Now, the thriving Victoria climbing scene offers a similar promise

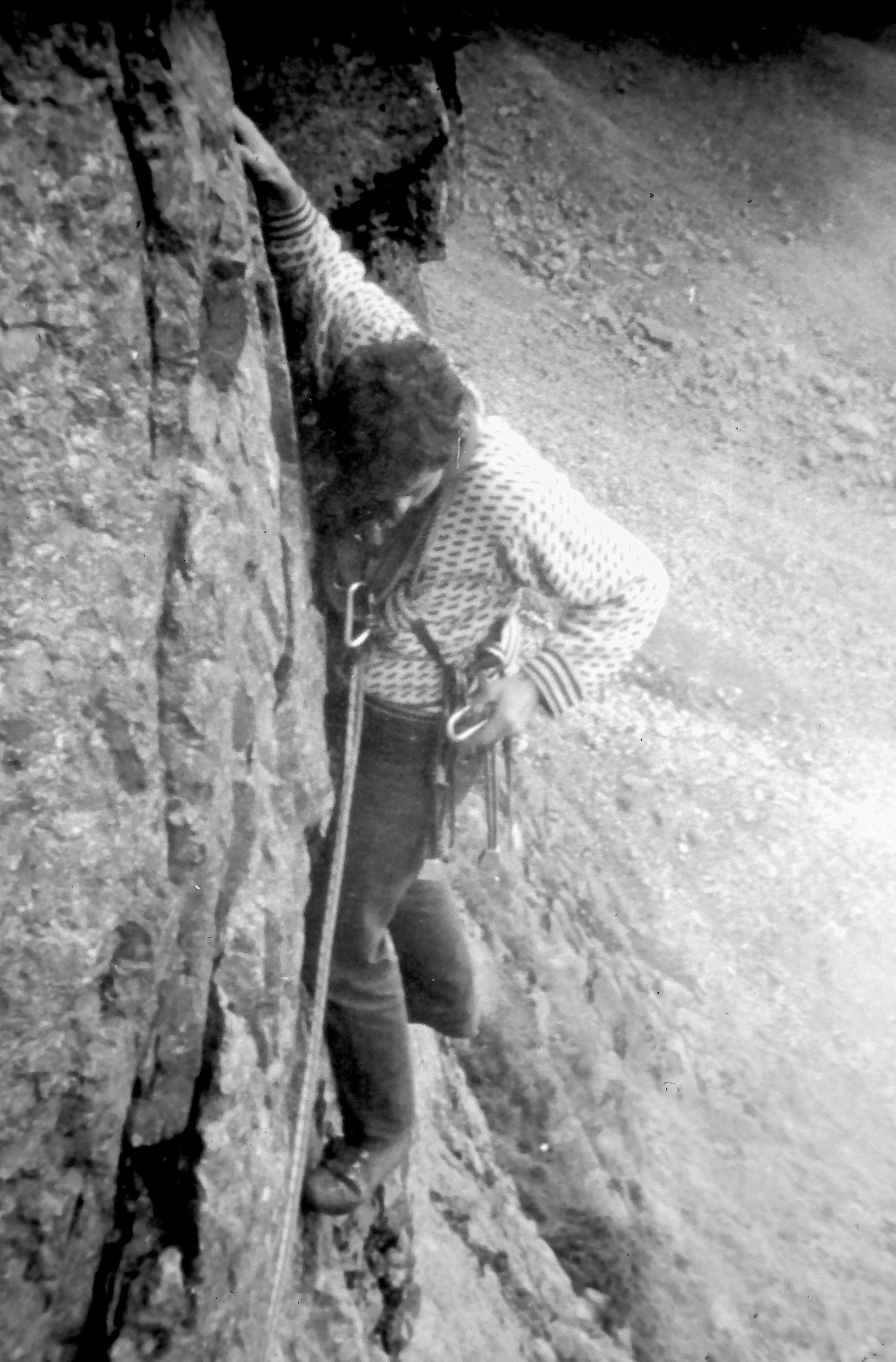

Photo courtesy of Howie Richardson.

It’s a Thursday evening at CragX climbing gym in Victoria, B.C. Located on one of the busiest streets in the downtown core, the gym’s floor to ceiling windows and colour-marked walls cut a dramatic figure in the dusk.

Photo by Silva Erglis.

Almost every rope is occupied. Legions of climbers wait patiently for their turn on the lines while others sit, chat, and chalk up before trying their hand at the newest bouldering route. It’s a perfect glimpse into the Victoria climbing scene — a network that seems to never stop growing, and one I’ve been a part of for the last year, though it already seems like a lifetime.

