Star cluster discovered by UVic faculty and alumni sheds light on the beginnings of our galaxy

University of Victoria faculty and alumni played key roles in last year’s monumental discovery of the globular star cluster C19. Dr. Kim Venn, UVic professor of physics and astronomy and co-lead of the research team that made the discovery, calls the cluster a “missing link” in the examination of early galaxy formation.

Venn explained that some timeline estimation was previously required when talking about events that happened after the Big Bang, like when the first stars formed. Following the discovery of this oldest structure in our universe, however, those long-standing scientific understandings of the early universe are being challenged.

Venn’s team’s direct and crucial involvement in this discovery is aspirational for UVic students in the sciences, and a source of pride for the UVic community alike.

“We’re usually at our desks, in our offices. Unfortunately, it doesn’t happen like in the movie Don’t Look Up,” said Venn, referring to the moment of C19’s discovery.

“It was really during a group meeting and we were convincing ourselves we hadn’t missed something,” she said

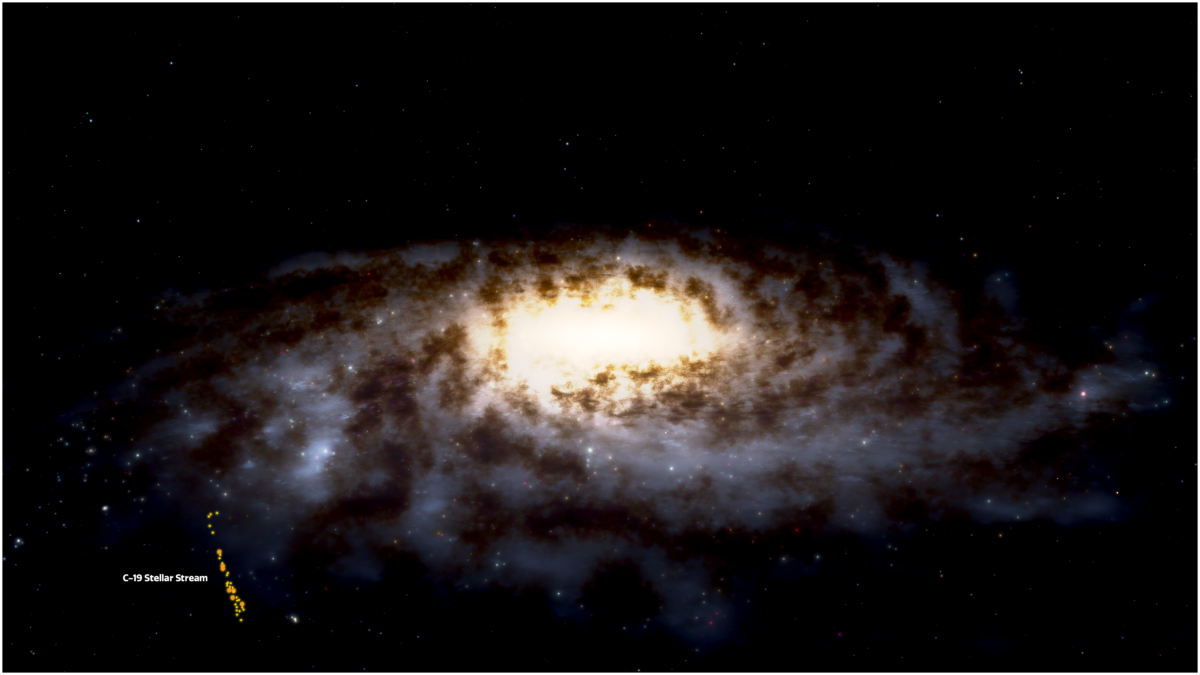

C19 is an ancient globular star cluster in the Milky Way galaxy. Its scientific importance centers around its metallic properties. The metallicity of C19 is two times lower than any other star cluster, or 0.05 per cent the metallicity of the sun, meaning that C19 is the most metal-poor (or lacking in heavy elements) of any such existing galactic systems. The discovery of the ruins of this cluster means that metal-poor star clusters do exist, and that it is possible to study these ancient structures within our galaxy as fossils, reframing the age-old theories of astronomers past that star clusters lacking so significantly in metals could not exist.

Venn took the initial observations of the globular cluster nearly a year ago, in January of 2021. A colleague was working on Maunakea, Hawaii on the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope, searching the Galactic halo for metal-poor stars while Venn observed remotely from her office due to COVID-19.

“I looked at [the observations] immediately. I knew they were interesting, but I didn’t know they were going to be a discovery,” said Venn. It was the end of March or beginning of April before she was able to present her findings to her colleagues — chemical footprints that were indicative of a globular cluster as opposed to the more general results that are often seen for dwarf galaxies.

“I was able to convince my colleagues — because all scientists are highly skeptical — that we have the most metal-poor globular cluster ever discovered, and this makes it the oldest structure ever found in our [galaxy],” said Venn. “We all kind of got excited at the same time.”

UVic’s research team consists of scientists and engineers at the National Research Council of Canada’s Herzberg Astronomy and Astrophysics Research Centre, as well as astrophysicists from the Pristine collaboration, who collaborate from Toronto, Europe, and Russia. So, why was this discovery of importance to UVic students? Because members of the UVic’s student body also played crucial roles in C19’s discovery.

Venn highlights the involvement of one former PhD student in her research group. She explains that his thesis was focused on the kind of data analysis necessary for C19’s discovery. His development of rapid analysis pipelines allowed for the data that Venn’s team collected in January to turn up results “right away.”

It’s not only PhD candidates playing important roles in Dr. Venn’s research teams, though.

“We have graduate students, undergraduate students, and post-docs who are all involved in the team at UVic,” said Venn. Students at various standings in their post-secondary careers perform calculations of the orbits, orbital dynamics, stellar parameters, and errors.

Venn has an important message for science students at UVic.

“What I hope is that UVic students would realize that they are capable of being involved in discoveries like this, that we have the expertise, that we have the facilities, and you don’t have to be in an observatory to do this,” said Venn.

“You don’t have to wait until you’re a full professor to make discoveries like this. You can be involved in this on the ground level, in astronomy.”

Venn tied her statement up with the assertion that although recent discoveries have been led by professors, they are often driven or even generated by students who are doing this work. Venn’s team is, then, not only a brilliant example of UVic excellence, but also an inspiring collective of students and astronomers who shine like something of a North Star for aspiring student scientists.