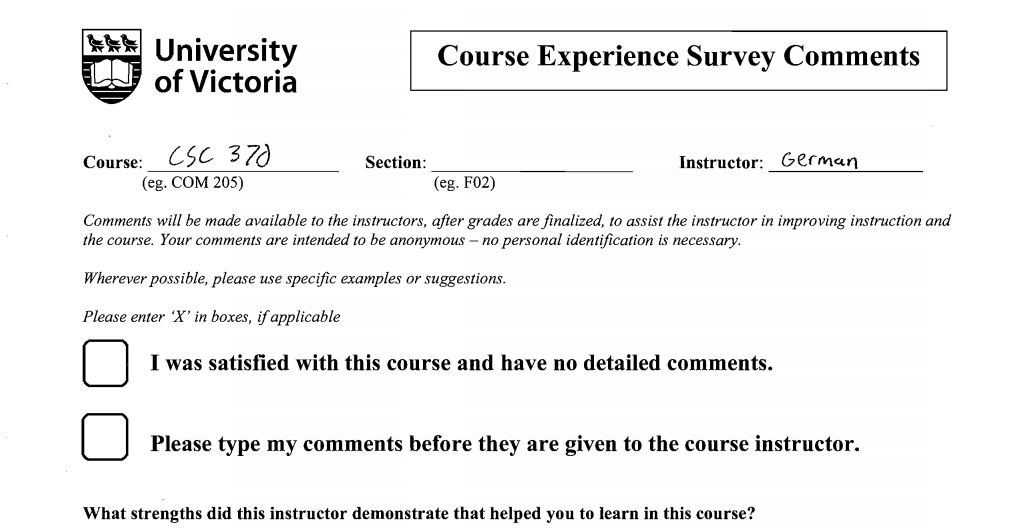

This evaluation, from Daniel German’s CSC 370 class in the fall of 2010, offered students the option to have their comments typed up. –Provided (screenshot)

Over the summer term of 2014, UVic transitioned their end-of-term Course Experience Surveys (CES) from a handwritten form to an online survey that has been in use since. The survey, created by Montreal-based eXplorance Inc., guarantees confidentiality; however, the online surveys now require the user to provide their NetLink ID before responding, whereas the paper surveys did not require that information.

Teresa Dawson, the director of the Learning and Teaching Centre, insists that student identities are kept confidential. “There is no time in which your individual responses are kept as individual responses,” said Dawson. “They go straight into that secure database separated from anything that has to do with your identity.”

However, Dr. Daniel German from the Department of Computer Science, who teaches CS360: Security Engineering, referred to the system as providing “partial anonymity,” as, theoretically, system administrators could have access to the files, data, and their authors. Those who do, however, are entrusted with keeping that information confidential.

[pullquote]“There were some differences across the campus,” said Dawson. “Whether they were typed or not, how many students it would be before they were typed . . . It varied. In some cases the department kept the copies and gave the [professors] the originals, and in other cases, it was the other way around.”[/pullquote]

German’s interest in the system began when the partial anonymity of the new system alerted the Department of Computer Science to a glitch in the surveys, allowing students who had dropped a course to still fill out a CES. “This was fixed by knowing who [the sudents] were,” German said. The system now also records whether surveys have been completed or not in order to prevent students from submitting multiple course evaluations.

On Learning and Teaching Centre’s CES FAQ website, it states that, “A small number of Systems administrators do theoretically have the ability to access individual student surveys. However this is strictly forbidden, just as it is forbidden for them to view any confidential information with which they are entrusted . . . These employees sign a confidentiality agreement with the university before being hired.”

“This is kind of minor within the scope of the important things that we have to worry [about],” said German. “But, I think it’s still backwards. From the almost ideal, practical anonymity, to now a system where anonymity is preserved by the administrators.”