My first experience climbing in Victoria was an introductory lesson at the CARSA Climbing Centre at UVic. There’s a small library tucked away to one side of the space with no more than fifteen or so books. One in particular grabbed my attention: Skaha Rock Climbs, a 250-page paperback guidebook authored by Howie Richardson. The cover features a lone man, sunglasses on, hat worn backwards, calmly clinging to the side of a rugged crag.

Richardson, now 80 years old, has spent more than half a century climbing and mountaineering. His journey started in Bristol, England, at a time when climbing was an unconventional sport.

“There weren’t many people climbing then,” Richardson tells me over Zoom, his gravelly voice crackling through my speakers. “I only knew one other climber, and I asked him if he ever took people out, and he said, ‘No.’”

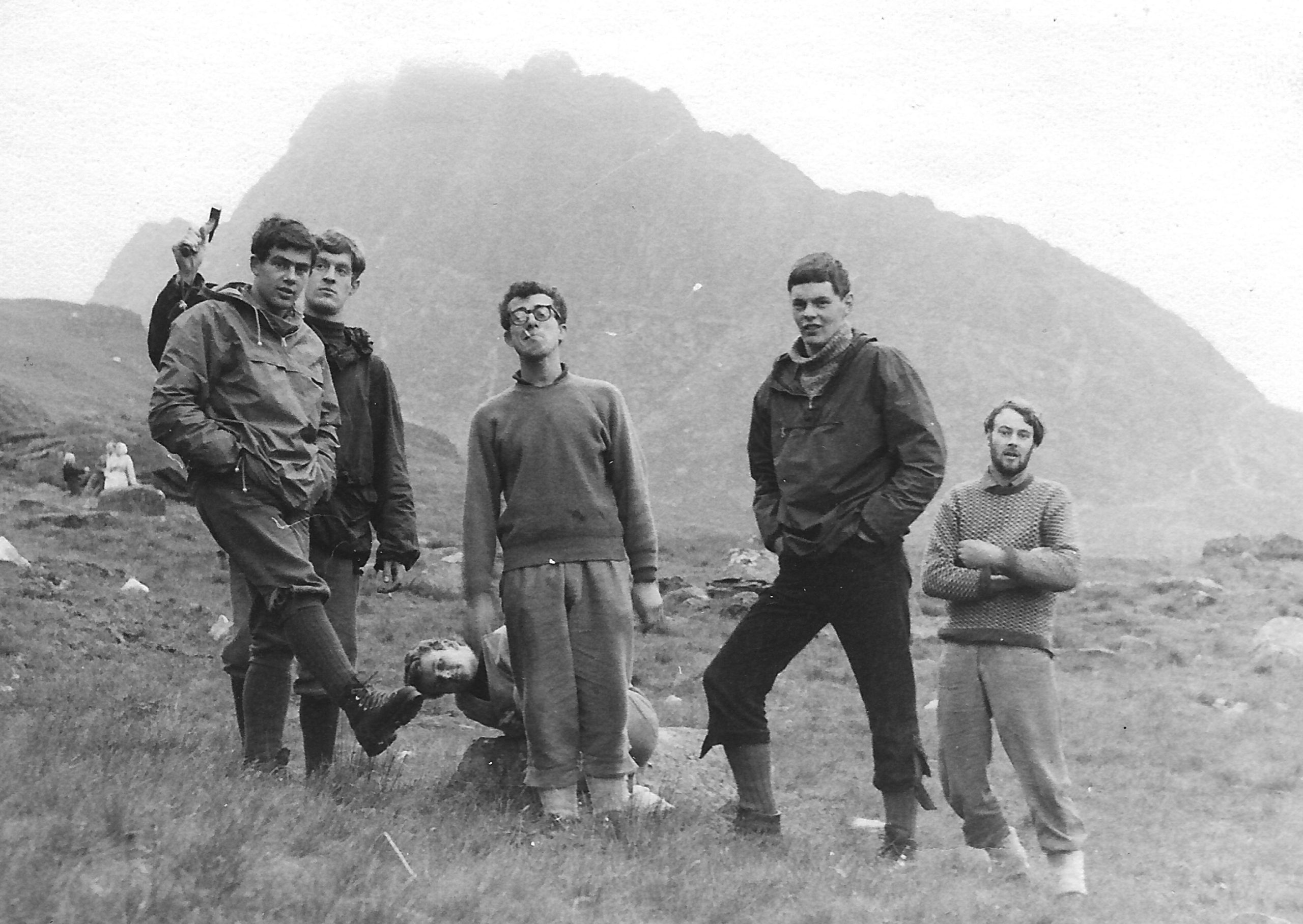

Photo courtesy of Howie Richardson.

