The North American beaver.

They’re an icon of Canadian heritage, but for UVic sessional instructor Frances Backhouse, they’re a lot more valuable than their place on the nickel.

Frances Backhouse, a sessional instructor at UVic, will be launching her new book at the Copper Owl on Oct. 8. Photo provided.

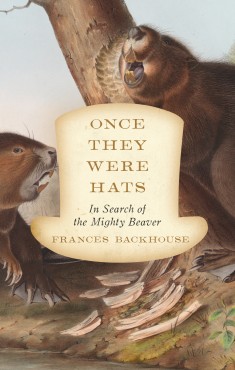

With the upcoming launch of her new book Once They Were Hats, Backhouse uses her passion of ecology to shine light on the critical role beavers play in the environment. She says their extinction as a species would affect the entire ecosystem and the organisms that depend on them.

“As I got into it, I was struck by their huge influence on the landscape,” says Backhouse. “I was amazed to find out that for millions of years they have been reshaping valleys and influencing the way watersheds move. I started to wonder what would happen to us if these animals disappeared. And for a moment in time, they almost did.”

With the arrival of settlers and start of the Fur Trade, the beaver population dropped from 60 million to 100 000 in only 300 years. The decline of these animals shifted much of Canada’s landscape from a thriving wetland to a brittle terrain.

But as droughts became a more serious issue during the Dirty Thirties, regulations were set for the trapping of beavers. Research cited in Backhouse’s book says a piece of land in Alberta’s Elk Island National Park produced nine times the amount of water after new regulations prompted the reintroduction of beavers.

Yet, while at the 2010 North American Fur Trade Auction in Toronto, Backhouse discovered a startling fact. The number of beavers being trapped presently actually exceeded the number of beavers killed during the peak of the Fur Trade. Backhouse says that this was her “watershed moment.” It was time to start caring more about these animals before history was repeated.

B.C. has experienced one of the warmest summers in history, with the threat of drought hanging over the heads of Victoria residents. Backhouse suggests looking to beavers as “environmental allies” for help as temperature rises and the land becomes drier.

Beavers do much more than chew down trees and flood urban roads. The dams they build trap flowing streams into pools of still water. This causes the water table to rise over an area, which supports the growth of habitual wetlands. Backhouse says this process of diversifying the ecosystem will help reduce the chances of drought.

So how can we coexist with animals that are often seen as pests? Backhouse says we need to “learn to adapt to them.” Building fences around park trees is effective against beavers while ensuring the plants still have ample room to grow.

Newly invented humane technology also holds great promise against these animals. The Beaver Baffler is a small pipe that runs through a dam and syphons off water without the beaver’s knowledge. People can set the water level to control potential flooding and the beavers are able to stay where they are.

Backhouse invites guests to transform how they think about these furry critters, from buck toothed pests to environmental friends, tonight at 7 p.m. downtown at the Copper Owl.