It’s one of the best tools we have to combat the overdose crisis — and training is easy

Photo by Ethan Barkley.

Earlier this year, I attended one of UVic’s monthly naloxone training sessions held in the Student Wellness building. The sessions are a harm-reduction resource to combat the ongoing overdose crisis.

Students and faculty members alike turned out for the session, which took a little over an hour. The nurses running the session didn’t assume any prior knowledge, and patiently explained how to identify different types of overdose, answered any questions we had, and then taught us how to administer naloxone via injection.

British Columbia first declared the overdose crisis a public health emergency in April 2016. Eight years later, more than 15 000 British Columbians have died as a result of toxic drug overdose. According to the most recent statistics published by the provincial government, from July 2024, deaths due to overdose are estimated to be 6.2 per day.

While 2024 has seen an overall decrease in toxic drug-related deaths compared to 2023 — which saw a record-breaking 2 572 — the number is still far too high. According to B.C. government statistics, 1 365 people have lost their lives this year as a result of toxic drug overdose.

Statistics like these can be difficult to visualize in human terms, and the prospect of solving a systemic problem like the overdose crisis can seem totally out of our hands as individuals. Implementing proactive, evidence-based policies like safe supply and decriminalization, safe use, and expanding treatment options are critical if we hope to stop this crisis. However, there are also ways we can help on a smaller scale, as individuals, to prevent toxic drug-related deaths in our communities.

One of these options is being trained to use naloxone.

Naloxone is known as an opioid antagonist. Put simply, it temporarily reverses an opioid overdose by targeting the receptors in our brain that opioids affect and binding to them instead, preventing the opioid from taking effect.

Naloxone only works on opioid overdoses — it does not prevent overdoses on substances of other kinds, like cocaine or methamphetamine — but it is completely safe to use, whether the recipient has an opioid in their system or not.

Opioids (substances like fentanyl, heroin, morphine, and codeine) are strongly correlated with the overdose crisis in B.C. Fentanyl was detected in 85 per cent of drug-related deaths in 2023, while other opioids were detected in around 20 per cent, according to B.C. statistics.

Whether you personally know people who use opioids or not, learning to use naloxone makes sense. Overdoses can take place in any setting, and being prepared in the moment to take action can be the difference between life and death. You should always call first responders if you suspect someone is overdosing, but it’s rarely clear in the moment how long someone has been overdosing for. Administering naloxone in situations like these can buy crucial time until emergency services can arrive.

At UVic, one of the ways you can learn to administer naloxone is through on-campus training workshops, which are run about once a month by the UVSS in partnership with the Student Wellness Centre.

Another option is to book a private training session with a UVic nurse.

The training session I attended was the former option. Prior to the workshop, I was worried I would have to practice giving naloxone to a real person — one of the other attendees, or a nurse. Thankfully, this wasn’t the case. Nurses instead had us practice giving injections to a DIVA Cup, which is supposed to feel similar to giving a real injection.

This made the training significantly less stressful than I expected, though I do wish they had advertised that fact up front. Students like myself, who are made somewhat squeamish by needles, might be more inclined to attend if they knew they did not have to give another person an injection as part of the workshop.

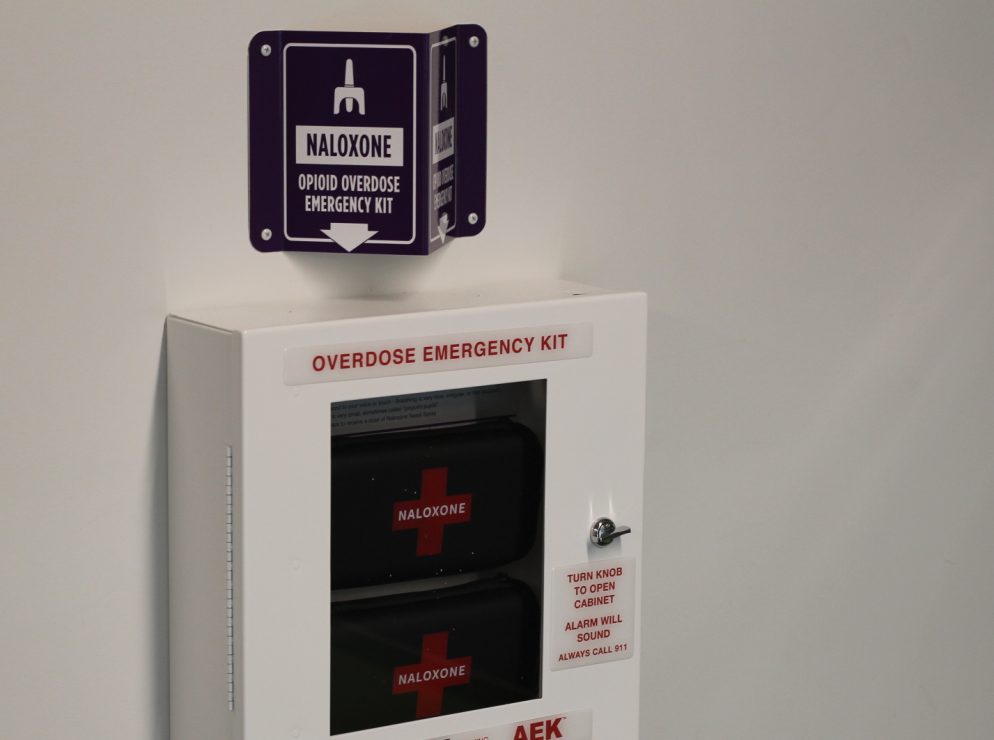

At the end of the training session, we all received a free naloxone kit. While these kits are available for free at two locations in the Student Union Building (SUB) — the Harm Reduction Centre (SUB B002) and the Campus Pharmacy — the hands-on training from UVic nurses on how to use naloxone kits made the procedure feel approachable.

Kennedy Halwa, a fourth year creative writing student at UVic, and Piper Elliot, a second year music education student, also took naloxone training sessions offered by UVSS and Student Wellness over the summer.

Halwa said she was motivated to take the training in part by the tragic death of Sidney McIntyre-Starko in January, as well as by a general sense that it was useful training to have.

“I wanted to make sure I had my naloxone training, so that should I ever be in that situation where I suspect someone is overdosing, then I can [do something],” she said.

Elliot told the Martlet about an experience they had in first year, where their bus driver stopped to help somebody who was overdosing at a stop. This experience was part of their reason for taking a naloxone training session.

“I don’t know if he had naloxone,” said Elliot, “but if I had some at that point I could have said, ‘Hey, I have [this].’”

The overdose crisis impacts everyone, but as students and members of the UVic community, we may find ourselves more frequently in situations where substances are being used — parties, clubs, and concerts, to name a few. As such, we need to be prepared in case we find ourselves in a situation where someone is overdosing. Free naloxone training workshops, like the one I attended, are an incredible resource which all members of the UVic community can benefit from.