Despite that initial setback, Richardson persevered. He found ways to immerse himself in the sport, first through the Loughborough University climbing club, and eventually through his almost twenty-year career as an Outward Bound instructor. Before long, he was travelling the globe and climbing in some of the most iconic and remote regions on earth — the Himalayas, Patagonia, and the Swiss Alps.

However, Richardson is best known for his establishment of Skaha Bluffs, an outdoor recreation capital in British Columbia’s Okanagan Valley that consistently ranks as one of the top climbing locales in Canada, and where Richardson recorded the first ever climb in 1987.

“I started purely selfishly,” says Richardson. “I was just looking for a place where I could go climbing.”

Richardson consistently dodges attempts to label him a trailblazer or a pioneer. But when the Bluffs first started to grow in popularity, Richardson was the central cog of the entire machine. He opened up his home to climbers from around B.C., who camped on his lawn before setting out to climb routes that he discovered and set.

He was also the first chairman of the Skaha Climbers Association, and when local hunting guides attempted to remove climbers from the area, he helped secure a deal with Mountain Equipment Co-O (now Mountain Equipment Company), who pitched in the first funds to buy access to the Crown land the Bluffs stand on. Despite this, Richardson is reluctant to acknowledge the enormity of his influence.

“My biggest contribution, probably, was parking,” he says, matter-of-factly, of his hand in establishing the Skaha Bluffs car park in 2007.

Photo courtesy of Howie Richardson.

Whereas Richardson has spent much of his life as a loyal Okanagan Valley climber, many Victoria natives feel similar pulls to their city as a thriving hub for the sport. Why do certain places emerge as nerve centres for climbing and mountaineering? Is it solely geography?

The appeal of climbing towns like Squamish, dominated by granite cliffs on every side, and Canmore, nestled among limestone bluffs and Rocky Mountain glaciers, is no mystery. These places boast world-class natural features that inherently draw in outdoor enthusiasts. But Victoria presents a more complex case. Why has it become so synonymous with climbing, despite lacking the dramatic and numerous outdoor routes that define other Canadian climbing epicentres?

For Richardson, it all comes down to the people — the cities and the community feeding into one another.

“It’s positive reinforcement in lots of ways,” he says. “Climbers are just amazing … they’re smart, entertaining, interesting people, and to not want to bring those people into your community would be kind of foolish to me.”

Climbing, at its core, necessitates collaboration. At least for beginners, the sport makes you inherently dependent on others. You cannot belay yourself. You need someone to anchor you, someone to guide you. At any given moment on the rock, you are quite literally putting your life into someone else’s hands, and when you trade roles, they are entrusting you with theirs.

It isn’t just an exercise in teamwork — it’s a shared responsibility that cuts deeper than the sport itself. The bond between climber and belayer transcends skill level, background, or personal differences. It’s a sport that requires community, even when it’s difficult, and fosters a culture of inclusivity that is rare in competitive sports.

Brandon Lowe and Jamie Borthwick, co-presidents of the UVic Climbing Club, echo this sentiment.

“I started climbing over at CragX, and I felt welcomed,” Lowe explains. “No one was judging me. Everyone was just kind of there to help.”

Both Lowe and Borthwick found climbing recently, after practising other high level competitive sports for most of their lives, and were struck immediately by the collectivism that makes climbing unique. When considering his favourite climbing moment, Lowe recounts the day that he surpassed the friend who first introduced him to the sport.

Photo courtesy of Howie Richardson.

“I just felt that sense of accomplishment,” he remembers. “And for once in a sport, he wasn’t upset. He was proud, and it just felt really good, and really kept me on it.”

In a university town like Victoria, the culture of climbing seems to resonate particularly well with students. It makes sense. Many of us have left our homes for the first time. We’re entering new, often intimidating environments. The fear of not fitting in or not making friends is palpable. And in a world that can often feel fragmented, isolated, or downright lonely, climbing can offer a reprieve from all that chaos. When you’re on the rock, the only thing that matters is the climb, the rope, the next move you’re planning to make.

“It’s a stress relief for me,” says CragX member Grace Decker. “You can just focus on the wall and nothing else … and I think that was what compelled me to keep doing it.”

For some climbers, like Khaled Homsi, who first immigrated to Montreal from Malaysia seven years ago, climbing offered a way to feel at home in a new environment.

“I’ve been climbing since I came to Canada,” Homsi says. “I like it because it’s made me make friends in the country, in the industry, in a new city … and it’s the first way I started finding jobs as well.”

As the current community manager at CragX, Homsi knows better than most how important it is to foster this environment of acceptance.

Photo by Eric Kwakernaak.

“Our gym is more climbing community oriented,” Homsi explains. “Because, in the end, climbing is two people. You need to build this trust into the community.”

