Exploring nudity and sexuality under the shadow of the algorithm

When Rita Bunrayong put her newly completed photo series, “Suffocation,” on her art Instagram account, her work got censored.

The offending photos — a collection of nude self-portraits — depict Bunrayong in a bathtub, and are another casualty of Instagram’s increasingly stringent restrictions on what they deem as unwanted nude or sexual content.

When Bunrayong tried to send the screenshot of the removal to the Martlet on Instagram, she instantly received another threatening notification. Instagram has technology that can identify content that has been previously removed, and remove it instantly if it reappears on the platform.

“Your account may be deleted,” the notification said. “Your post goes against our community guidelines.”

Instagram flagging and censoring students for nude or sexual content is not a singular experience. UVic art students have long used Instagram to share their art. During the pandemic, the Visual Arts Student Association has begun hosting virtual studio visits on their Instagram that showcase student work and work processes.

Social media can be a vibrant place for inspiration, collaboration, and interaction for young and emerging artists. But art that deals with nudity and sexuality is held to a different standard.

Instagram policies make ‘allowances’ for nudity in scenes of breastfeeding, acts of protest, photos of post-mastectomy scarring, “health-related situations,” and photographs of art. But the algorithms that automatically remove and warn users often can’t differentiate the context of art that dips into the realm of skin and sexuality.

Automated content moderation happens on a variety of levels: work might be taken down outright, while merely “inappropriate” work would be demoted and less likely to appear in users’ feeds. The lines between appropriate, inappropriate, and bannable content are not clearly defined. For artists that work with nudity or sexuality, every post on Instagram is made under the metaphorical eyes of the algorithms that police and enforce Instagram’s policy on nudity and sexual content.

Bunrayong is a first-year visual arts and art history student that’s exploring conceptual and performance art. She’s kept an art Instagram since highschool so that she can look at her development over the years. There are nude studies in her feed. But now that her work has moved from drawing towards exploring the nude body in photography, she doesn’t know where to put her art. Bunrayong said that her experience with Instagram is not going to discourage her exploring nudity in art.

Second-year student Zaida Gerritson has been in art school since she was five. Formally trained in oils and acrylic, Gerritson is using her time at UVic to explore performance art and film photography. Her art often references mental health. For Gerritson, her bipolar disorder is intimately connected to the physical body, and she wants her work to reflect that.

Gerritson has only been on Instagram for a year — she is used to having her work in galleries.

“I’m not getting the feedback that I normally get from in-person right now, so I’m kind of struggling,” said Gerritson, noting how Instagram has taken an increasingly prominent place in her art practice during the pandemic. “[With Instagram,] we’re able to see each other’s work, and know that we’re not creating in a void.”

It’s also a frustrating, limiting space. After hearing about her peers’ negative experiences, she censors what she puts on Instagram.

