A repetitive yet refreshing take on maternal grief, menopausal dysphoria, and female impotence

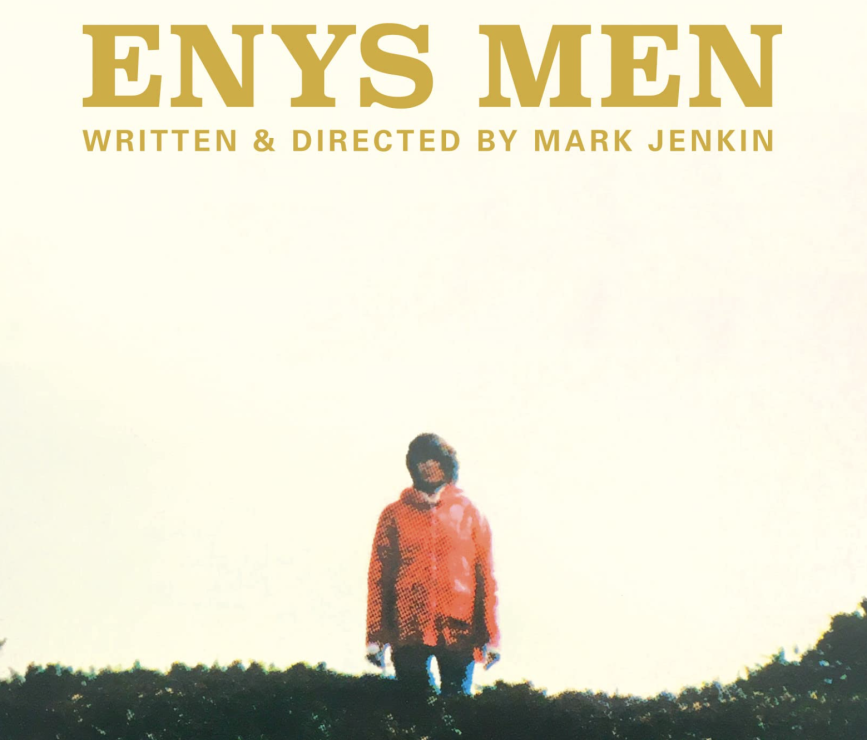

Promo image via IMDb.

Cornish filmmaker Mark Jenkin makes surrealism out of minimalism in his latest cult horror exercise, Enys Men. The title, translated as “stone island,” means a lone skerry with only a single cottage to house its soul inhabitant.

Mary Woodvine plays the film’s unnamed lead. A wildlife volunteer who, in 1973, has been stationed on the remote isle to study a single patch of flowers. Save her transistor radio, almost all of her amenities are dependent on the petrol delivered in a scheduled supply drop. One day, however, the supply vessel doesn’t come. Ominous visions begin out of the corners of her eyes and the island’s soundscape becomes more disquieting by the minute. Yet, Jenkin subverts this increasing terror by having his subject remain unphased, no matter how uncanny her situation becomes. This could hint at the narrative actually being a series of the volunteer’s memories, dreams, or a collage of both. Regardless, the confusion of Enys Men’s esoteric atmosphere is clearly intended for its audience rather than its heroine.

As her routine goes from habitual to compulsory, each of her visions become more spectral and amnesiatic than the last. Virtually every prop, location, and eerie sonic cue is reincorporated with each day spent on the island. The film allows us to feel some of the volunteer’s daily monotony while somehow avoiding her boredom.

Themes of maternal grief, menopausal dysphoria, and female impotence recur throughout. This alludes to a potential link between the events on-screen and a psychological break stemming from mid-life upheaval. While there is certainly a mystery to be decoded within Enys Men, it never serves a climax or twist, instead acting as a vehicle for the film’s own frightful rhythm.

Jenkin’s method relies on retro-cinematic techniques. His choice to shoot on 16 mm creates colour saturation reminiscent of 70’s cult cinema. Enys Men was also filmed within three weeks during the COVID-19 pandemic. Production wrapped with a minute carbon footprint of less than 0.15 per cent of the CO2 a typical production produces. These facts, in addition to the film’s bilingual releases and positive box office returns, point to ethically conscious filmmaking being both sustainable and profitable. Few films are as simultaneously repetitive and refreshing as Enys Men.

While it’s not a film for all, clearly there is an audience willing to watch Jenkin melt time and bend reality in Cornwall’s most isolated corners. Find out if you belong to this minority when the film is released in North America on April 18.