A student in UVic’s business school says the program’s progressive slant means his conservative ideas are either disregarded or ignored.

Will Goldbeck, a fourth-year student at UVic’s Gustavson School of Business, says neither the courses, his professors, nor the school itself do a good enough job of allowing debate for key business theories.

Instead, Goldbeck says courses skip past sections of textbooks that offer critical perspectives of progressive concepts that are taught and professors shrug him off when he attempts to bring up differing viewpoints in class.

Goldbeck’s concern centers mainly around a business theory called Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), a theory that business shouldn’t focus exclusively on profit — they must also be conscious of their workers, their consumers, the environment, etc.

CSR is a relatively recent concept in business, whereas Goldbeck’s profit-first thinking is more in line with business beliefs of the 70s.

Milton Friedman, a renowned American economist, is often cited as the leading critic of CSR. An essay from Friedman was present in a chapter of Goldbeck’s textbook for his Business Ethics class, but according to Goldbeck the professor didn’t discuss the essay when teaching the chapter.

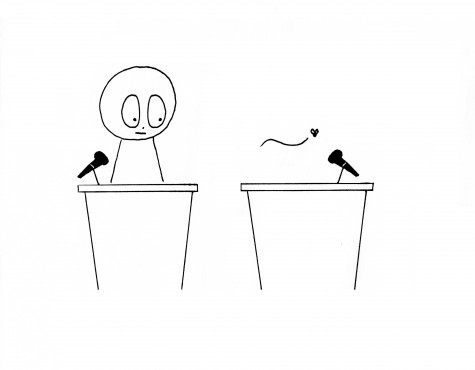

“I put up my hand and said, ‘hold on a second, what about this guy’s look at CSR?’” says Goldbeck.“[My professor] said that opinion’s not valid, he didn’t say why, and he said ‘we’re moving on.’”

Ellen Dewar, a business student and president of the Commerce Students’ Society, acknowledges that UVic’s acceptance of CSR theory is not surprising.

“We’re one of the only business schools with a mandatory sustainability course, and that’s because one of the pillars of the Business School is sustainability,” Dewar says. “So it’s obviously pretty integral to the Business School and how they want their students to think about things and encourage a new generation of businesspeople who are more [socially] responsible.”

But Goldbeck says the program refuses to even acknowledge an alternative to the theory.

“I think it shows that they have a certain niche in the Business School community where they’re going to be over here on the left, and they’re going to have this political bent in with their teachings, and they really couldn’t care less if you disagree with them,” Goldbeck says. “That’s their brand.”

In a statement responding to Goldbeck’s concerns, the university argued their teachings are based on tried and tested business methodology rather than political leanings.

“Ultimately, the faculty is responsible for curating the course content based on their expertise, the mission of the school, and current business research. Student discussion and questions are always welcome, but opinions expressed in an academic setting should be substantiated by credible source material or personal experience in business,” the statement reads. “While students are entitled to their views, the position on corporate social responsibility espoused by the business and sustainability faculty is supported by currently accepted business research and best practice.”

Dewar says Goldbeck’s ideas are controversial — something Goldbeck acknowledges as well — but she doesn’t think he is alone in his beliefs.

“I don’t think he’s the only person,” Dewar says. “I know for a fact there’s a handful of other people, but they’re usually not vocal about it in class because they know it’s an unpopular opinion and they usually kind of stick to themselves.”

Their silence, Goldbeck says, is as harmful for those who agree with the concepts of CSR as it is for those who don’t.

“If I was a proponent of CSR, I would want as many people to disagree with me as possible at school because that’s how you really sharpen your ideas,” Goldbeck says. “I think that’s how arguments get better . . . you listen to the other side and you correct or you improve.”