Get to know more about the Climate Disaster Project through its director

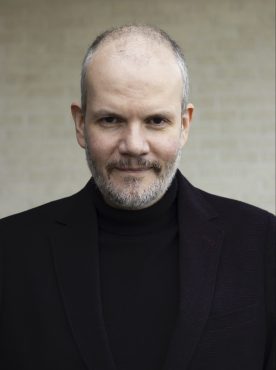

Photo provided by Sean Holman.

Sean Holman has been teaching trauma-informed climate journalism at UVic since last year, and is the head of an international project that gives a voice to survivors of climate disasters.

I sat down with Sean to learn more about who he is, what his position is here at UVic, and the work that he is doing.

Tell me a bit about yourself.

My name is Sean Holman. I’m the Wayne Crookes Professor of Environmental and Climate Journalism, and Director of the Climate Disaster Project.

The first part of my career was spent as an investigative journalist. I covered provincial politics for 10 years, mostly reporting on natural resource development, child welfare, and political corruption issues.

During that time, my reporting resulted in the resignations or firings of at least eight different party or public officials, as well as changes in law and policy.

I then cashed my chips in and got a job in academia as a journalism professor at Mount Royal University, where I became really interested in the history of freedom of information, which led me to become interested in why we value information in democracies. That interest really led to a concern about how the news media was reporting on climate change, or often not reporting on climate change, and what we were doing and not doing with that information.

What is the Wayne Crookes professorship?

So basically, my job is to take action in the best way I know how, on the most pressing issue of our time, and involve students in that process.

I’m director of the Climate Disaster Project, which is a collaboration with 12 other post-secondary institutions. Students work with climate disaster survivors to share their stories and then investigate common problems and common solutions that those survivors have identified.

The idea behind the project is that we are all climate disaster survivors in one way, shape, or form, but we do not think of ourselves that way. Climate change has often been presented as a large-scale environmental problem, as opposed to one that is human-scale in the here and now.

In failing to appreciate that we are all climate disaster survivors, we often feel alone in our experiences with climate change. By sharing the stories of how we have been impacted by climate change in both small and large ways, we can create community around that experience. And if we can create community around that experience, then we can find hope.

When did you first become interested in environmentalism?

I’ve always been. I reported on resource development issues when I was an investigative journalist because I care about the environment. But for me, I became concerned about the environment and concerned about climate change — and how the news media was covering climate change — probably in 2017, and this is when the wildfires in B.C. were billowing smoke over the Rockies.

The news media was failing to routinely provide the public with information about why this was happening. They were routinely failing to make the climate connection. If the media fails to make that climate connection, how can we expect people in their lives as consumers and voters to make good decisions about safeguarding our planet?

That was what resulted in me writing a widely-shared open letter calling on the news media to cover climate change with the urgency that it demands.

Anything you want to say to UVic students?

Sign up for Writing 344 and 345. These are courses that allow students to directly take action on climate change as part of their coursework. You’ll get a chance to work with people and communities who have been acutely affected by climate disaster, share their stories publicly via our news media partners, and then help empower those people and communities by taking their concerns seriously.

There are so many reasons to feel despair right now. But what I know is that the students who have participated in this project [say] that it’s been a transformational experience for them, because it positions climate change as not this scary thing that’s happening in the future that we can do nothing about, but this scary thing that’s happening in the present. We can do something about it, and it doesn’t help to ignore it.

I think part of the problem with the climate movement in general is that it is a movement entirely based on anxiety. I don’t know any successful social movement that has ever been based on anxiety, so let’s try something different.

This interview was edited for brevity.