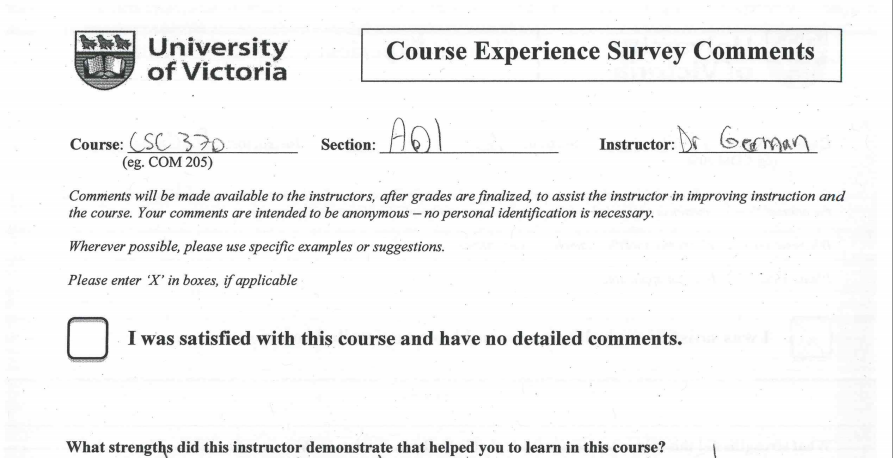

While the new electronic system does require a NetLink ID, Dawson says the previous system was not ideal as procedures thought to be university-wide were not uniformly implemented. For instance, German received photocopies of handwritten responses from computer science students. In some cases, students could request UVic staff to type their comments in case their handwriting could be identified, but in examples provided by German, that checkbox was not offered on his Spring 2012 CES while it was in Fall 2010.

“There were some differences across the campus,” said Dawson. “Whether they were typed or not, how many students it would be before they were typed . . . It varied. In some cases the department kept the copies and gave the [professors] the originals, and in other cases, it was the other way around.”

Dawson further explained that the old system was set up to be temporary and could no longer handle the growing number of submissions. [The old system] couldn’t cope,” she said. “It was 100 000 forms going through one old scanner. Plus, there was a sense that we couldn’t assess anything else there. People might want to have feedback for other people, or they might want to use the systems for other things but we couldn’t ,because we couldn’t even cope with the volume that we had.”

The “old” system only began in 2002 when the UVic Senate passed a motion to support the development of a standardized university-wide course survey. This was later called the Course Experience Survey, or CES, and was not piloted on campus until the spring of 2009. This system was powered by a combined effort of the Learning and Teaching Centre, University Systems, and the Office of Institutional Planning and Analysis. As this labour intensive and multi-office system was meant to be temporary, once a proposal for online surveys was sent to the Senate in the spring of 2013, it was implemented just a year later in the summer of 2014.

This survey, from the same course in spring of 2012, did not offer the option for comments to be typed. –Provided (screenshot)

Commenting on the level of anonymity in the old system, German said, “Before, you could [be identified], but there was always the potential of deniability,” meaning that professors would be hard-pressed to clearly link handwriting style to a particular student. Using the example of a computer voting system, German points out that even if you are told that a computer system is secure and anonymous, there is no way to prove that statement. “Security is not binary. It’s more like a spectrum,” he said. “With enough effort, there is probably no system in the world that will be truly secure.”

In extreme cases, because the current CESs are still theoretically traceable, UVic Faculty of Law civil procedures professor, Andrew Pirie, believes that there is a possibility for information in CESs to be disclosed for a court of law.

“The answer would depend on the type of legal issue,” he said via email. “But if a student evaluation was relevant to a legal matter before the courts I am quite certain the evaluation or evaluations would not be privileged—that is not subject to disclosure.” In a scenario Pirie described as “remote,” anonymity would be broken if there was believed to be information relevant to the courts in the evaluation.

Despite the partial anonymity, Dawson explained the importance of the new system in its inclusive value saying, “Students have written to me and said, ‘I have a learning disability and I have never felt comfortable writing before because I had to write by hand. Now, I can spell check, I can take my time, the extra time I need, so I really feel my voice is being heard.’ The same thing with students who have English as a second language.”

Historically, schools that have transitioned from hand-written to online forms see a drop in the numberof students who are completing the forms—which could potentially lead to a skewed result. After making the transition in 2012, McGill University saw their response rate drop to 42 per cent and only reach a normal rate of 50 to 51 per cent after several years.

German, for instance, said that because class time was no longer allotted to filling out surveys, he saw the response rate of his students drop. “In the first section I was teaching,” he said, “the numbers varied from 20 to 45 per cent of students filling in [the response].”

German says that if students are not made to fill out the responses immediately, they will not do so in the three-week period provided. Dawson similarly attributes this to the loss of available class time to do the surveys. “Generally response rates go down first and then they tend to recover,” she said, “as long as the institution communicates well around it.”

“I think the only thing that could be lost [with electronic surveys] is if we don’t pay as much attention to [them],” said Dawson. “You want to do it in class because you want to keep signalling that this is an important part of citizenship as a student, and it’s an important part of learning and it makes the course better for other people down the line. If we push it back on to student time outside of class, then in my mind it’s not as much of a focus. That, I think, would be a shame.”

On a societal level, German believes it is important for the public to be aware of the relationship between technology and privacy.

“Perhaps nothing will happen here at UVic with respect to changing the system, but I think it’s important to think of the repercussions of going into an electronic life and how it will impact a right we had until now, which is a right to anonymity. It’s not enshrined as a right, but it’s derived from the right to privacy.”