Remembering the Holodomor, remembering our voices

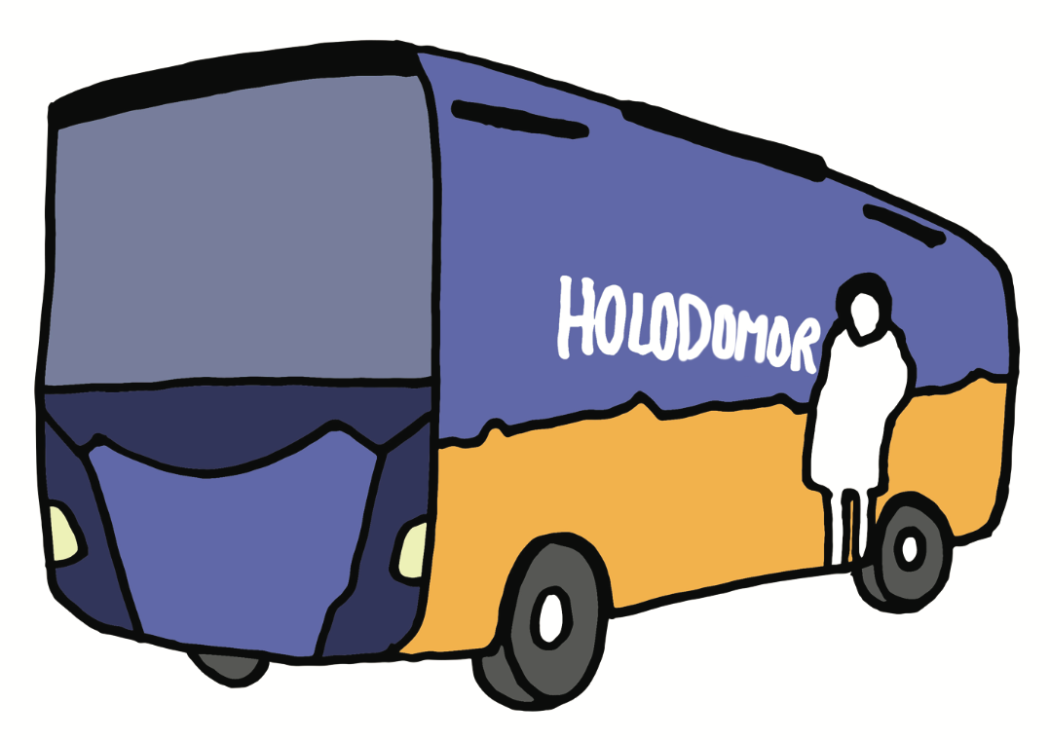

The bus is impossible to miss. It’s massive, painted with orange wheat fields, blue sky, and “HOLODOMOR — THE UKRAINIAN GENOCIDE” in white capital letters. A sight that causes drivers to do double takes on the highway, it was equally arresting parked outside UVic’s McPherson Library.

This is the Holodomor National Awareness Tour bus. For the past three years it has visited schools and communities across Canada to raise awareness about a genocide that the world has largely ignored — Stalin’s starvation of Ukrainians in the 1930s.

Inside the bus is seating for 33 people and a 24-foot-long video wall. Screenings depict survivors relaying their stories of scavenging horse meat, of being given up to orphanages by parents who couldn’t feed them, of looking at the mounds of grain awaiting export, and of guards stationed in watchtowers to shoot anyone taking even a handful of grain from the fields.

The Holodomor was covered up until the fall of the USSR, when archives were made publicly available. Even now, only 17 countries recognize the genocidal intent of the man-made famine. Russia is not one of them.

The Holodomor National Awareness Tour hopes to combat this selective historical memory by providing awareness and knowledge to educate about the atrocity.

But the tour does much more than teach about an Eastern European tragedy that, to Canadians, may seem far removed from our lives.

By using the Holodomor “as a lens,” the project teaches about the “courage to speak up about truth, about tolerance, civility, and democratic values.”

By using the Holodomor “as a lens,” the project teaches about the “courage to speak up about truth, about tolerance, civility, and democratic values,” says Roma Dzerowicz, Executive Director of the tour.

It does this through the use of international award-winning technology to engage students. When the bus visits grade schools, entire classes take part in interactive lessons that utilize individual iPads to answer questions and build murals on the screen.

And, according to Dzerowicz, the kids love it.

“It’s amazing how students realize that … we have a voice. We can create a statement, and we can create knowledge,” she says.

The mobile theatre-and-classroom is so successful that the bus is always booked solid. Based in Toronto, the project has trouble even meeting the demand just from schools in Ontario. Many schools want the bus back every year.

Dzerowicz is “impressed and overwhelmed” by the tour’s reception – and she is already planning another lesson for grade school students.

“There is much more to come, and I’m really excited about it,” she says. “[The project will] continue on for as long as it possibly can, until the bus breaks down and money is found to buy a new bus. We have all the technology, we know how to put it together, we know what works.”

Ideally, Dzerowicz would like to see other mobile classrooms raising awareness about atrocities and using them as frameworks to teach Canadians about human rights and democratic values. But for now, the Holodomor National Awareness Tour bus will keep rolling on.