And it’s obvious that CragX’s approach has been working. On their chalkboard, there’s a large space where anyone can write their name and a description of themselves, so that other solo climbers can find them and get together.

The chalkboard is practically full, and as I look around the gym, I see nothing but groups, working together to solve the puzzles of the walls. Individuals have been absorbed, something that climber Brett Gibb cites as one of his favourite aspects of the sport.

“I never feel like I am climbing alone,” says Gibb as he belays. “The community of climbers … they’re all very inclusive.”

While climbers like Decker, Homsi, and Gibb highlight the sense of belonging inherent in the sport, Richardson’s stories remind me not to get too sentimental. Climbing is not without its risks, and Richardson has had his fair share of near misses and close calls — perhaps an unavoidable aspect of a life dedicated to a sport that puts so much on the line.

Photo courtesy of Howie Richardson.

“When I was at college, I fell about 60 feet … a couple of times,” Richardson tells me. “Each time, I hit the ground just as the rope caught me on a piece of manky gear that was placed in a crack … I was either going to die or I was going to be okay, and when I hit the ground, I realized I was okay.”

Richardson’s stories are those of a man who has lived three or four lives. He once hitchhiked from England to Kolkata on his way to Hong Kong, where he had been offered a job — a trek over 8 000 km long. He recounts the four years he spent researching Northwestern Crows on Mitlenatch Island for his PhD — entire summers on an islet less than half the size of UVic’s campus, equipped with nothing but a small wood cabin and no radio. Or once, being caught in a midnight avalanche in Patagonia with ice blocks the size of refrigerators raining down on him and his ice axes piercing into his side.

“Nobody knew where Patagonia was in those days … we were hundreds of miles from any help with no phone or anything,” Richardson says. “So that was a bit grim.”

Richardson leaves me feeling like I should burn my laptop and replace it with a compass and a paper map. He makes me want to sell my TV and use the money to buy a good travelling pack. When he speaks, it is as if adventure is calling through the screen.

While Richardson is a climbing pioneer, he is by no means the only one. If you look back far enough, you can find individuals like him in almost every major climbing hub in B.C.

Photo courtesy of Howie Richardson.

In Victoria, it was people like the legendary Jim Sandford, one of Canada’s most celebrated climbers, who grew up in Victoria and started bouldering at Fleming Beach. Climbers like Greg Foweraker, Peter Croft, and Hamish Fraser also frequented climbing spots in Victoria, and it was that same crew who would eventually help grow the climbing scene in Squamish in the late 1970s. But they never forgot their Island roots. And, like Richardson, they never stopped looking at climbing as a way to connect with others.

“I was essentially a college boy from Victoria who would parachute in for short intense periods of climbing,” Foweraker, a UVic alum, once said in an interview with Gripped magazine. “My best memories are the sense of mental and physical creativity, with the enormous level of fun that climbing gave us.”

Reflecting on my conversation with Richardson and the stories of climbers like Sandford and Foweraker, I am struck by the quiet power of those who build communities. They do not seek credit, yet their contributions shape the very fabric of the sport that so many of us have the privilege to enjoy. When new climbers hear about Richardson’s story, they are inspired to follow in his footsteps.

“I definitely want to stick with it, as long as my body allows me to,” says Jamie Borthwick, speaking amidst a busy crowd of other students. “And when my body doesn’t allow me to anymore, I will come support the climbing community like the mom that brings orange slices to soccer practice. I will be there.”

Photo courtesy of Howie Richardson.

As the B.C. climbing scene continues to grow, it’s important to remember the pioneers who laid its foundations. People like Sandford, Foweraker, and Richardson didn’t just open up new routes — they created spaces where people could come together, share experiences, and build structures that would endure long after they stopped climbing. And they were, in turn, gifted with memories that have lasted them a lifetime.

“Standing on the top of Mount Sir Donald with my sons, Robin and Tony, after we soloed up the classic southeast ridge” is Richardson’s favourite climbing memory. “Just an awesome day, starting at dawn, and we just moved up there so, so easily, so steadily…. If there were other ones, they would all involve my family.”

Reflecting on the ways that climbing has impacted him, Richardson pauses for some time. His eventual answer is measured.

“Climbing changed my life,” he says, “because it took me to places that I would never have gone before.”

Sport is unique in that way. It can shape lives and rewrite histories. In Richardson’s case, it brought him to breathtaking pinnacles and remote places, but more importantly, it built a life of connection. First with the legion of climbers that slept outside his front door in the early days of the Bluffs, then with his family, and now with the countless newcomers who hope to follow in his footsteps — myself included.

Richardson reminds us that it isn’t just about the summits we reach; it’s about the people we trust to hold the rope, the friends who cheer us on, and the communities we build, one handhold at a time.