Personal experiences shouldn’t need to be dictated by labels

When it comes to gender identity, words matter. Often, preventing acts of discrimination starts with learning these words. The right words can signify respect, recognition, and affirmation, while the wrong words can cause confusion, distance, or even animosity.

But words are limited. Language is limited. In many cases, language is inadequate at expressing the nuance and granularity of human relationships.

Rob Brooks is a third-year engineering student who spoke with the Martlet about his experiences being queer, and his frustrations with people’s attempts to label him. Brooks grew up in a small conservative town in the Cowichan Valley, which he described as “black-and-white,” and “boy-girl-oriented.”

“My experience with gender expression was I was born male, [and] filled out the role of a boy,” said Brooks. “So socially, I didn’t experience much fluidity. But since I was a child, I was always balancing a lot of feminine aspects and masculine aspects.”

Brooks told the Martlet he never really questioned his gender, nor felt the need to assign himself a label. He always felt comfortable with who he was.

“My first relationship with a guy was something that happened organically. It wasn’t something I was seeking, or even aware I was interested in or capable of. It just presented itself, and was really positive.”

He explained that as soon as the people in his life began to demand labels from him — trying to determine whether he was gay, bisexual, agender, or otherwise — he experienced frustration with his loved ones, and friction in his relationship.

“The people in my life’s response to it was like grasping at straws, seeking labels and understanding for themselves, almost in what I perceived to be a selfish manner,” he said. “They needed to make sense of my experiences so that they could confirm what they had always thought about me.”

Brooks said he sometimes identified as queer, an umbrella term for LGBTQ2+ people. While many accept queer as the best cover-all term, the word’s derogatory roots have precluded its mainstream acceptance. Moreover, the term lacks specificity. While Brooks admitted the word has sometimes helped him connect with a shared community, he still felt it seemed inadequate at characterising the extent of his subjective experience.

Brooks agreed that he felt more comfortable being described as gender apathetic. Gender apathy describes people who do not identify with any predefined gender identity, or prefer not to be classified. Gender apathetic people may also be pronoun indifferent, or pronoun apathetic.

The word is similar to cassgender, inersgender, apagender, avisgender, greygender, agender, and many other related terms. But to anxiously probe for the most suitable word would be to fall into the same trap which made Brooks so weary in the first place.

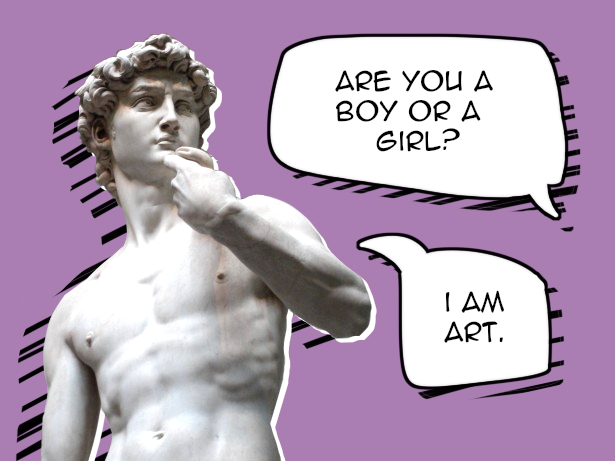

In other words, no label might be better than any one label. This rejection of classification may sound strange; humans love to label things. We like to tuck everything into a convenient box and file it away. We spend so much time in class pounding nomenclature into our brains that we instinctively seek to subordinate everything else into terminology. But maybe some things shouldn’t need labels.

“I would firmly say I’m gender apathetic,” said Brooks. “Especially because I’ve never questioned my gender identity to the point of needing answers.”

We may be living in a post-coming out age. Non-heteronormative relationships and gender fluidity are becoming entrenched within the cultural norm. Some people no longer feel the need to publicize themselves.

Some might worry that obfuscating gender identities will weaken LGBTQ2+ political power. Others might counter that being openly queer inherently challenges the heteronormative hegemony. Existing openly with your identity — labelled or not — creates space that may have been otherwise devoid of queerness.

Moreover, the custom of identifying things through labels has created many avenues through which those labels can be used as weapons. Think of the arbitrary designation of races, social classes, and religious denominations which were constructed to marginalize and oppress certain peoples.

Often, our subjectivity can’t adequately be categorized, and we shouldn’t be bothered by that. Our evolving views of sex and gender are challenging existing sociolinguistic categories. For many, gender labels can feel as restricting as having to live within the limits of the western gender binary.

“I don’t think current experiences should be dictated by the labels we once identified with,” said Brookes.

In the end, gender is a story, and stories derive their meaning from a culture. For many, gender labels can be invaluable in helping to affirm their individuality. But for others, taking on one of these labels can be like living someone else’s story. Even worse: if that story is yet to be written, it can be puzzling to know where you fit.

But when it comes to your life, you’re the author — and no one else can write it for you.