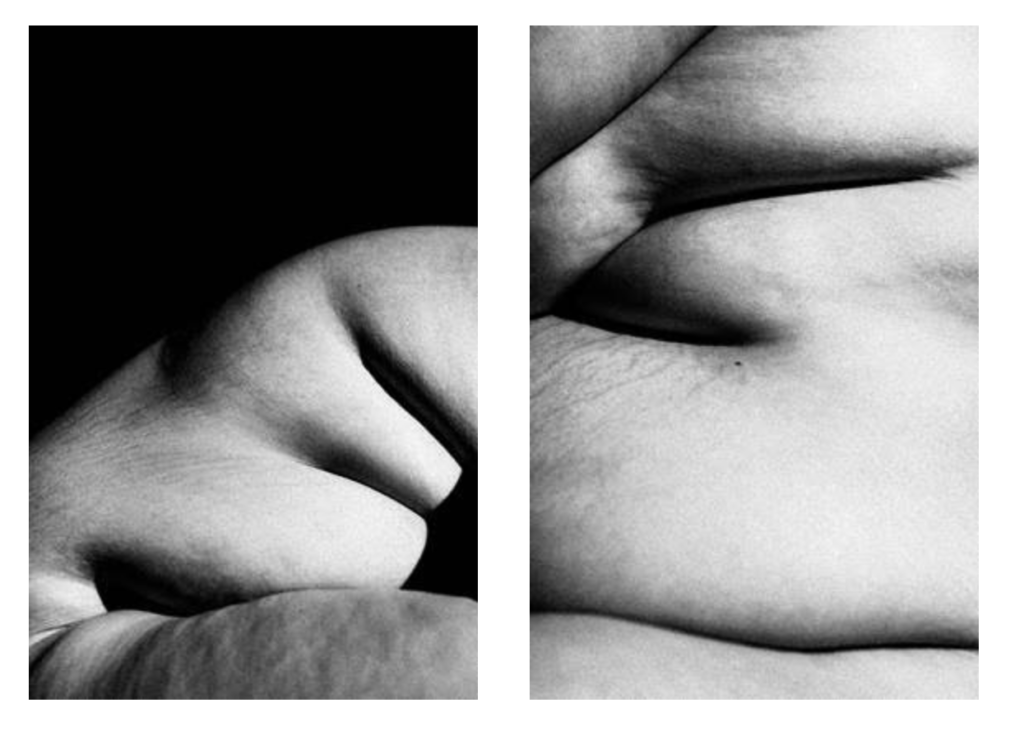

If not for Instagram, Gerritson’s latest work — a performative, gestural piece entitled “Herself” where she depicts her struggle with bipolar disorder — would’ve been entirely unclothed.

For Juliana Sech, a third-year visual arts student, the nude body is sacred. It’s also what she considers her primary artistic tool: the mediums are merely various expressions that she works with to explore sexuality, gender norms, and the blurred lines between sexuality and sensuality.

“There’s this weird thing where the body is seen as purely sexual, instead of it just being natural,” said Sech. “Even if it is shown as sexual, there [should be] no problem with it. It’s just an aspect of life.”

Sech sees the power of Instagram in moving art away from museums and galleries. She estimates that 85 per cent of her work would violate Instagram’s community guidelines, and has received warnings in the past

“The restrictions on Instagram are very unclear, and even if you follow them, they can still delete your content,” Sech said. “It’s hard to know what is appropriate and what isn’t.”

Sech says that Instagram’s selective censorship is hurting emerging artists, and is also limiting authentic expression. “In mainstream media and these music videos that you’re watching — it’s usually a specific body type,” said Sech. “There’s other art that shows more different kind of bodies, maybe with hair.”

Instagram’s algorithms also perpetuate norms about what bodies are seen as acceptable. Thin, white, conventionally ‘attractive,’ scantily-clad women are pushed forwards by the algorithm, while other body types are automatically removed. As reported by the Guardian, lithe algorithms often mirror the racial and sexist biases of our society. Censorship isn’t being applied equally across the board — celebrities can post from strip clubs, but a smaller account posting similar content would be taken down.

Olivia Zappone is perhaps best known for her photography, but she’s also an occasional poet, videographer, and bookmaker that explores intimacy through her work. The fourth-year visual arts student built her fashion portfolio by collaborating and networking with others on Instagram.

“You want to parallel what you’re working on in the real world with what you’re expressing online,” said Zappone. “[Instagram] is very limiting when it comes to conversations about sexuality or conversations about intimacy.”

Zappone has tested the algorithm with a photoshoot where she depicted a nude body, distorted and filtered behind water-filled vases. The post got removed.

“There was a nipple that was kinda wonky in the water,” said Zappone, laughing self-effacingly. In the past, she says her work would’ve been fine on Instagram, after scratching out or blurring the required body parts, but Instagram no longer permits this.

She’s considering moving more of her work off that platform, but Zappone recognizes that she’s more established and is now working in mediums that don’t require Instagram as much.

According to Instagram’s Community Standards, they allow photographs of paintings, sculptures, and other art that depicts nude figures. This also applies to digitally-created content with nudity unless it is posted for educational, humorous, or satirical purposes.

They also restrict some images of female breasts if they include the nipple, but we allow photos of women actively engaged in breastfeeding or showing breasts with post-mastectomy scarring.

“We want Instagram to be a place where people can express themselves, but we also have a responsibility to keep people safe. We try to write policies that adequately balance freedom of expression and safety, but doing this for a community of a billion people from all corners of the world will always be challenging,”said the Facebook company spokesperson.

For Zappone, her feelings towards the app have soured. “It seems to be so fragile,” said Zappone. “Overnight, something would change and it makes the whole thing shaky and you can’t even communicate with people anymore.”