It’s time to rethink the way we challenge oppressive language

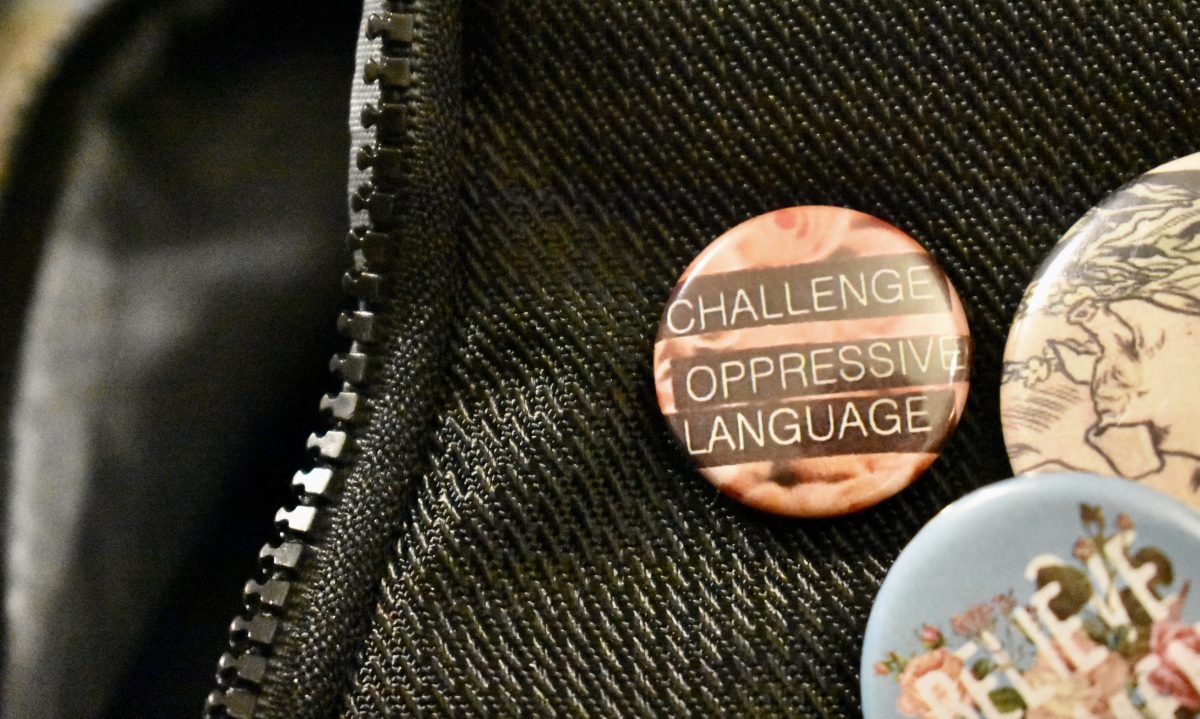

Photo by Sydney Lobe.

Recently, I was rifling through a basket of free pins at the Anti-Violence Project’s office in the basement of the SUB. I settled on a button that says “Challenge Oppressive Language.”

As I slid the button onto my backpack, I thought about its call to action. For me, the commitment to challenging oppressive language is twofold; it means both aiming not to hurt others with my words and, because it is something I care about, holding those who care about me accountable to a non-oppressive vocabulary as well.

I am thinking in this article, which will appear in the sex and gender issue, particularly about language that is oppressive to non-men — words like b*tch, sl*t, wh*re, etc. This is not to exclude other oppressive language from the conversation, but rather because it’s a relevant focal point for a lofty issue.

Language use has real, tangible consequences as it has historically been used to manipulate, control, hurt, and oppress marginalized groups. And on an individual basis, we have all, at one point or another, been hurt by name-calling or directed insults.There is so much pain that lives in etymological history; language has always held the capacity to be a vehicle for oppression. Thus, stakes in our fight for gender equality are as high on the page and on our tongues as they are in the streets, in our homes, and our workplaces.

Usually, when I overhear people speaking up to resist an oppressive word or phrase, it sounds like “you can’t say that,” or “you shouldn’t use that word,” and it’s often brushed off with a quick apology, or worse, met with a laugh or an eyeroll. In my experience, the next steps are usually rinse and repeat.

One of the reasons I suppose this happens is because words like b*tch are so common in our lexicon, that it feels to users like the words’ frequency of use correlates to the degree of harm they are capable of causing. Of course, this isn’t true.

I often wonder: why does my attempt at challenging oppressive language, and the attempts of those around me, feel like an unsatisfying, even Sisyphean task? Why doesn’t it stick?

I had a conversation with my friend recently about interpersonal boundary-setting. Her therapist told her that a boundary with a friend or partner is not functional without a consequence to breaking that boundary.

I think this applies in the context of challenging oppressive language, too.

“Don’t say that,” or worse, “you can’t/shouldn’t say that,” are the linguistic equivalent of a parent telling their child to turn off the television without giving a reason or a consequence for what might happen if they don’t.

The result is bad for both the policing force and the policed. The policed party feels scolded or maybe a sense of shame or misdirected anger at the other party — not for their request, but for being told what to do. On the other hand, the policing force feels unheard, embarrassed, even potentially ostracized when they are not taken seriously.

If we’re thinking about what my friend said — that consequences are essential when instating boundaries — that might look like saying “we can’t be friends if you keep saying that word.”

But here we are again, in a lose-lose situation. The person using harmful language may feel taken aback or judged, and has the opportunity to weaponize this severe boundary as evidence of uptightness. Also, backlash against what we are told we can’t do is natural. A kind of alluring, forbidden novelty is thus introduced to the word when it feels off-limits, and so the slur in question remains in use — either by reason of carelessness, rebellion, or novel appeal.

And on the other hand, the boundary-setter in this situation is potentially losing a friend because they initiated such a high-stakes ultimatum.

It is exhausting to be the b*tch police.

So, where do we go from here?

To me, the word “challenge” in the phrase “challenge oppressive language” brings to mind the image of two lancers in their ready positions. Ready for a challenge, indeed.

I have been thinking about what it would look like to reframe challenging oppressive language by speaking up in a way that is productive and forward moving, rather than in a way that places us and our loved ones on opposing sides of a confrontation.

Instead of a discouraging aside in conversation such as “don’t say that,” what might it look like to instead find an appropriate time to put the onus for change on your friend or loved one, as opposed to letting the burden of policing fall on you?

For me, a more productive solution is to be honest about the emotional impact of the oppressive language used by those I care about, then leaving the responsibility of what to do next to them.

“The fact that X is a part of your vocabulary makes me feel uncomfortable around you,” or

“When, as my friend, you say a word that has been used to hurt people like me, it embarrasses me,” are a couple of examples of what I think is a happy medium between firm chastisements with no real consequences and high-stakes consequences that don’t serve any parties in a relationship.

The approach is also a litmus test for whether the people in your life can value and respect your feelings. I hope that any change that this might facilitate would be more enduring too because it’s coming from an independent choice made from an informed position, not a prescriptive demand.

In order to work together, we have to reach a more vulnerable place of negotiation. In a perfect world this means a bid for empathy, met with willingness to try to understand.

As far as I’m concerned, there is no easy solution, except to listen to each other when we talk about what hurts, in any facet of life, and make an individual effort to eradicate oppressive language from our vocabularies — whether your loved ones have to tell you to or not.

And to my fellow b*tch police, don’t be discouraged; every evolution is incremental.